The easiest way to identify our house on Hendrie Blvd. in the ‘60s was to look for the enormous ham radio rig on the roof. It was like the house wore a silver crown of boxes and wires. Three parallel antenna rods spanned the length of the roof. Occasionally you might see them rotate as my father redirected them for the strongest possible signal.

“What does CQ stand for?” I asked. “It doesn’t stand for anything,” he answered. “It means ‘Seek you.‘”

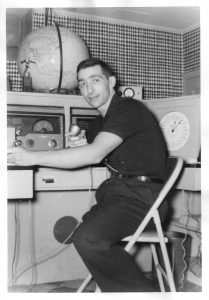

The antenna was controlled remotely from the basement, where my father had set up a radio communications center. It started out bare-bones, as home offices go: bare walls adorned with taped cards and certificates, exposed heating ducts, linoleum flooring, a used desk, a folding chair. (Later, he upgraded with checkered wallpaper, an acoustic ceiling, and a custom-built gray wooden console, like a Navy ship.) Where my father didn’t skimp was the equipment: an array of stacked components, their faces plastered with meters, gauges, switches, buttons, jacks, and dials. A world clock. A telegraph key he didn’t use much, although he was fluent in Morse code. And, in the center of the desk, a microphone.

“CQ,” my father intoned. “CQ, CQ. This is W8YIN, William Eight Yokohama Item Nancy, out of Detroit, Michigan.” Detroit was close enough; nobody knew where Huntington Woods was. “CQ, CQ.” “What does CQ stand for?” I asked. “It doesn’t stand for anything,” he answered. “It means ‘Seek you.’ I’m searching for someone to talk to.”

It was his passion. After he graduated high school in 1943, he joined the Navy. He learned about radio at Naval ROTC in Marquette, and later served in the Pacific as a shipboard communications officer. He arrived too late to see action, but participated in “mopping-up” operations. Now, evenings and weekends, he’d retire to his radio room, switch on the components with a hum and a crackle, and call out to other radio buffs around the world.

When he made contact, they’d talk about their work and their families. They’d talk about where they lived and what it was like there since the war. Mostly they’d talk about their rigs, how good (or bad) the signal was, and what new equipment they had or wanted. They’d just talk.

After each call, my father would meticulously enter the details in his log. Later, he’d send them a CQ card with his call letters and location. A few weeks later, we’d get their cards in the mail, with exotic stamps that I’d add to my collection.

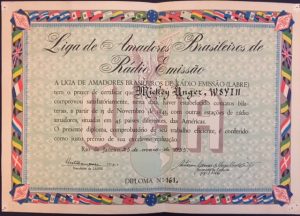

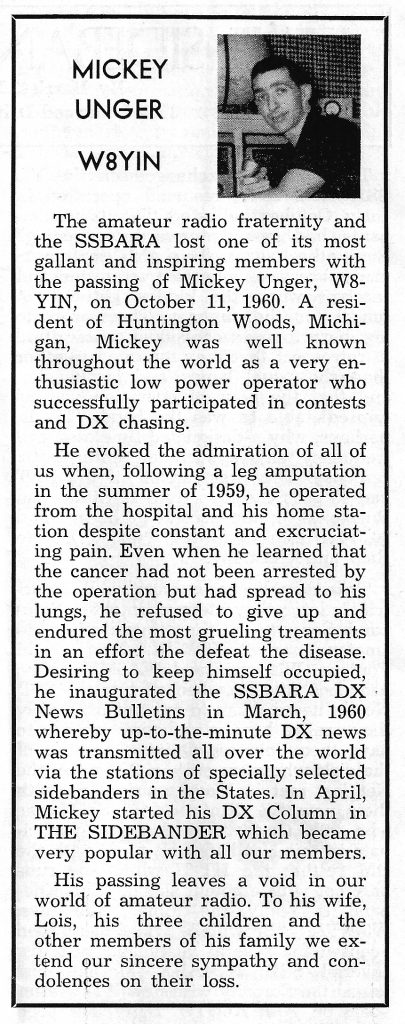

During competitions, he’d spend the whole weekend at his radio console, racking up call after call, country after country. I inherited a thick envelope of awards and certificates from all over the world. Worked All Europe. Worked All Africa. Worked all Pacific. Worked all Americas. Worked all Continents. Awards in French, German, Spanish, and Portuguese. One hundred countries. All forty zones of the world. Fifty districts in the British Empire. Letters of commendation for disaster assistance.

Starting when I was about six, he’d occasionally sit me down in front of the mic. “This is Arthur from Melbourne, Australia,” he’d say, spinning the globe and pointing. “Say hi.” I would dutifully comply, but after that, I never knew what to say. I didn’t understand that what I said wasn’t the point. I could have talked about the Detroit Tigers or sung a verse of “Doggie in the Window” or “Hound Dog.” (I liked songs about dogs.) The point was that I was talking to someone halfway around the world—from Melbourne, Australia, for crying out loud.

In retrospect, I wish I’d shown more interest, gotten more involved. It could have sparked a fascination with radio or a career in electronics. Mostly, it would have been a way to spend quality time with my father. But I was just a kid. I didn’t realize that time was so precious.

I only wish he had lived to see modern technology, to see personal computers and smartphones and the Internet. My mom, as she aged, stuck to phone calls and letters; she refused to learn to use email even though it would have brought her in touch with her grandchildren. I suspect my father would have been an early adopter of all of them. I suspect he would have loved Facebook, not to mention Retrospect. Because what was ham radio if not early social media?

CQ, Daddy. I seek you. I seek you.

Read Mickey Unger’s poignant essay on fatherhood, Upon Reaching the Age of Three, on Retrospect.

John Unger Zussman is a creative and corporate storyteller and a co-founder of Retrospect.

John, how fascinating to learn about your father and his passion for ham radio. I love how he would sit you down to talk to someone in Australia or other exotic places! It does really sound like early social media. The obituary in Sidebander Magazine was so touching it made me cry. Wonderful that he was so loved by the amateur radio community. Thank you so much for sharing.

Suzy, thanks for your kind words and for being moved by my father’s passion. He left me a very special legacy and I’m honored to share it with you.

Wow, John, I had no idea about your dad. How fascinating. The obituary you provide is very moving and a great tribute for your long-gone father’s enthusiasm and, yes, heroism, in the face of a terrible prognosis, to continue to do what he loved. You describe it with precision and help us all understand the thrill he must have felt in those long-ago years to communicate with someone worlds away. Your final line brought me to tears. I was thinking of my own father just hours ago, who hasn’t been gone nearly as long (a mere 28 years), but is also truly loved and missed. You touched a nerve.

Betsy, I hadn’t thought of my father as heroic but the way you put it, it makes perfect sense. Thank you for giving me a new way to think about him!

Tugs at my heart again today, as I mourn another father figure…known to both of us, but particularly dear to me. Though Dude was quite old, his death was unexpected; indeed, I was making plans to visit him next summer. Loss is loss and is never easy, no matter when it comes.

Thanks, Betsy. I’m sorry for your loss, but happy we could both partake of Dude’s passion for operetta.

John, what a wonderful story and tribute to your father. I love the detail about the ham equipment and environment, and what it meant to you and him. The obituary and your ending touched my heart. This has special meaning because my uncle, now deceased, was a long-time ham radio operator, but I didn’t know that much about it, so your story educated me. I have been told that my uncle was one of the youngest people to obtain his license in suburban New York, at the age of 14. This would have been in about 1936!

Marian, I’m pleased that my story educated you because writing it educated me as well! Your uncle was just a few years older than my father, so I wonder if they ever communicated? In any case, I’m glad my father’s story touched you.

John, so glad I caught up with this as a Past Story.

It gave me a fascinating peek into the ham radio world and its passionate amateur operators, but of course it’s really about the loving relationship between a father and a son.

Thanks so much, Dana. I love stories like that, that seem to be about one thing but are really about another. Glad you appreciated it.