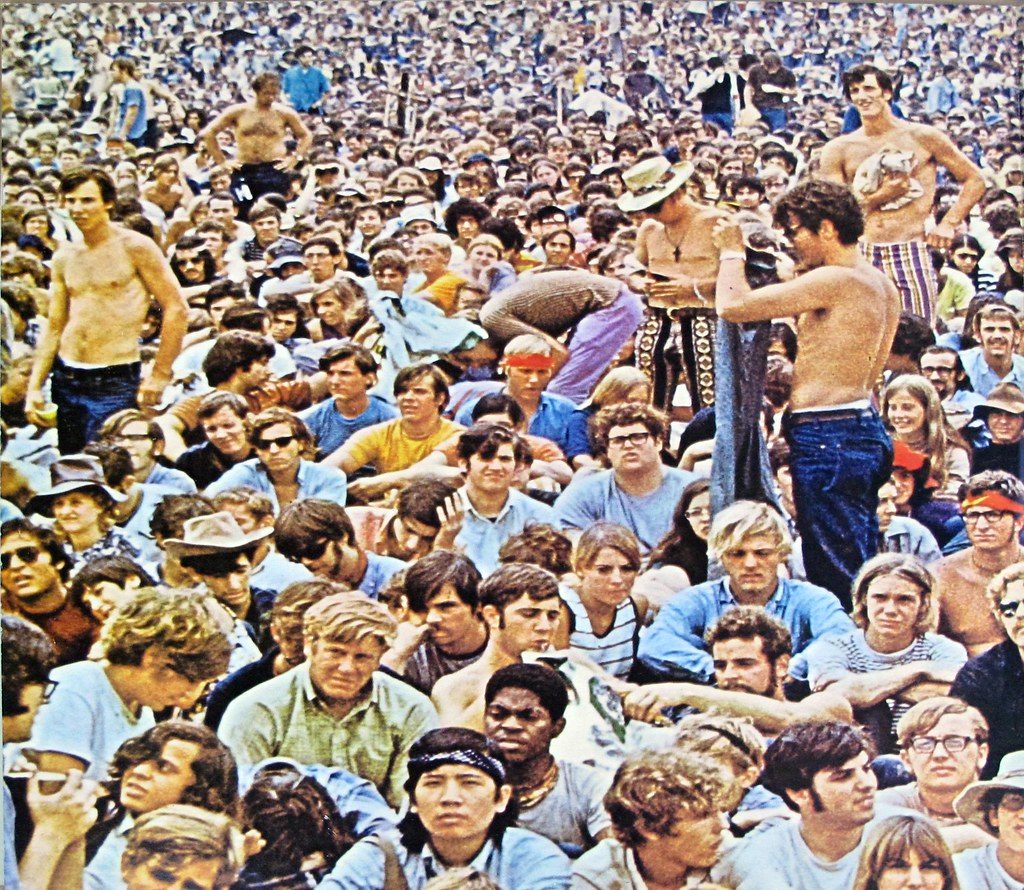

Woodstock was another huge moment of 1969 that happened when my husband and I were on our grand tour of Europe, Greece, and Israel. While almost a half-million “hippies” formed a community of peace, love, and music on Max Yasger’s farm, we were tooling around Israel blissfully unaware it was happening.

Seeing the documentary movie version the summer of 1970 shaped my Woodstock experience.

Thus, it was seeing the documentary movie version the summer of 1970 that shaped my Woodstock experience. We were visiting my family in the Detroit area and my parents were out for the evening. While we were celebrating our second anniversary and I was a high school English teacher and my husband a medical school student, we still felt young and carefree. After all, we were many years away from being thirty, the age at which people were no longer to be trusted in those days.

My younger college student brothers were heavily into pot back then. Amazingly, my parents had no idea this was happening. In fact, my mother found cigarette rolling paper and what she thought was tobacco under a sofa cushion and was upset that my brothers were smoking cigarettes. She asked me why they would choose to roll their own rather than just buy them in the store. “I have no idea, Mom.”

The four of us determined that Woodstock was an experience best seen stoned, and we proceeded to get high before departing for the movie. It was playing at one of those old, ornate movie palaces downtown, so we piled into my brother’s car and drove to the theater, erratically changing lanes on the expressway and laughing hysterically while the radio blasted. As my brothers predicted, the movie blew our minds. Actually, I don’t remember it all that well except for euphoria of sharing the experience.

By the time we returned to my parents’ apartment, the magic had worn off. We were confronted with the mess we had left and by the need to air the place out to remove the smell of marijuana, although I doubt my parents would have know what that strange smell was. Despite the fact that I would be a mother by the following summer, I felt cool and carefree that night.

My generation was haunted by political assassinations, upheaval over civil and women’s rights, and the threat of being drafted to fight an unjust war in Vietnam. Songs like Freedom by Richie Havens, I Feel Like I’m Fixing to Die Rag by Country Joe and the Fish, We’re Not Going to Take It by The Who, and Jimi Hendrix’s amazing rendition of The Star-Spangled Banner spoke to our passion and anger.

My generation was haunted by political assassinations, upheaval over civil and women’s rights, and the threat of being drafted to fight an unjust war in Vietnam. Songs like Freedom by Richie Havens, I Feel Like I’m Fixing to Die Rag by Country Joe and the Fish, We’re Not Going to Take It by The Who, and Jimi Hendrix’s amazing rendition of The Star-Spangled Banner spoke to our passion and anger.

A recent PBS American Experience Documentary, Woodstock, Three Days That Defined a Generation, brought the experience of being young and politically angry in 1969 back. What really struck me, 50 years after Woodstock, was the story of Max Yasgur, the man who agreed to allow the festival to take place on his farm. He was a conservative Republican who supported the war in Vietnam but also wanted to close the generation gap and believed older Americans should try to understand the younger generation’s views. When food concessions ran out of goods, he and the local citizens donated food and water to ensure that the kids attending the concert were fed and cared for. Yasgur was a very different Republican from today’s breed. His son described him as an individualist governed by his principles and belief in freedom of expression rather than by profit or greed.

He told the town board of Bethel before the festival:

“I hear you are considering changing the zoning law to prevent the festival. I hear you don’t like the look of the kids who are working at the site. I hear you don’t like their lifestyle. I hear you don’t like they are against the war and that they say so very loudly. . . I don’t particularly like the looks of some of those kids either. I don’t particularly like their lifestyle, especially the drugs and free love. And I don’t like what some of them are saying about our government. However, if I know my American history, tens of thousands of Americans in uniform gave their lives in war after war just so those kids would have the freedom to do exactly what they are doing. That’s what this country is all about and I am not going to let you throw them out of our town just because you don’t like their dress or their hair or the way they live or what they believe. This is America and they are going to have their festival.”

On August 17, 1968, Yasgur addressed the crowd at Woodstock, saying:

“I’m a farmer. I don’t know how to speak to twenty people at one time, let alone a crowd like this. But I think you people have proven something to the world… This is the largest group of people ever assembled in one place. We have had no idea that there would be this size group, and because of that, you’ve had quite a few inconveniences as far as water, food, and so forth… You’ve proven to the world is that a half a million kids – and I call you kids because I have children that are older than you – a half million young people can get together and have three days of fun and music and have nothing but fun and music, and I God bless you for it!”

Can you imagine a man like Yasgur saying that in 2019? That was the true magic of Woodstock.

I invite you to read my book Terribly Strange and Wonderfully Real and join my Facebook community.

Boomer. Educator. Advocate. Eclectic topics: grandkids, special needs, values, aging, loss, & whatever. Author: Terribly Strange and Wonderfully Real.

I love (though am slightly terrified by) the image of you, your husband and brothers driving downtown, stoned, changing lanes with reckless abandon. What movie theater was the documentary playing at (asks this fellow Detroiter)? I think I had a similar experience with my older, much straighter brother when Fantasia was re-released. We might have been the only two in the theater NOT stoned (at least I knew what was going on with all the giddy people in the audience; my brother was clueless. I think this was 1972, just after he returned from two years in Israel, before we each returned to our respective schools in September).

Interesting info about Max Yasgur. I didn’t know that about him. I have the PBS taped, but have only started watching the beginning of it. Been too busy here. Thanks for the insights.

Betsy, I can’t remember the name of the theater. It was one of those old, ornate palaces and I know it was in downtown Detroit because we took that unbelievably dangerous ride on the expressway (without seatbelts in those days). I remember Fantasia being really bewildering as a kid and was probably more appreciative when I saw it the next time. I probably took my kids to see it because we saw every Disney release. Wonder what my grandkids would make of it? I think you will enjoy the PSD show.

Laurie, this is a great example of tolerance from Max Yasgur. Makes you long for that time … Love the experience of seeing the documentary stoned.

Marian, I do long for some aspects of that era. While I hated Nixon, mourned MLK and RFK, and opposed the war that divided us, I did feel some of the peace and love that Woodstock represented. Now, most days I feel despair. Never thought our country could be more divided than it was in 1969, but here we are.

Laurie, I love this story, it made me laugh out loud multiple times. Your clueless parents asking you why your brothers rolled their own cigarettes, your wild ride to the movie theatre, your admission that you don’t remember the movie all that well, just the euphoria of sharing the experience. Perfect! And thanks for sharing Max Yasgur’s words to the town board and to the festival crowd – he sounds like an amazing guy, and you’re right, that wouldn’t happen in 2019, unfortunately.

Suzy, not only do I wonder how 50 years could have passed so quickly, but I am so sad that even those turbulent times seem kinder in retrospect that where we are today. That’s why Max Yasgur’s words surprised me. Thankfully, there was no twitter for Nixon back then. I never thought I would see our country more divided, but here we are.

If only there were Republicans like Max Yasgur today.

Sigh. I remember when folks like that were plentiful. I’m sure you do too.