Carson McCullers, author of “The Heart is a Lonely Hunter.”

I’ve been an avid reader most of my life, and the authors I return to most often are women. This is why: Women are in general more fascinated by the vagaries of human relationships than men, more focused on the details and textures of life.

I like male writers, too. Dostoyevsky’s 'Crime and Punishment' and Melville’s 'Moby-Dick' are huge favorites, and John Steinbeck's 'The Grapes of Wrath' is a thing of remarkable beauty. But overall, it’s the psychological depth of women authors -- their fascination with our inner lives -- that I find illuminating and essential.

Women are outsiders to a great degree: they nurture, they create comforts for husband and child, but historically they’ve been denied their own creative impulses. Being outsiders, they’re observers — better equipped to see the world from a broader, more nuanced perspective.

I’ve selected three women to celebrate, each of whom I’ve read for decades and each of whom I return to periodically – as if to an old friend.

Born in Virginia, Willa Cather moved as a young girl to the Nebraska prairie, where many of her novels take place.

My favorite author, Willa Cather, is remarkable for her great empathy – for the tender, overseeing regard she has for her characters. Whereas much of today’s fiction is defined by cool, ironic detachment or cynicism, those qualities are absent in Cather. It’s not that she’s mushy or sentimental, or that she spares her characters the harsh turns and disappointments of life — but rather that she reveals them with an open heart and insight. As if she were taking her character by the hand and gently presenting them to the reader.

She has bountiful gifts but Cather’s greatest, I think, is her ability to describe the landscape of the American Midwest and the Nebraska prairie: “I can remember exactly how the country looked to me as I walked beside my grandmother,” the narrator says in My Antonia, her most celebrated novel. “I felt motion in the landscape; in the fresh, easy-blowing morning wind, and in the earth itself, as if the shaggy grass were a loose hide, and underneath it herds of wild buffalo were galloping, galloping…”

Willa Cather in 1931. She wrote ‘Death Comes For the Archbishop,’ ‘Shadows on the Rock,’ ‘The Song of the Lark’ and ‘O Pioneers!’

Cather had an affinity for artists and loners, for young people starting out in life and the diminished elderly looking back in regret. Her heartbreaking short story “Paul’s Case,” about a stagestruck youth who leaves home with stolen money and briefly lives like a king, ends with one of the most devastating closing paragraphs in fiction. In my favorite of her books, Death Comes for the Archbishop, Cather illuminates the life of a French vicar establishing a Catholic church in 19th century New Mexico. There’s tenderness and understanding in the novel, such lack of judgment in her view of cultural differences and displacement.

Cather was herself an outsider. A lesbian at a time when secrecy and subterfuge were necessary for survival, she shared the last 39 years of her life with Edith Lewis, a magazine editor. The nature of their marriage was never revealed, and Cather arranged before her death in 1947 to have most of their correspondence destroyed.

Another passion is Carson McCullers, an outsider as well but often wickedly funny where Cather is measured and kind. I just revisited Carson McCullers’s Ballad of the Sad Café and found it sadder, more powerful than when I was in my thirties. It’s only 70 pages long – a novella — but it has the gravity and depth, the rich atmosphere and foreboding of an ancient Gothic fable. The central character, Amelia, is a mannish, 6-foot-2 woman who runs a general store and makes moonshine in her dreary Georgia town. Taciturn and friend to none, she astounds her fellow townspeople by taking a lover named Cousin Lymon, a gregarious dwarf hunchback.

In Ballad, McCullers has a stunning passage about “the lover and the beloved,” which encapsulates the central theme of her work: “A most mediocre person can be the object of a love which is wild, extravagant, and beautiful as the poison lilies of the swamp. A good man may be the stimulus for a love both violent and debased, or a jabbering madman may bring about in the soul of someone a tender and simple idyll.”

Julie Harris, Ethel Waters and Brandon DeWilde in the 1952 film version of “The Member of the Wedding.” It was a Broadway play in 1950, with the same wonderful cast.

McCullers wrote about the lonely and outcast — the people, like her tomboy Frankie Addams in The Member of the Wedding, who yearn to experience “the we of me.” There’s a scampish wit in many of her stories, and an exquisite facility for dialogue. Take Berenice Sadie Brown, Frankie’s plain-speaking nanny and housekeeper. Apart from Mark Twain, I can’t think of a white author who wrote better dialogue for African American characters.

Ask Berenice her opinion and she will give you an answer – whether you want to hear it or not. When Frankie wonders why she doesn’t marry T.T. Williams, the very proper gentleman who regularly takes her out to dinner, Berenice doesn’t mince words: “I respect him and regard him highly. But he don’t make me shiver none.”

Carson McCullers with her close friend Tennessee Williams. In the late 1940s or early ’50s, after she’d had three strokes.

McCullers was raised in Georgia and was twice married and divorced from Reeves McCullers, an alcoholic who committed suicide at 40. She did her best writing in her twenties, suffered a series of strokes and died at 50, in 1967. “Of all the Southern writers,” Gore Vidal said, “she is the most apt to endure.”

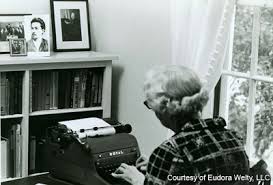

Another Southern writer I love, Eudora Welty, lacked the darker bent of Carson McCullers, but shared her appreciation for eccentricity and her ear for the intricacies of colloquial speech. Welty, who spent nearly all of her 92 years in Jackson, Mississippi, had a delicious, subtle humor and sometimes drew her story ideas from gossip overheard at the Jitney Jungle grocery store in Jackson.

She wrote five novels, including the Pulitzer Prize winner The Optimist’s Daughter, but her true métier was the short story. A Curtain of Green, her early collection of stories, was my introduction to Welty and I suggest it as a starting point. “Why I Live at P.O.,” a masterpiece of comic writing, is in the collection, as are “Old Mr. Marblehall” (whose wife “spent her life trying to escape from the parlor-like jaws of self consciousness”), and “A Worn Path,” about an old black woman trekking alone through deep piney woods to buy medicine for her grandson.

Welty once wrote that her “continuing passion” in writing fiction was “not to point the finger of judgment, but to part a curtain, that invisible shadow that falls between people.” She had the ability to enter a character’s mind, to capture their voice, their world, their joys and delusions.

In 2009, eight years after her death, I traveled to Jackson to soak up the Welty legacy and write a travel piece for the San Francisco Chronicle. The main branch of the Jackson Public library is named for her, the local theater has a playwriting competition in her name, and a bust of her head is the centerpiece in the town’s premier bookshop.

I visited the Welty home at 1119 Pinehurst Street, a Tudor Revival house where her family moved in 1925. Comfortable and unpretentious, the house is now a National Historical Landmark, operated by Welty’s niece Mary Alice White.

Welty wrote in her second-floor bedroom, which had windows facing both the street in front and her gardens in back.

Instead of a museum with the author’s history laid out in photographs and display boxes, the Welty House is designed to look exactly as it did during the 1980s. One gets the feeling that its owner – tall, graceful, with a voice like honeyed bourbon — has just stepped out to run errands. In the living room there’s the floral-print armchair where Welty sat each day. Next to it: a TV tray covered with a letter opener, stamps, paper clips, coasters and a box of Aunt Sally’s Pralines from New Orleans.

Welty in her later years. She lived to be 92, and was treasured in her hometown of Jackson. The main public library is named for her.

Books are everywhere. They’ve covered the coffee table, colonized the dining room table, laid claim to the Steinway piano that Welty’s mother bought in the 1920s by selling quart bottles of milk from the cow she kept in her backyard. Next to the kitchen are the breakfast room and “hospitality area” where Welty mixed cocktails every Thursday night for her best pals. A bottle of Maker’s Mark, the author’s favorite whiskey, stands on the counter.

Welty never married, although she maintained an avid correspondence and romance of sorts — probably unconsummated – with detective writer Ross Macdonald. “As you have seen, I am a writer who came of a sheltered life,” she told a Harvard University audience in 1983. “A sheltered life can be a daring life as well. For all serious daring starts from within.”

By focusing here on three writers, I’ve neglected several others I love: Flannery O’Connor, Edith Wharton, Harper Lee, Joan Didion and Alice Munro. Brilliant stylists, each of whom I look forward to re-reading.

I like male writers, too. Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment and Melville’s Moby-Dick are huge favorites, and although John Steinbeck is spotty his Grapes of Wrath is a thing of remarkable beauty. But overall, it’s the psychological depth of so many women authors — their fascination with our inner lives — that I find illuminating and essential. I am grateful for them.

Thank you for this interesting look at three unsung heroines. I saw a play version of “Member of the Wedding” at my arts camp when I was a young girl. It made quite an impression on me (I remember the Julie Harris version too, of course). But you have given us a closer look at familiar names, whose lives we may not be familiar with. Thank you for this.

Edward, this is lovely! I have long been a fan of all three of these authors (as well as the other women you mention), but I learned something new about each of them in your story. Now I need to go back and re-read them, because it has been too many years.

What a beautifully written tribute to three female authors. I enjoyed reading your essay on women writers as outsiders and observers. I loved the line, “Willa Cather, is remarkable for her great empathy – for the tender, overseeing regard she has for her characters.” The pictures were great. You inspired me to do some reading.

What a great article and very insightful. Willa Cather is one of my top 5 authors.

!!!!!

Edward, this is such a great piece of writing. I am inspired now to read everything these three authors wrote. In fact, years ago you gave me a copy of _A Curtain of Green_ which I still have.

You should find a way to become a teacher of literature. Your insights and clear expression would be invaluable and inspiring to your students.

Thanks!