I can no longer remember if it was I who found the full-sized wooden door lying in the street. If it was anyone else, then the most likely culprit would be Mary Ellen, as she was the only other member of the RAT Troupe who lived in Adams House—not counting Claudio, who participated only intermittently. Mary Ellen and her roommates had taken up residence in a suite right across the hall from me on the first floor of D-entry when Harvard initiated the “coeducational experiment” earlier that semester, spring 1970. She or I would have had reason to be sauntering along Bow Street, where the door was lying. It was an undistinguished door, worn-looking, painted a fading white, and cracked in several places, lying in the street parallel to the curb. It seemed obvious that one coat of dark green paint would be more than adequate to re-christen it for theatrical purposes as one of the doors to our school’s administration building, University Hall.

We painted the door green, and then in white we painted, “Dean of Repression.” We brought the door to the plaza in front of Holyoke Center, and attracted a crowd with our kazoos, our tambourines, and our RAT songs.

Whether it was Mary Ellen or I who discovered the door on the street, we must have summoned other members of our group to help carry it inside to one of our rooms. Most likely, we called on Doc and Steve; they lived together, and were easy-going and flexible, and fit and strong enough to be of assistance in carrying a wooden door to a dorm room. I can no longer picture whose room we carried it to, but I don’t recall transporting it very far, so most likely we deposited it in the living room of my own triple.

My triple had only two occupants, because my roommate Dick had headed to the Radcliffe Quad to take part in the other half of the coed experiment. Doan, my remaining roommate, made very little use of the living room, and was always supportive of my activism. He would have had no objection to anything I was doing as part of my membership in SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) or its “guerilla theatre” arm. He concentrated his own political activism on other Vietnamese students, not just in the Cambridge/Boston area but throughout the Northeast. Doan was part of a network of Vietnamese activists who had figured out how to quickly identify newly arrived Vietnamese students as soon as they showed up on the rosters of American higher education institutions. They would make contact and try to win over these students, to get them to oppose both U.S. policy and the policies of the government of South Viet Nam. He would head off frequently to Northampton, or Saratoga Springs, or Long Island, or the District of Columbia. I got the impression that many of the students he met up with were the daughters and sons of persons highly placed in diplomatic, political, and military circles. It seemed he and his fellow activists, including a Harvard graduate student named Ngo Vinh Long, were having great success in recruiting these students to their cause. He usually returned from his forays very pleased with the results. A notable exception was the time I recall him bitterly and emotionally observing that “Some people, Dale, do not have any loyalty to their country or to their people. They belong to a different country of their own; it’s called the aristocracy! You can’t expect anything from them.”

I don’t have a photo of Doan, my roommate from 1970, but his friend and fellow activist, Ngo Vinh Long, has continued for decades in his activism, advocacy, and scholarship.

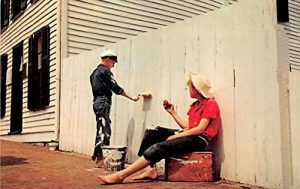

Finding a door on the street was remarkably serendipitous. Members of the troupe had been joking about getting people to pay us for the chance to kick in a door. It would be the RAT Troupe version of Tom Sawyer getting folks to pay him to whitewash a fence, as told in Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. We would use the proceeds to pay off the fine that two of us (Doc and I) had accrued for the damage we inflicted on one of the actual University Hall doors. Now, abracadabra, we had our door! All we needed to do was paint it green (like the original), let it dry, and bring it to the plaza in front of Holyoke Center where we would offer passersby a chance to “kick in” our door for one dollar a pop!

Let me back up. I had entered Harvard in the fall of 1967, so now it was approaching the close of my junior year. I had joined the national organization, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), like so many others, during the “Strike for the 7 demands” in the spring of my sophomore year, 1969. At that time, thousands of students united around three demands related to dismantling Harvard’s chapter of the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC), three others related to Harvard’s role as a major landlord in the city of Cambridge and in the section of Boston where the university had its Medical School and teaching hospitals, and one further demand to start an academic department for African and Afro-American Studies. Although the activists’ jaundiced view of the Harvard leadership prevented them from realizing this at the time, the protesters were successful in winning substantial concessions on each one of those seven demands—including complete victory on #3, which was to “give back scholarships taken away from students who participated in the Paine Hall sit-in against ROTC.’” That one addressed an event that took place in October 1968 and had resulted in me and perhaps 25 others losing our scholarships for the following term. Loss of scholarship was an automatic consequence of being put on probation, and probation was the penalty that had been meted out for our silent gathering in the balcony of the hall where the faculty was scheduled to vote on the future of ROTC. Students from wealthy families had experienced only a symbolic slap-on-the-wrist, while those of us who needed financial aid experienced a genuine and costly penalty. It was very satisfying to see the funds added back when the tuition bills for the fall of 1969 were mailed out.

Most of those who supported the aims of the strike and the antiwar movement were not members of SDS, but during the period from 1967 to 1969, the organization set the tone and provided the leadership for a huge number of sympathizers. SDS split into two main factions in the summer of 1969 (and one of those factions split again) and this fissure, together with the increasing ideological rigidity of all of the factions had a debilitating effect on the organization and the wider movement. Beyond SDS, the anti-war movement was even more hopelessly splintered. One could find printed materials disseminated by the Socialist Workers, the Labor Committee, the Spartacists, the Black Panthers, Progressive Labor, the Bay Area Revolutionary Union, Draft Resistance, the Peace and Freedom Party, the Quakers, Women Strike for Peace, and if you looked really hard, you might even find a newspaper or an adherent of the Communist Party. The most active stuck mostly with their well-known bedfellows, while the huge core of students who had turned the perennial band of radicals into a “mass movement” at Harvard and elsewhere grew tired of it all. Most of the leaflets that my faction of SDS passed out in the spring of 1970 were getting tossed on the ground without being read.

The bright exception, at least on our campus, was the Radical Arts Troupe (RAT). Students who would no longer read a leaflet—indeed, students who had never even attended meetings or rallies–would gather to see our troupe perform skits that lasted five to ten minutes and featured characters such as Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger, and the President of Harvard. We were having fun and we were funny. We were musical. We had kazoos and tambourines. And we had songs—lyrics set to the tunes of the Beatles, the Beach Boys, Smoky Robinson, Christmas holiday tunes, and Roger Miller. The song parodies were my own innovation; when I joined the troupe in the spring of 1969, there were no songs. When most of the old guard left campus, left SDS, or left the troupe after the eventful summer of 1969, I helped rebuild it, and songs became central to our sketches and were the driver of our popular appeal. We had about seven to nine members at any one performance, out of about a dozen who identified as members of the troupe. Although Harvard men still outnumbered Radcliffe women by 4 to 1, our troupe was about one-third to one-half women (Mary Ellen B., Molly B., Ginny V., Ellen M., Liss J., Judith K., and Khati H. are the ones I remember).

We made our first lyrical splash with my version of Stephen Sondheim’s “Call Me Irresponsible,” after the administration set up a Committee on Rights and Responsibilities, in order to create an orderly process for kicking out students who were involved in disruptive protests. (The process they had used to suspend and expel students after the “Strike for the 7 demands” had been cumbersome, requiring too much time at faculty meetings.) Invading one dining hall after another, uninvited, we swaggered in as if we were members of the Harvard administration—but brandishing cap guns–singing, “We’re right, you’re responsible. Yes, you’re reprehensible. What’s more–you’re dispensable too.” Students weren’t that thrilled initially to have their dinner interrupted, but once they saw we had game, the vast majority listened politely and many cheered enthusiastically when we were finished. (The brevity of our theatre pieces was much appreciated, no doubt.) After that, there was a song about bringing the troops home, to the tune of the Beach Boys’ “I Get Around.” “Home, home, bring ‘em home, bring ‘em all home.” And to the tune of “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” was this lyric: “Southeast Asia/Has got that somethin’ (vocalized guitar bridge)/Big business understands/Cheap labor/and resources/(vocalized bridge)/On which to put our hands.”

At least half of our RAT troupe did not identify as members of SDS, although the RAT was affiliated with the Worker-Student Alliance faction of SDS. Our values and priorities, as translated into our theatrical sketches, reflected the broader vision that had existed before the split in SDS. We went out of our way to avoid the ideological nitpicking that generated constant friction among the factions. In fact, one hard-line graduate student took the microphone to denounce us after we performed at an SDS fundraising party, specifically because of the lyric, “Bring ‘em all home.” To him it it approximated the slogan used by the Socialist Workers Party, “Bring all the troops home now,” and that was unforgivable, because the SWP was a Trotskyist brand, while he, and the Worker-Student-Alliance more generally, drew their ideology from the Progressive Labor Party–claiming the mantle of Marx, Lenin and Stalin. We RAT troupers looked at each other and smiled, and passed around our jug of California red wine. We were oblivious to their critique because we weren’t trying to get into their club.

One of our trademarks as a troupe and one of mine as a lyricist was incorporating funny references that weren’t specifically political, as in the person playing Nixon in our sketch claiming we had certainly not gotten ourselves involved in every country in Southeast Asia, because, “Henry, we’re not in Siam yet.” Our Kissinger character had to tell him, in a most patronizing tone, that “Dick, Thailand is Siam.” In the same vein was a lyric referring to a much-publicized White House wedding: “And get your bombs, (yeah, yeah, yeah get your bombs) clear out of ‘Nam; not to Laos or Guam, or even Tricia’s prom.”

The invasion of Cambodia by Nixon and Kissinger in the spring of 1970 once again infuriated the vast majority of students and reawakened the spirit of mass protest that had lain dormant for a number of months. A national student strike shut down roughly 100 campuses. Besides the unifying national demand to withdraw all troops from Southeast Asia, our demands at Harvard included the elimination of war-related research, the firing of faculty (including Henry Kissinger) whose Harvard appointments were being held open for them while they were on leave to engineer the war, and an end to the repression of students and workers who had been involved in protest activities. I put these demands together in a song based on “The Book of Love,” released in 1958 by the Monotones.

In the summer of 2023, I began recording the songs of the RAT Troupe and turning them into videos. Here is WHO WROTE THE BOOK OF WAR, with only one minor update in the lyrics from the way we sang it in 1970..

The RAT practiced the new song, and then proudly performed its world premiere in front of a large crowd gathered at University Hall on the first full day of the national student strike. Doc and I were on the top step and other members of the troupe were on the next couple of steps going down. Listen to the original by the Monotones and you’ll understand that the song requires an explosively strong beat in one specific place within each chorus. There is a vocal pause right after, “we wonder, wonder who, whommbadoo-ooh,” and before the query, “Who wrote the Book of Love?” That pause is filled by a loud percussive beat. In the interest of artistic integrity, Doc and I were doing our best to replicate that beat by banging one foot apiece against the door of University Hall each time the chorus came around.

Apparently, unbeknownst to us, our artistry caused cracks in the door. And that is why we both received letters a week or so later, accusing us of “willful destruction of university property” and summoning us to separate hearings on the top floor of Holyoke Center, where the Committee on Rights and Responsibilities (CRR) would hear our case and determine our fate.

We fired off a letter that was printed in the daily student newspaper, the Harvard Crimson. We noted that just weeks earlier, the rather raucous cast of the play Marat/Sade, performing in the Adams House Dining Hall, had inadvertently shattered a window. Those responsible had not been called to a disciplinary hearing but merely asked to pay for the window. Clearly, we stated, this was just another example of political repression; there was the same kind of inadvertent damage in both cases but ours was being treated differently because of the political context in which it took place.

Someone in the administration either read our letter or concluded on their own that their punishment would look like blatant political retribution. Doc and I received follow-up correspondence that released us from the “willful destruction” charges and instead required us to pay for the damage—somewhere in the range of $120.00.

And that is where things stood when we found ourselves joking about getting people to pay for a chance to kick in a door, wondering where we could get a door, and then finding a door on the street! Someone bought some green paint and some white paint and a couple of brushes. We painted the door green, and then in white we painted, “Dean of Repression.” We brought the door to the plaza in front of Holyoke Center, and attracted a crowd with our kazoos, our tambourines, and our RAT songs.

“We got in trouble for kicking in one of Harvard’s doors!” we would announce loudly to passersby. “What have you done for humanity lately?” It was amazing how many people took us up on the offer. Someone asked if he could have three kicks for $2 instead of just the one for a dollar. Sure! Others threw in a fiver. Others tossed in coins or bills without even taking a crack at the door. None of the people who paid to kick the door looked like college students. They were anywhere from high school students to people in their sixties. We were having fun, and so were they. The door seemed impermeable to the first few kicks, but by the end, it was destroyed. We collected well above the amount we needed. Doc and I paid off our debt and we donated the remainder to SDS.

A week later, I got another letter from the CRR. I was going to be kicked out after all—but not for my artistic expression. Just for “interfering with the essential functions of the university.” (That is, being one of hundreds of students on an obstructive picket line around University Hall) Some of us, however, still wonder—who wrote the Book of War?

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Whew, Dale, fantastic story, and you absolutely got into good trouble with consequences. I’ll never think of that Monotones song in the same way again. I was still in high school during that time so didn’t participate in the most intense demonstrations, although later at Mills we experienced the heavy presence of the Black Panthers.

I’m not sure if you may have actually read this story while I was still doing the final edits, including figuring out how to put up the video of the Monotones! But thanks for all the comments, and now, if you go back, you can sing my lyrics while listening to the original.

You have written before about being expelled from Harvard, but now we have the exact story of why. Like Marian, I was still in high school at this point in time, so removed from student activism (Brandeis was the epicenter). You describe it with great bravado. We understand your motivation and execution. I think university administrators have come a long way in the intervening half century, but were definitely not enlightened at the time. Thanks for filling us in on all the details.

Dale, thanx for more insight into your radical college days!

I was out of school by ‘64 and not involved in the politics of the time. In fact my college squeeze was in ROTC and I must admit I loved him in his uniform. (I’m glad to say he went on to be a staunchly liberal lawyer.)

A few years later I was on the Columbia campus for grad school when things started to heat up. I was still no where near an activist then, but very glad now to experience vicariously the good SDS trouble you got yourself into!

Bravo RAT!

Dale’s brilliant and hilarious song’s were a highlight of my senior year. Performing in the Radical Arts Troupe was a lot more fun than writing, mimeographing, and passing out leaflets, and got our points across better, I’m sure.

I don’t know how I missed out on the Radical Arts Troupe, I would have certainly joined if I had known. Singing and radical politics were my two extracurriculars in college, and it seems like you combined them nicely. Maybe it was because you were performing down at Harvard, and I was still living up at Radcliffe at the time. Anyway, thanks for this fun story about some good trouble, and now let’s all sing “Who Wrote the Book of War?” together!

Good story about the door, Dale, and sorry I missed the performance in front of Holyoke. Though I might argue that, even though it didn’t prevent you from being kicked out, raising money to pay for the door on University Hall — and it sounds as if you did, in fact, turn over the amount owed to the Powers That Be at Harvard — is not really trouble, but restitution. Maybe you should have put it in the Nathan M. Pusey Escrow Account, to be released only upon Pusey’s resignation as Harvard’s president. I guess it’s a little late for that now, though.

Also liked your rendition of “the Book of Love.” In fact, I remember having a deep discussion with a musical friend of mine when the song was released about why you would ever name your singing group the “Monotones.” Isn’t the whole idea of singing – -as opposed to, say, Gregorian chants — to use more than one tone? Please feel free to discuss further.

John, every good lawyer deserves a clear response even if their appraisal of the work is, well, lawyer-ish. (I say this as one who is proud of a father who practiced law and a sister who still does). Yes: paying Harvard back for the door was straightforward restitution (same as the actors in Adams House); it was all the other related activities (being involved in SDS, being in the RAT, disturbing people’s dinner discussions in the dining halls, stopping deans from getting into their offices, and asking citizens passing by to kick in a replica of a University Hall door)that was the “good trouble,.”

My research fails to determine why this group of young men (about 18 to 21 when they put the song together) used such a self-mocking name for their group, except for the inference that they were deliberately being, um, self-mocking; see above about questions posed by lawyers!) But I did find out in more than one place on the web that what inspired the song was the commercial for Pepsodent toothpaste. “You’ll wonder where the yellow went, when you brush your teeth with Pepsodent.” It went from “you’ll wonder” to “I wonder….” Which makes me feel good about the fact that I helped it evolve lyrically just a little bit further.

Good points, Dale. And, by the way, I really enjoyed seeing your featured image from the Harvard Stadium meeting.

As to the monotones, my bet is that the group assumed that its name meant that they were all singing the same notes at the same time. I guess that’s better than calling yourseves the “Out of Tunes.”

What an amazing story, Dale. Those were repressive times, indeed. I love the lyrics you wrote to popular songs as protests. I was actually singing “Who Wrote the Book of War.” Your actions in protest of an unjust war were the essence of good trouble, and RAT certainly made some noise. BTW, I ordered your book and am eager to read it.

So happy that I actually got you singing my lyrics to the wonderful Monotones’ tune and beat! And please share any comments on the book at dale.fink@gmail.com. Thanks for your interest!

Talk about ‘good trouble,’ Dale! And you hit Harvard at a very rowdy time. I had just left, a year late (class of ’66) and despite the temptation to throw my fourth year over, I finished up in ’67. I appreciated you listing and discussion all the activity around the four demands, and, when I say “you deserved it” re: your expulsion, you know I congratulate you from the common grounds of rebellion we both have trod.

And what a clear distinction you forced: Marat Sade vs “The Book of War.” Really. Congratulations on your art and ingenuity. You clearly stirred up some darned good trouble!