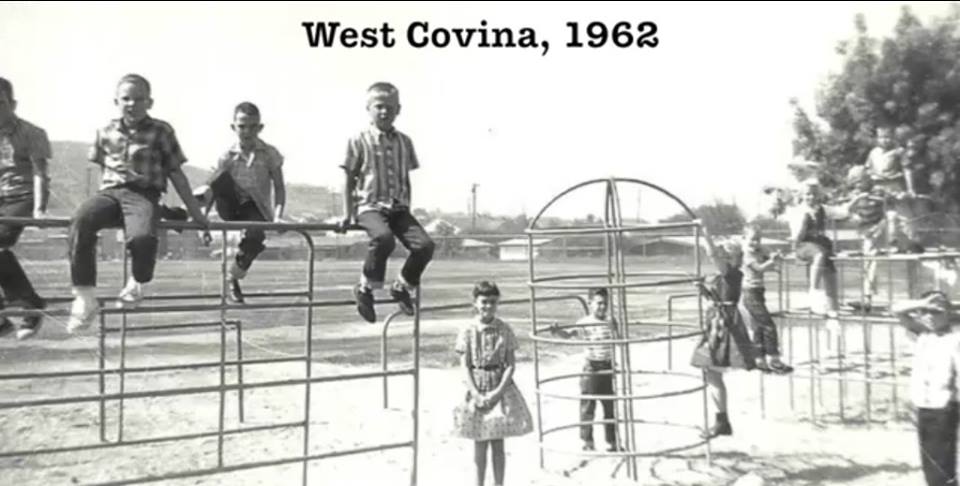

This photo reminds me of the classic shot of crows gathering menacingly on the jungle gym in Hitchock’s “The Birds.”

The last time I saw Diane Westin she was six years old. I remember a sweet smile, lustrous brown hair and the last vestiges of baby fat. She probably wore a flower-print dress, shiny black Mary Janes and white socks.

Social hierarchies are quick to develop in junior high, and from day one Diane is Queen Bee. Girls copy her, lobby to be her friend. Boys stare and whisper and grunt. Without question she is the most desired, the most alluring girl in seventh grade.

That was kindergarten. Diane and I were best friends that year but now, in my first week of seventh grade at Cameron Junior High, she is someone I barely recognize.

At 12 she’s prematurely developed, a suburban Lolita with the haughty self-possession of a young woman. When I pass Diane in the hallway, or when our eyes meet in the cafeteria, she doesn’t smile or say Hello – even though I’m certain she remembers me.

Sue Lyon in the movie “Lolita,” released in 1962 — the year Diane Westin was Queen Bee at Cameron Junior High. .

I don’t say Hello, either. Six years is an eon in a child’s life and during the long gap when we go to different schools– new friends, new experiences, all of that unshared with each other — we’ve become complete strangers. Throughout seventh grade and all of high school, in fact, we never speak to each other.

And yet I’m fascinated by Diane and her apparent fearlessness. Can a 12-year-old girl swagger? Diane does. Gently swishing her hips, she walks down the hallway like pre-teen royalty, looking calmly from side to side to appreciate the effect she’s having. She has full lips and bright eyes and wears V-necked sweaters that emphasize the contours of her breasts. Without question she is the most desired, the most alluring girl in seventh grade – a form of power she clearly enjoys.

Social hierarchies are quick to develop in junior high – it isn’t called middle school until years later — and from day one Diane is Queen Bee. Girls copy her, lobby to be her friend. Boys stare and whisper and grunt. There’s a patriotic song, “I Like It Here,” that we all learn in Miss Booth’s music class that year, and during recess Diane leads a rowdy tribe of girls across the playground, loudly singing the anthem and mocking its cornball lyrics: “Lift my head to the sky, and say how grateful am I! Yes, I like it he-e-re!”

A rumor develops that Diane and a seventh grade boy are already having sex. In 1962 the notion itself is scandalous. Maybe it’s untrue, a fiction generated by jealous girls who covet the attention Diane easily draws to herself. True or not, the story is so titillating, and Diane such a compelling, provocative figure on campus, that most of us enjoy believing it.

Compared to Diane, I’m a misfit. Awkward, unsure. My teeth are crooked, I’m uncoordinated and bad at sports, and the bullying that seventh grade boys exhibit with escalating frequency intimidates me. It doesn’t help that my homeroom teacher Mrs. Kiser is conspicuously prone to picking class favorites, even flirting with the handsome, physically mature boys. I feel second-class.

One afternoon I go to Von’s supermarket with my mother. I kill time in the magazine section while she shops and later I find her at the front of the store, talking to a vaguely familiar, gray-haired woman. “Eddie, do you know who this is?” my mother asks. I don’t. “This is Mrs. Westin, Diane’s mother.”

There’s a careworn, defeated look on Mrs. Westin’s face. She doesn’t say much in that short conversation, but I get the impression from her sad eyes that she’s consumed with worry over her out-of-control daughter. She’s much older than most moms – over 50, I would guess — and the job of raising a willful, sexually mature pre-teen is more daunting, I’m sure, than it would be for a younger woman. Looking back, I hope she had someone to talk to, and didn’t hold all that anguish inside.

Junior high is a horror show for everyone – kids and parents alike — and I’m a reluctant but captive participant. Kids are meaner, cliques more rigid, the pressure to conform unrelenting and perplexing.

Lloyd Thaxton, with James Brown. I learned to dance by watching Lloyd’s show every day after school.

What saves me are two or three friends who carry over from sixth grade, plus my love for movies and music and reading. I devour To Kill a Mockingbird, my first “grown-up book,” and the movie version with Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch comes out the same year. His performance and Harper Lee’s themes of tolerance, decency and parental love have a profound affect on me. I buy my first 45 rpm record in seventh grade, The Four Seasons’ “Walk Like A Man,” and learn to dance by watching The Lloyd Thaxton Show five days a week.

Seventh grade is tough but eighth grade, when hormones ignite at greater levels and my teachers are masters of humiliation, is much worse. I’d love to swipe the memory of those ogres from my brain: Mr. Michaels, the snakelike, bullying industrial arts instructor; Mr. Weaver, a bitter asshole who shoves a large wet sponge in my face when I yawn in math class; Miss McDermott, a steely-eyed despot who could have inspired Nurse Ratched in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest; and my homeroom teacher Mrs. Bremer, whose dearth of charm suggests a replicant engineered to perform tasks without emotion.

The Beatles with Ed Sullivan, 1964. A great band, but also a distraction from the chaos of adolescence and national tragedy.

Academically, eighth grade is a disaster for me. It’s also the year JFK is killed. How many 13-year-olds have the wisdom or experience to process a jolt like that? Two months later the Beatles explode on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” They’re a phenomenal pop band, but for teenagers in 1964 they’re also an intermission from the chaos of being young and the recent knowledge that something so basic — our faith in a safe and just America — is irrevocably compromised.

I started my story with Diane Westin, and the experience of writing this piece has made me think about her more than I have in 50 years. I can barely picture her in high school, but an old West Covina friend recalls that Diane hung out with the “hard” girls on campus — the ones who teased their hair, wore tight skirts and lots of “bugger-off” cat eye makeup. “She was very smart and kind of full of herself,” my friend says, and after high school she became a “hardcore born-again Christian” and renounced her wild, unruly teen years.

And then what? I have no idea, but I would love to know. I haven’t used Diane’s real last name here, but if by fluke she happens to see this essay she will recognize herself. I hope you’re well, Diane. I hope you made peace with your mother long ago. I mentioned that you seemed powerful and fearless in seventh grade, but the more I think about it I’m sure your story has layers of complexity. Were there family conflicts, private sorrows and insecurities that you masked with that brazen toss of your head?

We all develop survival strategies in tough times. The brutal, bewildering years of junior high would be insupportable without them.

I love the painful detail in which you recall how an early childhood playmate became a haughty, precocious, pubescent teen who wouldn’t give you the time of day. You paint the whole world richly; I chuckled at your vicious (yet well-deserved) capsule descriptions of your teachers.

My 6th-grade class had a Diane equivalent named Nancy Jo, and I have to confess that we boys felt some schadenfreude of solace when she got pregnant senior year. So I salute the compassion you find for Diane by story’s end. No doubt her experience, which seemed charmed, had its share of pain.

Thank you, John. That was a hard one to recall and to write. Amazing how raw some memories remain.