To commemorate the 50th anniversary of Women’s Suffrage in the United States, record numbers of women march along 5th Avenue, past a banner that reads ”Women of the World Unite!’, New York, New York, August 26, 1970. (Photo by Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images)

For me, women’s liberation began abruptly in 1969. I was working with a theater company that deployed guerrilla theater in San Francisco’s parks. We had developed a show about Noah and the apocalypse, a grim but hilarious metaphor spoofing our wartime paranoia.

exploring chauvinism felt like tumbling through surf

We had plenty to be paranoid about.The world had burst into flames. The ecstatic apogee of the Chicago protests, the spring rebellions in Paris and Prague had been driven underground. Weatherman destroyed SDS and charged into their days of rage like angry children. Black and Chicano power splintered and turned nationalist. The FBI and local cops killed forty-nine Black Panthers that year, Nixon took the White House, and the war raged on.

“Noah” was a righteous show, or so we thought. We used a Brechtian gizmo called a cranky as the centerpiece of our portable drama. Mounted on a stepladder, the cranky consisted of two spools of butcher paper set in a wooden frame. As an actor cranked the spools, colorful illustrations rolled across the paper, adding impressions to our musical tale of the Biblical patriarch and his rainy fiasco.

My mother attended the show one sunny day. We were performing in Golden Gate Park when two women showed up at our performance and trashed us. “Hey!” they shouted, pointing to the cranky and an incidental cartoon of a naked woman in a shopping cart. “What do you think she is… a piece of meat?!”

The intensity of their protest stopped the show short. Actors and musicians, male and female, froze.

“Pigs!” the women shouted. “What does that image say about women? What does it say about you?”

Dumbfounded, I stared at the cranky image, a white-skinned, big-breasted, blonde stuffed into the shopping cart. Her presence served no purpose, did not support the story, was not mentioned in the script. I experienced a momentary whiteout, a shock of recognition. The two protestors were right! They were right on!

I turned to my mother. Behind her dark, intelligent eyes, she seemed to be re-calibrating her entire life.

*

That was the beginning. Feminism roared through San Francisco like a tidal wave. Men didn’t know what hit us. Women didn’t fully understand why they were striking out. But they did. They knew something was wrong.

At first, women had no words for their rebellion. Political correctness rose out of discourse, carrying validation, a useful tool to protect newborn notions and infant vocabularies.

For men who dared to reflect, exploring our chauvinism felt like tumbling through surf, salt water in our lungs, sand up our noses, skin scraped raw as we were thrown ashore, then sucked back into the maelstrom.

Back then, men didn’t become feminists; we supported feminists or reacted against them or struggled with both. Feminism set off a battle within ourselves to understand how deeply our dominant roots had crept into our brains, our DNA, into our expressions, assumptions and our now-exposed behavior.

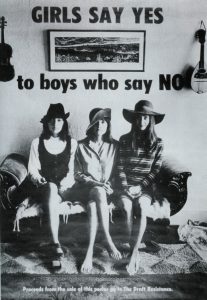

Changes came, slow at first, then accelerating. The formerly radical draft-resistance poster of Joan Baez and her sisters looking cute and saying “Girls say yes to boys who say no” became a symbol of chauvinism on the left. What had been a clever plug for draft resistance flipped into evidence of the depth of sexism.

Changes came, slow at first, then accelerating. The formerly radical draft-resistance poster of Joan Baez and her sisters looking cute and saying “Girls say yes to boys who say no” became a symbol of chauvinism on the left. What had been a clever plug for draft resistance flipped into evidence of the depth of sexism.

Women gave no quarter. Why should they? They’d endured a myriad of male-inflicted traumas for millennia. In political meetings, women demanded to be heard. The men, leaders of the revolution, first ignored or ridiculed them.

When you push hard, power pushes back, even from the most unlikely directions. Abbie Hoffman claimed that a women’s place in the revolution is on her back. Fuck you, Abbie.

Liberals patted feminists on the head, saying “You’ve come a long way, baby.”

Dragging at us from behind, the frightened straight world copped a titillating feel for bra burning. The media invented diminishing terms — women were radicals, militants, man-haters, bra-burners, the PC police. They characterized the new rebellion as strident, perverse, wanton, and a threat to society

Women evoked Lysistrata to protest the ages-old Peloponnesian war between men and women.

Feminism became as immediate as Vietnam only closer. Here at home, we had met the enemy, and they were us.

In those first, raw years, if you were savvy enough to listen and tough enough to stay open, you could allow yourself to learn from women sought to discover their power and define their rebellion.

If you went with the flow, lovers might learn that lovemaking was a dance, not a solo routine.

Men who resisted seemed to harden like concrete, male versions of Lot’s wife. “Don’t look back,” we chanted. “Freedom lies ahead.”

Visual attraction posed a dilemma for both sexes. What did a woman’s body represent? What did women’s brave new lives express? Was there intent in appearance? How did men respond? With new notions of gender neutrality or with rape?

Men struggled to dissolve guilt at our transgressions before it became resentment. We succeeded and failed.

Women struggled to understand the depth of their oppression and take personal and political responsibility for their liberation. They succeeded and failed.

The personal had become political.

The political had become personal.

Awareness blossomed. Confused, committed, conflicted and ecstatic, we learned how to march together through the meadows, singing glorious songs of freedom.

Now feminists know more than we did about their place in the world and the obstacles they face. They know how to huddle and strategize. A third wave of feminism has progressed from raising awareness to raising hell.

Nothing can stop them now.

Nothing can stop us now.

# # #

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

Wow Charlie, you capture that era and the whole experience so well in your powerful prose! This is a story I will enjoy reading multiple times, because there is so much there.

I had that poster of the 3 Baez sisters in my college dorm room. I loved it. It never occurred to me that the message was sexist. I guess it suggests doing the right thing – resisting the draft – for the wrong reason? But really, if you do the right thing, does the reason matter? Apparently Joan thought it was okay, or she wouldn’t have posed for the picture.

Thanks, Suzy. I’m glad I offered up food for thought! Re the Baez poster. I tried to use the Girls say ‘yes’ notion to illustrate how quickly things changed. I think the poster was done by activist David Harris, Baez’ boyfriend. At the time it was made, the poster was charmingly acceptable. One year later, the notion of girls offering their bodies for political reasons seemed like retro politics to many feminist thinkers. Not pro or con about those times, but the sudden shifts represent to me, the turmoil of the times. There were many casualties, but the movement lives on.

“She seemed to be recalibrating her entire life” Whew…a lot to unpack! The whole history of the first wave. I was a little too young to be really caught up in the moment, so I’ve learned so much here. As Suzy says, I’ll reread this many times. When I interviewed at Northwestern in 1969, during the beginning of the tumult, I wanted to learn about their theater department. They (honestly) asked me if I would burn my bra! Furtherest thing from my mind at the time. During these crazy times, it is good to remember how far we’ve come and pray we don’t ever go back. Thanks for the stunning reminder, Charlie.

Thanks, Betsy. I feel like a bit of an interloper, although the people, events, and ideas did feel like a maelstrom. I think your bra-burning experience was just part of the condescending sexism that men got off on, as women began to refuse their dominance. And no, we won’t ever go back. As Orwell says in 1984, (paraphrasing) there are some things they can’t take away from you.

Your story captures the awkward dance of trying to see outside our upbringing to a new possibility, like a fish trying to imagine what the world would be like without water. As you observe, both women and men struggled with this, though even well-intentioned men were at an ironic disadvantage since it is so hard to see outside our own privilege. If we were lucky, we had good, forgiving women to instruct us. But I think all of us have felt ossified into pillars of salt way too often.

Great simile, John, the fish with an imagination. It did feel like that, didn’t it, impossible to grasp, like another universe. And yes, I think those of us who found women who were willing — and able — to carry on discourse about sexism may have amounted to a lucky few who didn’t reject feminism out of reaction. And yeah, pillars of salt also gets it. As someone in my Harvard 25th reunion said, some of us fell backward into the 50s while others fell forward into the 60s.

That’s a great line about ’50s vs ’60s. It’s true of my class too, even though I was a few years behind you.

This is breathtaking Charles! You remind me of the famous Sandra Bartky quote: “Feminists are not aware of different things than other people; they are aware of the same things differently.” The issue with consciousness-raising is that if yours is the only one raised, it makes it nearly impossible to function in the real world. Many of us found ourselves in a lose-lose situation, we had to reject the past, but the future we needed didn’t exist yet. It still doesn’t.

Beautifully put, Patti! Having been aware differently most of my life, due as much to circumstance as sensitivity, I often feel incapable about my world view, my assessment of the ever-changing (but never enough) landscape, from the personal to the political. And yes, ‘the future we needed didn’t exist yet.’ I’ll never fully recover from watching our hard-won gains dissipate in the late ’70s and ’80s and the diverse defenses we all put up, like boards tacked across an embattled doorway. My wife Susan, a fellow traveler from all the way back, wrote a beautiful play (now on the boards) about hope and despair by doing a gender twist on the Faust myth, the result of her long struggle to keep hope alive. http://lat.ms/2np8DrJ

As Bartky said, ‘[we] are aware that we see the same things differently.’ And how do we manage to retain some semblance of sanity? Thanks for your remarks.

Thought you would be interested in this comment on the Baez poster from Jim Stodder, posted today on the HR71 listserv:

Let me say a few words in defense of the “Girls Say Yes” poster of the Baez sisters. I was one who thrilled to the music of Joan, and that of Mimi and her husband, Richard Fariña. (Richard died the year before we entered HR; Mimi and Pauline are now gone as well.)

I thought and still think of this as a tasteful and appropriate use of women’s sex power. Why not? That power has been used far more often to send the lads marching off to war. Take it from Aristophanes. The ladies here are seated demurely and hipply in their wide-brim hats.

I will further confess, to no general astonishment, that it was images like this, and more generally the women of the New Left, that ‘recruited’ me to their various causes. A decision I have never regretted. They were and are the most interesting and attractive women around — why look anywhere else?

This is a right-on quik discussion about the poster. Very smart and sweet. And indeed, ‘why look anywhere else?’ for smart and attractive women. I was using the ‘Girls say yes…’and feminism’s response (not a unified position by any means) as an example of how high the stakes were in that newborn press by women to be taken seriously in their resistance to the sexism that continued in the New Left. In spirit and thought, I can understand HR’s position today. But back then, the appropriate use of women’s sex power was up to each woman. Some women chose to call out New Left leader David Harris’ poster and it’s interpretation of women’s power. Who got the final say on approving the poster? Just a brief sign of the times.

Thanks for linking me back to this post. Your descriptions sure brought back those times for me, and indeed it was a time when we were looking at everything with new eyes. Hard to imagine having that cranky like that today. Much has changed, but sadly that feminist perspective struggles to be recognized still.

Thanks for reading, Khati. I got carried away! Beyond the retro call! I’m trying to recapture the contradictions between male power and women’s resistance in those ‘righteous’ times, while we were all trying to reach a common goal. AAnd then came Mao’s little red book and our own peculiar version of the cultural revolution. Yikes!

This is so clear and so accurate and so hopeful. Thank you for understanding without needing constant explanations that sexism is no better than racism or any other diminishing treatment of a specific group. Beautiful job!

Thanks, Susan. I wholeheartedly agree. The link between racism and sexism was part of the awareness that we have all shared and acted upon from the beginning of our movements and was being brought forward as far back as Seneca Falls in 1848… and before.