His name was Bob Scollard. He was a bit over 40 and grew up in South Boston: a white guy with close-cropped sandy-colored hair, average height and build and a receding hairline.

He must have noticed that the word “kidnapping” shocked us. He took the time to give us the word-for-word definition from the California Criminal Code: “Moving another person a substantial distance, without the person's consent, by means of force or fear.”

My friend Claudio and I met him in Harvard’s Adams House dining hall in late September of 1971. We were members of an activist organization called Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and the two of us had volunteered to get to know him and find out if he would be open to SDS involvement with his situation. If he wanted our support, then the membership would discuss it and determine whether to launch a campaign to help him fight to get his job back.

What we knew about Bob was that he had been a full-time chef at the Harvard Club of Boston, after previously working as a cook in one of the Harvard residence houses. The Attica prison uprising had come to a bloody end on September 13th of that year when New York’s Governor Nelson Rockefeller sent in the state troopers, killing 33 inmates plus ten correctional officers. A few days later, Bob had shown up—unknown to the event’s organizers–and stepped forward to speak briefly at a rally whose purpose was to denounce Rockefeller and express solidarity with the surviving and slain prisoners. Bob had identified himself during his remarks as someone who had served time in prison and had great sympathy, knowing the conditions these men had faced.

The Harvard Club had fired Bob a few days after he spoke at the rally, which had taken place outside his working hours and far from the Club premises. The Club did not want to appear to be interfering with his right of free expression. But they were anything but forthright about the rationale for his being terminated. I found an article from the daily student newspaper, the Harvard Crimson, that quotes the manager of the Harvard Club attributing the firing to “untidiness.” But Bob had not been written up for that or received any negative performance reviews in his year on the job.

We all believed—along with Bob—that they fired him because the Club did not want a former inmate gracing their kitchens—did not want the alumni who dined there wondering which of the men walking around under a white chef’s hat was in fact a formerly incarcerated felon. Worse than that: a formerly incarcerated felon who was vocal and assertive enough to speak at a rally organized by “student radicals.”

My impression from the way Bob described his work as a chef—at the Club as well as on campus—was that he took his professional duties seriously. He told Claudio and me about a cook who had only been working a few days in the Quincy House kitchen. The guy arrived late one morning, and his assignment was to make the scrambled eggs. The standard procedure was to crack about six to eight dozen eggs into a huge stainless-steel bowl, which sat under a motorized mixer. Turn on the mixer and as the bowl spun around on its stand, all those yolks and whites got scrambled into a massive glob of yellow in just a few minutes. Then add salt and pepper and dump it all onto a baking pan. Check their progress, move the eggs around intermittently with a spatula, and soon you would soon have a nice batch of “baked” scrambled eggs.

Bob was busily engaged on some other element of the breakfast. He watched in mild amusement but mostly in horror as the new young cook rushed to grab some cases of eggs out of the refrigerator, bring them over to the mixing bowl, and then dump them rapidly into the stainless-steel bowl—without cracking them! Bob was already imagining the supervisor giving the poor bastard his walking papers later that morning.

As Bob continued to observe, the cook switched on the mixer and the machine began to beat up the eggs–shells and all. As the mixing bowl rotated, Bob noticed the new guy didn’t panic; he went to a nearby drawer and grabbed a large, slotted spoon. With the spoon, he began pulling out broken shells that floated to the surface of the bowl. The young guy turned the mixer to an even higher speed, and the mass of eggs were whirring around faster than was usually recommended. The new cook remained cool as a cucumber. Sure enough, the force from the rotation of the bowl sent more and more shells to the surface. In a matter of minutes, the guy seemed to have collected all of the shells. The guy was dumping the whole mess of well-beaten eggs into a baking pan. He wasn’t such an idiot after all; he had saved himself 10 minutes by not bothering to crack the eggs, and now he was back on schedule. Bob could appreciate the cunning and ingenuity of the new guy.

I would have several opportunities over the next few months to see and sample the results of Bob’s own cooking. He did respond favorably to our offer to go to bat for him, and SDS did mount a campaign to fight for his job, mostly by picketing the Harvard Club of Boston. We were hoping to generate negative publicity for the Club that would embarrass them into changing their minds. They never did change their minds and eventually Bob would have to seek other employment. For a few months, however, SDS was able to help sustain Bob financially by organizing several fund-raisers on his behalf. Bob would plan a menu and prepare a meal, and students would pay $15 or $20—big spending at that time, especially for those who had meal plans and didn’t ordinarily have any expenses beyond that for meals. He prepared steak and beef dishes such as Beef Wellington. Sides I remember included whipped potatoes with butter, rice pilaf, and green beans almondine. Once he confirmed there was a student who had access to storage space in a freezer where he could keep the trays until it was time to serve dessert, he made Baked Alaska on more than one occasion. I had never heard of it (it’s a fancy version of an ice cream cake), but I found it to be scrumptious and well beyond any dessert I had been served in the dining halls. I was never involved in collecting the money from these dinners, but we had enough takers that I’m imagining Bob cleared $800 to $1000 or more for each of those dinners after the expense of purchasing the ingredients.

When Claudio and I first met up with Bob, we weren’t having a meal together. I was affiliated with Adams House but living off campus my senior year, after being away the previous year; Claudio rented an apartment somewhere else off-campus. In between meals, anyone could come into the dining hall and get some hot water and a teabag or some self-service coffee. Since Bob had formerly worked in a different House kitchen and knew his way around the campus, we figured it was a convenient and comfortable place for us to meet each other and have a conversation.

We found Bob waiting for us. We grabbed some tea or coffee and exchanged pleasantries. I’m sure I read the witticism on my Salada teabag label before proceeding with the conversation.

Claudio and I hadn’t made a specific plan for what to ask Bob. Since he showed up at the Attica solidarity event, we imagined him as someone who had a history of fighting for social justice. Maybe he had gotten into a scuffle on a picket line or tussled with a tyrannical boss on an assembly line. Somehow, he’d been arrested and convicted and ended up serving time. Claudio himself had served 30 days in a Massachusetts prison a year earlier, resulting from his attempt to attend a meeting at the Cambridge City Council, during one of their perennial debates about rent control. The cops (as instructed, no doubt, by their Chief and the City Manager) were deliberately letting in the representatives of the property owners and keeping out the tenant activists. Claudio was among a half-dozen of the latter, arrested for disorderly conduct as they tried to push past the gendarmes.

Here was this man seated with us who had stood up for the Attica Brothers. What movements had he been affiliated with? What would be his story?

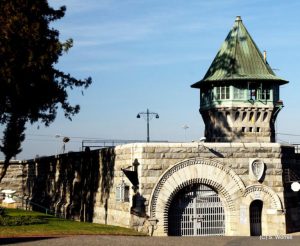

I don’t remember exactly how we got the conversation started, but Bob knew why we were there. Without fanfare or preliminaries, he laid it out for us. He wasn’t at all circumspect. He had served ten and one-half years in the California penal system. I’ve always remembered that number because it was so specific. His time was divided between the prisons at San Quentin, Soledad, and Folsom.

A judge had handed down to Bob something I had never heard of before: an “indeterminate life sentence.” That was an artifact of the California penal system; I have still never heard of another state adopting it.

It was one of those “liberal reforms,” I would learn later, that are designed with some kind of humanitarian impulse but actually make things worse, analogous to other terrible ideas that sounded good if you didn’t look into them very closely, like “urban renewal” or “ending welfare as we know it.” You could get “one year to life,” “five years to life,” “ten years to life,” or any number “to life.” In the thinking of its advocates, the “indeterminate” aspect of the sentence allowed the judge to set the minimum lower than it might be otherwise, and then the system could reward you if you were compliant and productive. You might get “five to life” for an armed robbery instead of, say, a flat ten years. Then (in the minds of the “reformers”) you had the motivation to be a model prisoner and get out after the minimum time was served.

What the “reformers” didn’t really consider (or care about) was that the “indeterminate” sentence meant the Parole Board held your life (well, your freedom) forever in its palms. You lived with the hope that you’d get out once you served the minimum, but you were haunted every day by the possibility that they would never let you out. There was no certainty it would ever be less than a life sentence. The Parole Board claimed to make the determination based on your conduct behind bars, your showing of genuine remorse, and other factors. But every move you made, each action you took as an inmate was subject to their interpretation. When they denied you parole, it was also up to them if you came back for reconsideration in one year, two years, or an even longer hiatus.

Bob Scollard—or Bobby as he was known to his family and peers—had to endure the torment of going up before the Parole Board each year, starting after year five, until the members of the Board decided he was sufficiently “reformed” to let him live as a free citizen after those ten and one-half years.

And what militant action on behalf of the working class had led to that sentence? Again, Bob didn’t wait for us to ask. He told us he had been convicted of armed robbery, kidnapping, and attempted murder.

Claudio and I sat at tables in the Adams House dining hall hundreds of times in the years we each lived there. We had heard political arguments, sexual braggadocio, and theater types practicing their soliloquies. But when we heard these words from our new friend’s mouth, I think we both wondered if we were the right guys to finish this conversation. Claudio and I exchanged furtive glances. We weren’t quite prepared for how to respond to this new information, It was a long way from rushing past a line of police at the local City Council.

Bob probably sensed our unease and our uncertainty about how to respond. Helpfully, he began to add some context, to help us grasp the shape or contours of his life trajectory. He had grown up in “Southie” (South Boston), and most of the young men in his crowd either went with the Boston Police Department or went into gang life—meaning, organized crime. He was quick to add that he did not see any ethical difference between those two paths. Each was a route to a kind of power; for him and his peers, it was just a question of your personality. Did you prefer to be with the law enforcers, or with the law breakers? He had chosen to go with the crime syndicate.

He had done some jobs in Boston—about these, he never went into any detail. And then the Mob sent him to California. He worked as an “enforcer,” threatening, intimidating, shaking people down. He must have noticed that the word “kidnapping” shocked us. He took the time to give us the word-for-word definition of kidnapping from the California Criminal Code: “Moving another person a substantial distance, without the person’s consent, by means of force or fear.” He emphasized that the “substantial distance” required by the law could be small, like maybe 50 feet. He was hoping to retain at least some of our empathy, I guess. He wanted us to know that the kind of “kidnapping” he did (and we never learned anything further) was not like someone snatching the Lindberg baby and then driving away. He never offered a similar explanation for “attempted murder.” Nor did he ever deny he was guilty of any of the crimes of which he was convicted.

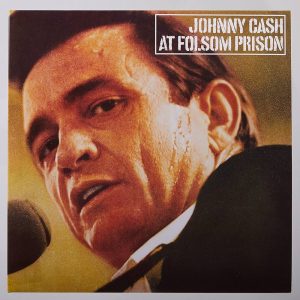

Bob’s happiest memory of life in prison was the day Johnny Cash came to Folsom Prison. He was in the crowd for the album that Cash recorded, called, “Live from Folsom Prison.” There is a nice re-creation of this scene in the movie, “Walk the Line,” the biopic of the life of the musician-singer-songwriter. That album was recorded in January 1968. In other words, the event was less than three years in the past when we met Bob. He had been in Folsom when I had been a freshman.

Bob had not experienced any struggles for social justice as a young man growing up in Boston or working as a mob enforcer. But he was incarcerated during the birth of the California prison movement, and he joined in some of the earliest struggles for dignity and justice behind prison walls. Among other stories of rebellious prisoners, he told us that he was involved in what he believed to be the first prison strike in California history. This was while he was housed at San Quentin.

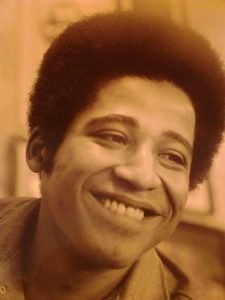

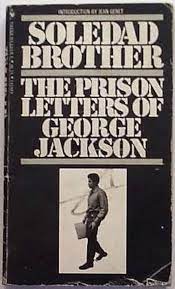

One of the main leaders of that strike, he told us, was George Jackson. Jackson had not been widely known outside the penitentiary back when Bob knew him, but he was by the time we heard Bob talking about him. Bob described him as “the most inspiring leader” he had ever met. Jackson was imprisoned with a sentence of one year-to-life after being convicted of an armed robbery of $71 from a gas station in 1960. His prison letters were published as the book, Soledad Brother, in 1970. He died in his eleventh year in prison, in August 1971—shortly before the Attica prison uprising– in what authorities called an “escape attempt.” Others credibly claimed that he did not attempt escape, nor would he have wanted to escape at that time, since his trial as one of the three “Soledad Brothers” was about to start and would provide an important public stage for his voice to be heard as he always wished.

The way Bob described it, there were separate leaders for the Black, the White, and the Latino prisoners, and each of them vowed to keep “their people” in their cells and refusing to go to their work assignments. He described it as a “pact to the death.” As one of the designated White leaders, he pledged to enforce the strike among the white prisoners or face death at the hands of the other leaders. (Inmates were easily able to make knives in the metal shop.) Similarly, the leaders of the other racial/ethnic groups put their necks on the line. George Jackson was the main leader of the Black inmates and was a big factor in keeping everyone united. Bob told us that all the prisoners stayed unified and they won some concessions as a result of their strike. I do not recall him spelling out any of these concessions, but other strikes during that same period (that one can research on the Web) focused on such matters as food, medical care, legal representation, visitation, and written explanations of punishments.

Bob had recently seen the news (as we all had) about the events that took place during the day of the supposed “escape attempt,” by Jackson. He told Claudio and me that he recognized the name of one guard who had been knifed to death that day. I haven’t forgotten his follow-up comment: “I hope they cut him end to end.” Bob described him as the kind of correctional officer who would come and talk to you in the recreational yard—or pretend he was having a conversation with you, even if you wanted nothing to do with him. “Then he would walk away from you, pull out a notebook from his hip pocket, and write down some notes, nodding his head and smiling toward you, trying to make it look like you had just given him some valuable information.” He would do this, Bob said, knowing other inmates were always observing. If his performance convinced someone that you were a snitch, “that was a happy day for him. And maybe the end of the line for you.”

As we sat there in those familiar dining hall chairs, coming to terms with the journey Bob had made was was a tall order I can only imagine how much he had to stretch himself to grasp and understand our trajectory.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Thanx Dale for sharing Bob’s story. Hearing Johnny Cash perform at Folsom Prison was indeed something special.

Did you stay in touch with Bob over the years?

I lost tough with Bob after I left Cambridge. However, I thought I heard his death announced on the radio some years later (maybe in the later 1970s). I didn’t know he was well enough known (or notorious enough) to be memorialized on the radio. I did my best to memorialize him here, in my own way.

Quite a story! I remember Soledad Brother and the prison movement well—you got a look deep into it via Bob, someone with a very different lived experience than you or me for sure. He must have trusted you to be so forthcoming. I wonder how his life trajectory went from there.

I don’t know about the remainder of his trajectory. But I think it gave him a lot of pride to have a bevy of Harvard and Radcliffe students, both undergrads and graduate level, cheering his words and his stance, enjoying interacting with him, and partaking of his culinary offerings.

What a fascinating story, Dale. You have given us great insights into the life of your friend Bob, his struggles from his Southie origin through Folsom Prison and the onerous parole system, as well as your own work on behalf of social and political justice in that era. Thank you for sharing and reminding us to read this past prompt.