On a hot August day back in 1979, my kids, ages eight, six, and two, were running in bathing suits through the sprinkler on my front lawn. Yes, they were likely fighting and screaming like banshees. That’s how we rolled back then. A tall African-American man in a suit approached me, reached out his hand, introduced himself as the incoming principal of Lincoln School, and handed me the start-of-school packet. My kids stopped screaming and stared. Who had ever heard of a principal who came to your house to meet you? I shared their amazement. When we walked to school the next week, there was Mr. Cherry standing outside the door in his three-piece suit, greeting children and parents alike with handshakes, high-five, and hugs. This was our welcome to what he called his “Love Boat” (yes, I am dating myself). And we happily got on board.

Warren taught me through example what it really meant to be a mensch, a good human being.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, Warren Cherry became my mentor as an administrator, educator, and community builder. More importantly, Warren taught me through example what it really meant to be a mensch, a good human being. During the first year of his tenure as principal of Lincoln School, Warren earned the trust and respect of the students, parents, and teachers alike by making himself available and approachable. He was more often found outside of his office in the hallways and classrooms.

Because Warren always made himself available, I did not hesitate to go straight to him with what I saw as a huge ethical dilemma. At that time, I was the PTA volunteer in charge of the Bookery, a school book store that enabled children to buy books for as little as 25 cents used or $2 new, and to swap books for free. As a lover of children’s literature who once dreamed of opening a children’s bookstore (this was during an era before these cozy places were swallowed up by Barnes and Noble), Bookery was the perfect volunteer opportunity. I got to select the books, display them, and help children make selections. But it was Warren who taught me what really mattered: getting a book into the hands of a child.

When I understood that having the book was what really mattered, I learned a profound lesson about educational priorities. In retrospect, I am so glad Warren was patient and respectful enough to hear my compliant. Because the Bookery was located in the foyer in front of the auditorium, it was easy for some students to steal books, hide them under the seats in the auditorium, and retrieve them on their way home. Once I caught on to this scam, I marched into Warren’s office filled with righteous indignation. How could I catch the perpetrators and stop them from what I saw as a gateway into a life of crime? While Warren made it clear that he didn’t condone stealing, I’ll never forget him saying, “There are far worse things to steal than a book.” His empathy for a child who had to steal a book to possess one taught me to overlook minor infractions and bend the rules if the result was good for children. Many years later, I invoked a version of Warren’s thinking as in my early days as director of Cherry Preschool. While I was aware of budgetary issues, I often decided to fill an opening with a child whose family could not pay tuition or to keep in school a child whose family owed us money. From Warren’s taught example, I learned that the needs of a child always trumped strict adherence to the rules.

Over the years my children attended Lincoln School, Warren taught me many other lessons about education and administration. He was a man who cared more about walking the walk than talking the talk. Following my stint at Bookery, I was PTA President, and by then I was totally enamored with his style of leadership. Warren created a true community in which staff and parents worked together on behalf of the children, his beloved “superstars.” He always had time for a warm greeting and loved to mingle with the children and chat up the parents. The man was truly amazing, serving on numerous community boards and actually doing hands-on work rather than just lending his name to the list of executive board members. Warren’s inclusive and generous model of community building informed my approach to being a preschool administrator. I learned more from his example than from all of the classes I took to earn a Master’s in Early Childhood Leadership and Advocacy.

Warren died on July 11, 1990, long before people shared almost everything with their online communities. But I am certain he would have been saddened by the way social media has profoundly impacted face to face connections. We are “virtually” connected to a huge number of “friends” (over 500 is not uncommon) and belong to many groups in which we share our most intimate thoughts with people we never meet. More time spent communicating via Facebook, texts, and Twitter means less time experiencing actual give-and-take, face-to-face time with family, friends, and neighbors.

Luckily for my children, they had a principal who was not glued to a computer screen analyzing data from the latest test scores. He was out there walking the halls, putting an arm around their shoulders, and even scaring them straight by delivering a loving lecture after they sat on his dreaded red bench awaiting discipline. His routine at assemblies was to call out, “1,2,3. I hear talking after 3.” This was generally followed by, “Ben, do you want to embarrass yourself in front of this fine student body?” The Bens never wanted to let Mr. Cherry or their classmates down, so they would immediately stop whatever behavior was disrupting the program. Love and respect. Hands on leadership. Knowing each child personally. This was the glue that bound Warren’s community of students, and bound so many of us to him.

The last time I saw Warren is etched in my memory as a true moment of grace, dedication, and professionalism. My kids had moved on from elementary school, but I was at a crossroads in my life. The preschool I had directed for seven years, the one all of my children had attended, was falling apart due to philosophical differences with the new minister of the church that housed it. I saw the writing on the wall and called Warren for some common-sense guidance. Should I go back to teaching? Did it make sense at my age? I had heard he had been ill, but he still came to work every day and told me to come on in.

When I walked into his office, I was shocked by how sick he looked. He was thin, pale, and coughing. Sadly, the rumor going around that something was seriously wrong with him was true. My impulse was to give him a hug and leave him be. How could he come to work in this condition? How could I come to him with such a trivial and narcissistic problem? Why did he agree to see me when he clearly needed all of his strength to get through the day? Out of respect for Warren, I stayed and asked for his advice. To have acted otherwise would have embarrassed him. As always, he listened with great interest and offered me practical advice. Wish I could remember what it was, but that really didn’t matter. It was his courage and grace that mattered. If he could do this, surely, I could find the strength to persevere and find a solution to my dilemma. Warren died a few months later, but the example of kindness and caring he set during our last encounter was all of the guidance I really needed. He was truly an unforgettable and very special person.

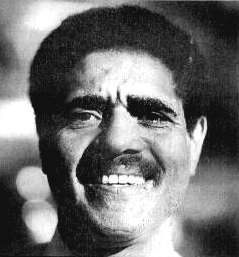

Warren Cherry in the background of a program I attended with my youngest daughter for her older sibs. He was always there.

This post is an excerpt from my book Terribly Strange and Wonderfully Real.

Boomer. Educator. Advocate. Eclectic topics: grandkids, special needs, values, aging, loss, & whatever. Author: Terribly Strange and Wonderfully Real.

Laurie, what a remarkable, kind, empathetic portrait you describe. Boston has a new superintendent who made the news this week for going door to door before school opened, particularly to the homes of those children who had the worst truancy record. I see a bit of your mentor in that gesture. His lessons on bending the rules a bit for the neediest children we could remember well in these days of teaching to the test and judging teachers only by how well the students do on standardized tests. I fear we are losing the common-sense touch and what used to wonderful about teaching in America. Your story reminds us of what we should be doing. Thank you for this wonderful example of a fine man.

Betsy, thank you for understanding why men like Warren Cherry were so important in education. Like you, I fear we have lost what really matters with the recent obsession with standards-driven education and teaching to the test. I have always seen teaching as a calling for the best ones. The way things are now, many of these teachers quit because they are discouraged from being creative and using their gifts.

Oh wow, Laurie, what a great story! And it’s an excerpt from your book! Now I will definitely have to get your book and read the whole thing. I note that his name was Warren Cherry, and the school you ran was called Cherry Preschool. Coincidence? Or was it named after him?

No coincidence, Suzy. We wanted to name the school for someone who exemplified the values of caring and community. I was really proud to name our school after Warren Cherry. Every fall, I take his portrait around to the classes and explain who he was and why the school is named for him.

I remember him so well … he was special, indeed!

Not too many principals around like him anymore.

I wish we had more people like Warren these days, Laurie, and your story clearly shows the reason he’s needed and what a great mensch he was!

Yes, I miss him and I think our schools miss his style of leadership/

Great story. How lucky to know such an inspiring and kind man.

Thanks! Yes, he was a very special person and I think about him all of the time.

Laurie, your profile gives credence to the beautiful reality that greatness does not need celebrity. I’m so often moved by people who do beautiful work for its own sake, without need for power and recognition beyond the boundaries of their own communities. Warren Cherry represents, thank the stars, the great army the real beautiful people. Thanks for this!

Thanks for reading my tribute and understanding the power of someone who humbly just did his job with so much grace. I’m sure he never knew how many lives he touched.