That summer of 1970, the family fractured. The postwar, white middle class nuclear family. Ours wasn’t too atypical. We had traveled, both parents worked; they raised three daughters stair-stepped two years apart, and sent them to college. Grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins were scattered from New York to California, and we weren’t close.

Our family culture was one of conflict avoidance. However, stories were told and opinions voiced over the dinner table, so there was no doubt about parental values. We were expected to become independent, and took it to heart maybe more than they realized. The biggest motivator was guilt. My mother was a legendary school teacher whose stern face and “I’m so disappointed in you” cut deeply—nothing more was needed. When our independence conflicted with their expectations, the lesson learned was: what the parents didn’t know, they were probably happier not knowing, and we were happier not discussing them.

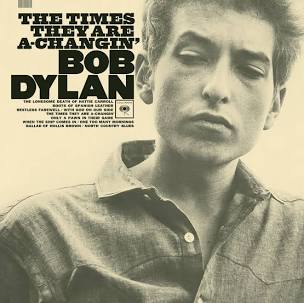

Dylan had it right—the times they were a-changing, as were the sons and daughters. Civil rights, assassinations, Vietnam, women’s rights, politics, sex and drugs and rock and roll, the generation gap. There were many times it seemed that everything important in my life fell into the “parents don’t really want to know” category.

Come mothers and fathers throughout the land, and don’t criticize what you can’t understand. Your sons and your daughters are beyond your command.

That summer:

Older sister—graduating college, decided to join the Peace Corps (ultimately stationed in Senegal).

Middle sister (me)—finishing two years of college which had included a university strike, march on Washington, bombing of Cambodia, ROTC protests, and endless political discussions and study. I was taking a year off after sophomore year, as even before entering college I had told myself (but not my parents) I would, to learn from the “real world”.

Younger sister—graduating from high school, lonely without her sisters and chafing at home, was hoping things would improve once away at school.

Parents—blithely thinking this summer would be a good time for family, booked a place at Bethany Beach for a few weeks. They had good memories of a summer there when sister #1 was a toddler. They didn’t consult the kids. And we didn’t tell them our plans either.

We all converged in Bethesda after respective schools were out. Surprise! Sister #1 was leaving in a few days for friend’s wedding in Michigan, then heading to the US Virgin Islands for Peace Corps orientation. Sister #2 was taking her meagre savings and leaving for the West Coast in a week. Ergo: No family vacation together at the beach.

The dashed expectations and conflicting plans created an eruption of emotion. Voices were raised, accusations made and tears shed—rudely rupturing our paradigm of polite non-confrontation, tapping into hidden resentments. It was a “scene”. We didn’t do scenes.

Sisters # 1 and 2 left. Sister # 3 spent a couple of miserable weeks at the beach where she and my mother spent a lot of time crying and wondering how everything had gone so wrong. The upheaval in the family seemed to mirror the upheaval in the world around us. Our nuclear family diaspora—inevitable but suddenly stark—was definitively underway that summer.

Epilogue: Family dynamics evolved over the years. Rapprochement of sorts occurred. Growth is painful. The kids, and parents, were alright.

The times certainly were a-changing, Khati, both externally and internally. Your ruptured family seemed to reflect the world around you. Your non-confrontational parents were so out of touch that they booked that nostalgic beach vacation without even checking in with their grown daughters (for so both of you were at that point in time), leaving the youngest in that tough position.

You describe your situation with the detachment that passage of years brings. I’m glad that time also brought rapprochement, of sorts.

Looking back, it seems even more poignant than it did at the time, though some of the emotion was due to the pain of knowing that things could not be reconciled, at least not at the time. We were living in different realities. Time and distance can help heal.

This is pitch-perfect, Khati, and thinking back, despite the differences in details, really resonates with my memories of that time as well. Didn’t it feel like the parents’ world view came crashing down around them? Our family took a slower path and had issues between 1971 and 1977, when I refused to move back home after college and my (younger) brother joined the Peace Corps. I guess it was those changing times.

Things were different indeed, sometimes hard to remember how much so. Glad to know I wasn’t the only one. I was determined never to move back home after graduating high school, and never did. Sometime in my thirties it was possible to recreate a relationship between us as adults.

That was quite a summer and quite a time to come of age Khati, for conflict and rapprochement, and taking stock , and now it’s good to hear the kids, and parents were alright!

Yes—quite a convergence of changes that summer, and in the end, we all muddled through successfully by many measures, following respective paths. It was “the end of the world” as it had been, but not the end of the story.

I love the way you tell this tale of generation gap, shifting expectations, and growing pains for your family. In 1970, the times were indeed changing and the Greatest Generation really didn’t get their boomer kids very well. I don’t think there is as big a shift now, but maybe I choose to look the other way when it comes to my kids.

I also have the impression that the relationships between generations then were far more fraught than today. Sometimes it is hard to explain how different things were.

Khati, this is a wonderful story, starting with the title which flips the famous opening line from Richard III. The family dynamics resonated with me, particularly the part about “what the parents didn’t know, they were probably happier not knowing.” I felt bad for sister #3, my position in my family, but at least she could look forward to leaving for college. Thanks for the Epilogue, telling us that everyone turned out alright.

That idea about not sharing with the parents what they didn’t want to know seemed to work—there are still many things I never shared, ever. They worried enough as it was. But there are some pretty good stories ha ha. Sister #3 also appreciates your sympathy!

Khati, I’d say you encapsulated universes in this perfectly circumscribed scenario, its volatile prologue, the gray distance of the assumptive unspoken slapped against the stark, black and white treasure ,of Dylan’s words, the harsh revelations at the climax, “oh, by the way…” and the sad disappointments of the dénoument. Oh what stinging papery hives we WASPS do weave!

You sound familiar with the dynamics. Glad you can appreciate the “assumptive unspoken”. It can be hard to explain to those unfamiliar with the phenomenon.

As Marian noted, Khati, this story is pitch perfect in all respects. And, though the facts in the foreground are very different, I can’t help but notice that the sumemr you write about was only one summer before the one I wrote about, and there was so much about the “a-changin” world at that time that permeated into all of our lives. (I’m also amused that your parents were talking about visiting Bethany Beach and I write about the summer that I moved from my hometown of Bethany. Granted, they are hundreds of miles apart, but still…)

And the epilogue is heartening without sugar coating things or denying the realities of imperfect lives in an imperfect world. Perfect.

Thanks for the comments—and who knew there was (sort of) a Bethany connection? One of the pleasures of “Retrospect” is that we can share these memories with others who have lived the same years and can appreciate the stories.

We did (and continue to) live in interesting times. You capture it so well here.

Have to agree. I think that is suppose to be a curse—“May you live in interesting times.” The peril we face is overwhelming and I don’t envy young people.