I spent my childhood and early youth in Littleton, a small Massachusetts town that had spent most of its previous two centuries clearing the forests and building the ancient stone walls that still sectioned off the fields. In the early 1950s, they were still milking cows, growing corn, peaches, potatoes, and apples. When my family moved there, its economy still depended largely on farming and essential work — carpenters, mechanics, storekeepers. A textile mill and a cement works offered the only industrial jobs.

After world war two, professionals began to settle in Littleton, but they largely commuted into Boston. The electronics and digital industries that moved in decades later were still only a gleam in their inventors’ eyes.

I attended a small, public school in the center of town. In good weather, I rode my bike, and later my motorbike to school, pedaling past woodlands and pastures and orchards, broken only occasionally by old colonial-era homes, a smattering of new middle-class structures, and the first housing development in town.

My father commuted into Boston and my mother stayed home. She had attended Reed College, and Cal Berkeley where she collected a graduate degree in social work. She went to work in that capacity for the city of Oakland until Depression-era cutbacks shrunk the city workforce. Then, at the age of 24, she lit out on her own for New York City where she worked as a social worker through the war.

In seeming contradiction to her education and adventurous spirit, she enjoyed our early years in the country as a mom and homemaker. The early 1950s was the time for that. As much as it drove my father crazy, she didn’t want a steady job or a career. I recall her saying she liked having her own front porch, a yard for us kids to play in, and a mailbox out front. We had all that.

My mother loved to talk. In the early days, the town still had a central telephone exchange that you called. There were no dial phones. When my mother wanted to make a phone call, she would pick up the receiver and gossip with her dear friend the local switchboard operator, Rozzie Schultz. This affable kibbitz session always ended with my mother remembering who she had intended to call.

It was through this switchboard clearinghouse that my mother first met Walter and Ezra. In summer, migrant workers came through Littleton and the surrounding farm towns, where they would hire on to cultivate and pick the truck farmers’ crops — the aforementioned corn, potatoes, squash, peaches, all the good stuff that the farmers sold at roadside stands. Every summer, Walter and Ezra would drive up from Mississippi to follow the early summer harvests, starting in the Connecticut Valley and working north. They would end up in Littleton where they found regular employment each year with one of the town’s oldest farming families.

Neither Walter nor Ezra could read. This made travel difficult. Road signs posed serious obstacles. Rozzie told my mother about the two laborers and their dilemma. My mother decided she would teach them to read, so she invited them to our home. I remember these two large, soft-voiced men, sitting at our dining room table in their freshly washed overalls. They would always bring a wrinkled paper bag of fresh vegetables: string beans, sweet corn or new asparagus and tomatoes. As the fruit ripened, my sister and I would each get a peach for each hand.

I loved sitting with them, eating those juicy peaches and answering their questions. Had I been fishing lately? Did my sister still climb trees? How deep is the ocean? How high is the sky?

Walter was the most talkative. Ezra would nod and agree with Walter and smile at his jokes and aphorisms, largely about the character and behavior of animals. I don’t remember any of the exact words, but I understood that for both men, animals had distinct personalities and even senses of humor.

My mother began with the alphabet. She found a portable chalkboard at the church and brought it home. Both men worked hard under my mother’s tutelage, getting their mouths around individual vowels and consonants, then identifying whole words. Toward the end of the first summer, she had them writing their names and spelling and writing words that they identified as necessary for navigation.

The next summer, Walter and Ezra returned with a third man, Josh. They called him “Josh by gosh.” Together, the two men had brought Josh up to speed over the winter. Under their fussy and watchful care, Josh recited a carefully rehearsed achievement test to show off his skills to my mother. She roundly congratulated Josh and thanked Walter and Ezra for their diligence. She was delighted!

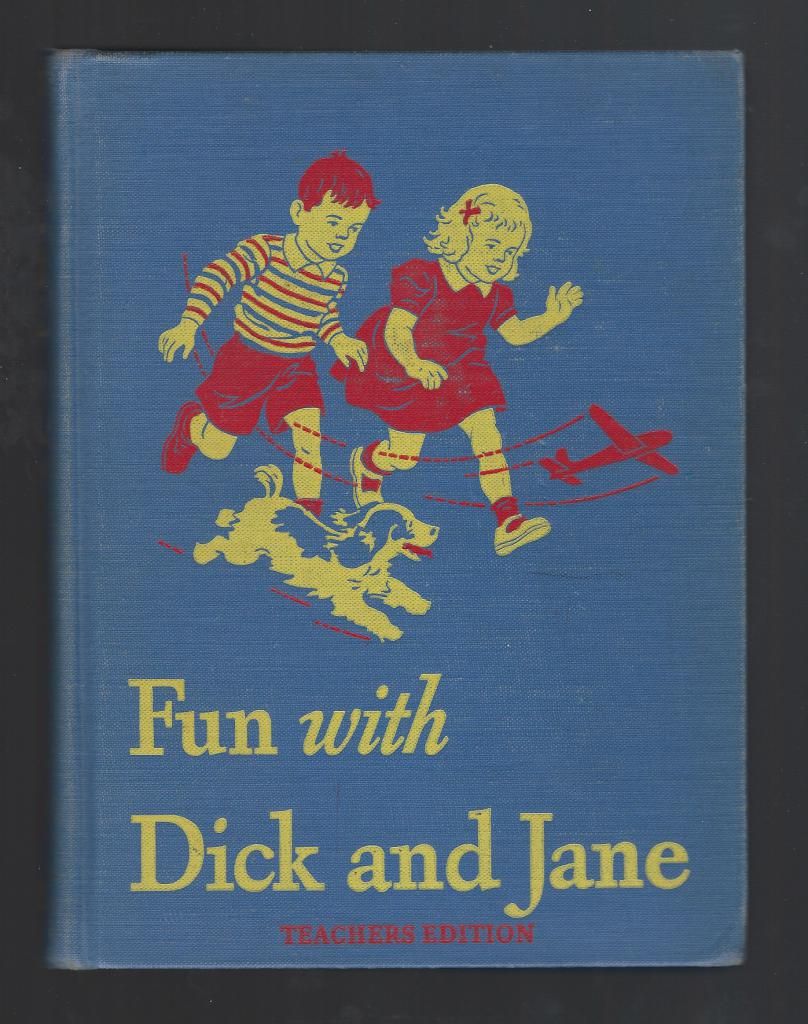

This summer my mother brought out copies of Fun With Dick and Jane and got the men reading. I wanted to help them. I was a strong reader and by the second grade I was running a reading group for Mrs. Hastings. My mother shook her head with a definitive “no” and frowned at me when I first corrected Ezra on a word. She later explained to me that it might be embarrassing to them to be guided by a child.

That summer, Walter, Ezra, and Josh left early. They were driving up to Maine for the potato harvest. We promised to see each other next summer and watched them climb into Walter’s giant old pre-war Chevy sedan and motor slowly off, trailing a blue line of exhaust from the tailpipe.

June came. I had finished third grade and was ready for a summer at the nearby lake complete with swimming lessons and first aid classes. My mother was prepared for the men’s return but they never arrived. That fall, we heard as a “by the way” from Mister Kimball, the farmer who had hired the men each year, that Walter and Ezra had been killed in an automobile accident.

When I heard the news, I remember a hollow, aching feeling expanded behind my eyes. I had not ever experienced the death of someone I knew. I sat by my mother at the table while she drank coffee and quietly cried until my father returned late from work and the long drive home.

# # #

I began this story in response to last week's "volunteer" prompt but quickly realized I was generating a Retrospect twofer.

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

Such a beautiful, sad, tender story, Charles…an awakening, an opening, a slam. Very moving. Thank you.

Thanks, Barbara. Sorry for the slam. It’s probably the last thing any of us need right now. Maybe I’ll rewrite it as per Suzy’s suggestion :-)!

Heck no! I love it as is…we’re all adults here. We don’t need to tie things up with pretty bows. Please, don’t change a thing!

Gotcha, Barb! Thanks!

Wonderful story, which you alluded to last week in your comment on Betsy’s story. Covers both spelling and volunteering. I loved it until the oh-so-sad last two paragraphs. In my version, Walter and Ezra would survive and thrive!

Thanks, Suzy. I, too, felt bad about the bummer ending. Maybe I’ll rewrite it along your suggested lines!

Apparently Barb thinks we’re all adults here. 🙂 So I’ll just have to write my own version to satisfy my inner child.

Haha, good one, Suzy. Of course it’s up to each of us to be childlike, childish, ecstatic or sad. I’m just grateful for all of our camaraderie.

This is so evocative all the way through, with the naming of the crops being raised, the men being characterized individually rather than lumped together. You give us an “establishing shot” of the town and the economics and the previous history of your mother, as in a movie, and then zoom into the individual lives (including your own) that take center stage. It’s just a very finely realized piece, including the emptiness when the men are killed and the physical/physiological description of what it felt like to personally know someone who had been taken from the earth.

In my version, I was just hoping that Josh would reappear…

Thanks so much for your perceptive reading, Dale. Much appreciated. When Josh wraps up that hassle in Jericho, I’ll get him back to Littleton.

This is a stunning piece of writing, Charles; evocative of time and place, long gone. “Fun With Dick and Jane” brings back my childhood too, but using it to teach adults is an act of courage and faith for your mother. And how perceptive and kind that your mother won’t let you, an eager child, help the adults with their reading.

Though the location and timeframe are different, this brought of moments of “To Kill a Mockingbird” with Scout and Gem not quite understanding what and “entailment” was, but welcoming Walter to their table, even though he douses everything in syrup.

You paint vivid pictures of the migrant workers, from the smell of the work clothes, to the eagerness, commitment and pride in learning to read. And the mournful loss when they do not return. Please do not give us a happy ending. We need the truth, even now.

Thanks for your reply, Betsy. I always feel as if I’d done something right when I elicit such thoughtful comments. I won’t change the ending. I do think it’s an important time in any person’s life when they first experience the loss of someone they know. I loved that detail about “Mockingbird’s” Walter and the syrup!

What a poignant memory, Charles, as well as a beautiful portrait of your mother. Spelling and reading lessons became a tragic life lesson.

Thanks, Laurie. I enjoyed writing up the recollections of my mother’s place in the cosmos. She left a footprint beloved by many.

So evocative of that era, Charles, your story took me immediately to your mother’s table and her teaching those men. How sad an ending, but how heartwarming the effort was. I can relate to running a reading group, and by second grade I was assigned to help my grandmother Rose, who could not read or write English, with correspondence and language tasks. She was so shy outside the home because she was embarrassed, but I loved helping her.

Thanks, Marian. The reading lessons brought these two (then three) striking men into my life at a time when I knew so few people from different worlds. They were unforgettable, as was my mother’s attention to them.

Lovely bittersweet story and memory Charles, and bless your mother.

It came out very easily. One of those recollections that sits deep down like an embryo for ages and then, once called, swims to the surface and takes shape.

Yes Charles, that happens to me too when Retro prompts!