My parents were married for 68 years. During all of those years, my father’s time in the army was never discussed, and yet they kept the letters. After they both had died, the shoe boxes filled with their World War II correspondence sat in my basement, my inheritance and guilt trip from my mother. She often told me that when she died, I would have the privilege of reading these “love letters.” Mom died in April of 2015, and the boxes remained unopened for over three years until I was ready to look at them. When I did, a couple of family myths were debunked.

Now that my parents are gone, I realize there were so many questions I wish I had asked them. All I have now are their letters to fill in the gaps in my knowledge of the years between when they met and their marriage.

My parents’ lives during the war were always a mystery to me. I knew that they met in May of 1941, just before Mom graduated from high school. She often shared the story of how they were introduced by mutual friends. How my father didn’t even walk her to the bus stop after their first encounter. How he violated the three criteria she had at that time for good future husband material: He was not three years older than she. He was not tall. And worst of all, he was not a good dancer. But he was persistent and, as she described her feelings, he grew on her. Despite his not fitting into the myth she had of a perfect guy, they were engaged on November 25, 1942, the day before Thanksgiving. She was nineteen and he was twenty-one. And then the part of their story they shared with me ended.

I knew they were married on January 30, 1944, but they never talked about those years between their engagement and their wedding. Obviously, World War II was raging then, but my father never shared how the war impacted him other than to say he was drafted but never saw combat.

Now that my parents are gone, I realize there were so many questions I wish I had asked them. I guess this is a pretty universal phenomenon. All I have now are their letters to fill in the gaps in my knowledge of the years between when they met and their marriage. Because they wrote daily and their missives often crossed in the mail, their letters are more of a window into their separate existences than a back and forth correspondence, and they reveal the secrets my parents never discussed with their children.

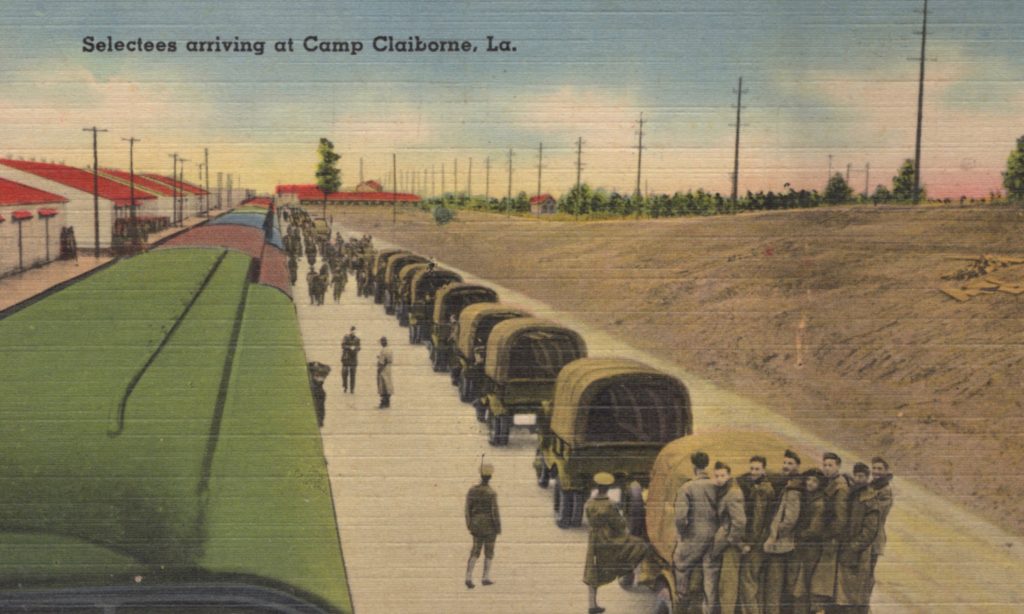

After he was drafted, Dad was sent to Camp Claiborne in Alexandria, Louisiana for basic training. He arrived there via train by December 14, 1942, so he must have left shortly after my parents became engaged. His initial reaction was fairly optimistic. The weather was warm instead of the winter temperatures he left behind in Detroit. He had been selected for the Signal Corp based on scoring high on a written exam and was hopeful he would become an officer. He wrote, “So far it’s been really fun.” He was referencing the train ride, complete with dice games and the “funniest characters” he had ever met. The weather was glorious, the camp had three theaters, a large gym, and a USO club. His letters almost sounded like he was on a vacation.

In these early letters, Dad called my mother darling, sweetheart, dearest, honey, baby, wifey, beloved – not the father I knew at all. He described increasing drills, marches, chores, and numerous inoculations, and warned her he might not be able to write every day as the demands on his time were increasing. By December 19, his enthusiasm had dropped, as the reality of army routines and expectations hit home. He was trying to learn Morse Code, and he still hoped to become an officer so he didn’t have to take orders from “inferior jerks.” Now that does sound like the father I knew.

Perhaps the trauma of the war years accounted for the silence that accompanied them. Like many members of the Greatest Generation, my parents rarely shared much about their experiences during World War II. There were a handful of stories, particularly of my mother’s train journey from Detroit to Alexandria, Louisiana in the company of her future mother-in-law to visit my father when he was in basic training. There were photos they had sent to one another, and photos of my father’s furlough in April of 1943. When I finally decided to read what Mom called Dad’s love letters, I uncovered some things that dispelled myths that had been handed down from my parents.

My mother told me many times that their marriage date was decided by her parents, who insisted her older sister should get married first. Making my way through over 300 letters my parents wrote to one another during World War II, I felt both like a dutiful daughter fulfilling a promise to her mother to read these letters after her death, and like a spy uncovering information that contradicted the narrative I had always believed about my parents.

Clearly, once the excitement and patriotic fervor wore off, Dad was feeling lonely. As the pampered first-born son, his mother had catered to his every need. The army, not so much. By New Year’s 1943, Dad was depressed and missing Mom terribly. To stave off his unhappiness, Dad hatched the “marry me” initiative. Perhaps he was insecure about Mom’s loyalty and love for him. Although she wrote every day and he intellectually knew the mail service was unreliable, he complained about not receiving long, daily letters from her. His letters were filled with florid passages about his love for his future wife. He decided that they should get married when he came to Detroit on furlough and even chose the date of April 18, 1943, for what he thought would be a simple ceremony performed at home with close family in attendance. To understand the pressure my still-teenaged mother was under, you would have to know this about my father. All of his life, he was a relentless debater who would argue his point endlessly and never concede or compromise. Thus, he badgered Mom about getting the marriage license and blood work done for their furlough wedding.

In early March, 1943, Mom and my paternal grandmother took the train to visit Dad. This is the part of the story I know. My mother had wanted to visit by herself, but Dad worried about the rivalry that already existed between her and his mother. Just before the visit, he wrote, “After all, honey, even though you come first, I am quite lonesome for my mother also.” For a week of Mom’s three-week visit, Dad was hospitalized with the measles. At this point, my father still had plans for advancement that included applying to the University of Chicago Army Meteorology School, getting the army to send him to college for courses leading to a technical position, or being accepted to Officers’ Training School. None of these scenarios mentioned combat. But his path was already uncertain at this point, and it is unclear how he thought Mom would fare as his wife, living in a strange city on her own with occasional overnight visits from her husband and finding a job that paid $15/week.

It turned out my mother was the one who nixed the furlough wedding because she wanted to be practical. They were in debt and she wanted to save money first. Being nineteen, she also wanted a real wedding. She reassured my father that she loved him and wanted to marry him, just not right then. In one letter, Mom confessed that when she was with Dad, she easily fell under his influence and agreed with his ideas. This was true for all of their 68-year marriage. But on her own and apart from him, she was able to make a pragmatic decision. She wrote, “These last few days have been a living hell for me as I’m so afraid you won’t understand.”

She was right about that. Dad’s airmail special delivery response was bitter. He threatened not to come home on furlough. His letter was peppered with negative thoughts. His final remark before coming home on furlough was underlined, “Don’t disappoint me in this.” In a letter in response, Mom told him, “Don’t sulk like a baby.” It was probably the last time she stood her ground in their relationship.

My father spent a total of ten months in the army in 1943, the height of World War II. The letters he wrote to my mother after his April 1943 furlough reflected his disappointment over not getting married during the furlough and depicted a downward spiral during which he described himself as pessimistic and in a “miserable condition not knowing where or how to squirm out of it.” This is the story he hid from his children, only revealing a few details near the end of his life. He would have benefitted from psychological help because, clearly, he was anxious and depressed. He was classified for limited service due to stomach trouble noted on his draft physical. By May, in his letters to Mom. he called himself “a washout” and a failure who was not suited for army life. He felt he had the wrong temperament and was deeply ashamed of himself. Instead of being in the Signal Corps, he became a clerk in the radio school. His “nervous stomach problems” were back again, due to his “general disgust” with things and what the doctor diagnosed as a “nervous condition.” Confined to quarters, he was very bored and depressed. He felt like “a round peg that refused to go into a square hole.” At this point, he was pretty sure he would be reclassified for limited service and begged Mom not to tell his parents.

By June, Dad was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of his stomach problems. Hospitalized soldiers had nothing to do other than loaf around, read, pitch horseshoes, and play ping-pong, while they waited to go before the reclassification board at the end of their hospital stay. My father spent over two weeks in the hospital during which he received no treatment for his stomach or emotional problems. He was on a ward for men awaiting discharges. His letters from this period were short and mostly consisted of complaints about boredom and effusive proclamations of love for mom. He was “peeved” at himself because he couldn’t adapt to army life. Yet, he was annoyed with Mom for saying she would regard a discharge as good news. At this point, Dad was highly ambivalent about receiving a discharge.

Despite what my father called his “jittery nerves,” the review board turned him down. His doctor asked for a second review, but Dad was returned to his unit in late June, still complaining of stomach pain and telling Mom, “my nerves are shot.” He shared that he couldn’t eat or sleep and was feeling “lowdown” and disgusted with himself. His letters reflected his depression and feelings of worthlessness, doubt, and misery. Again, he described himself as “a complete washout,” jittery, jumpy, and ashamed. He went back to being a clerk at radio school and doing what he described as “dirty work.” In these letters, he shared his worry he would fail at everything in life. Quite a heavy burden for his nineteen-year-old fiancée to bear alone, as she was sworn to secrecy and could not share this with his family or hers.

My father continued to look for a way to transfer to something more suited to his interests and talent. He went to his commanding officer and got an application for the college training program as well as for a job as a supply clerk. His college choices were engineering, personnel psychology, and languages. Interestingly, he would have picked psychology as his first choice but it was closed at the time. Perhaps this reflected his suspicion that he had emotional issues to work out that were the underlying cause of his symptoms.

By August, Dad wrote about rumors that his unit would leave Camp Claiborne, go on maneuvers for three months, and end up in California. Another rumor suggested the army would cut 100 men from the company and ship them elsewhere. For reasons that don’t make sense to me, Dad turned down a transfer to supply because he felt he was better off sticking with what he knew. His company went on a three-week training mission during which he drove the supply jeep. By early September, Italy had surrendered and Dad was hopeful the war would end soon. Then disaster struck. Instead of going on the three-month maneuvers scheduled to begin September 15, he wrote my mother on September 19 that he was back in the hospital and had been cut from the Signal Corps before the maneuvers.

My father’s war ended quickly when he was told to take an overseas physical exam. As he described it in a letter to Mom, he “got excited” and his blood pressure skyrocketed. When the doctors couldn’t calm him down, they recommended he be discharged and sent him back to the hospital. In a series of letters written in September, 1943, he described lying around for days on end, bored, disgusted, on edge, and discouraged. His ten months in the army had “amounted to constant frustration, failure, and discouragement.” At the end of September, he had to appear before the review board again. This time, the ruling was an honorable discharge.

Dad left the army on October 11, 1943 so there were no more letters filled with his hopes, disappointments, and flowery proclamations of love. Back in Detroit, he and my mother planned the wedding she had hoped for, and on January 30, 1944, they became man and wife. I know this outcome did not lead to a happier-ever-after ending, at least not then. Dad went to a therapist who kindly saw him for little money. His dreams of a college education were transformed into attending accounting school and becoming a CPA, a job he loathed. On September 7, 1945, his first child was born. She was an accident. She was me.

During all the years of their long marriage, my father’s time in the army was never discussed, and yet they kept the letters. There are many photos of my mother’s visit in March, 1943, and my father’s furlough the next month. The myth perpetuated by these photos was one of happiness. After I read their letters, I saw things differently. I knew how my father’s army journey ended because, near the end of his life, he explained that he was honorably discharged due to extremely high blood pressure and anxiety. This was so shameful for him that he never spoke of it before then, leaving me to wonder for most of my life how he was a civilian by 1944 and my father by 1945.

My mother made me promise to read their war correspondence after they were both gone. Although she called them love letters, I think she wanted me to see two truths that had been hidden when they were alive. The first was the myth that she put off their wedding because her parents made her wait until her older sister married. The second was my father’s anxiety and depression that made him unfit to serve in World War II.

I invite you to read my book Terribly Strange and Wonderfully Real and join my Facebook community.

Boomer. Educator. Advocate. Eclectic topics: grandkids, special needs, values, aging, loss, & whatever. Author: Terribly Strange and Wonderfully Real.

Very touching story, Laurie. I can imagine how frustrating it must be that you never had the opportunity to ask them about the things you learned from the letters. I love all the photographs of them and the postcards that your father sent. The letter and envelope you used as the featured image were fascinating – the US Army stationery, the very neat cursive, and the envelope with the word “FREE” instead of a stamp. Thanks for sharing all of it!

Yes, getting through all of those letters was quite a journey. I wish my father hadn’t felt so much shame about what was clearly severe anxiety and depression. I must say that I gained more respect for my mother’s ability to handle all of this at such a young age and to hold out for what she wanted.

Amazing, Laurie, how your parents hid crucial information about their experiences, but as you write, that seems typical of the Greatest Generation. My father was in the navy toward the end of the war, and like you, I didn’t ask a lot of questions that would occur to me now, such as how he could function in cramped quarters below deck when he had bad claustrophobia. I’m glad you did read the letters because, even if painful, they opened a window into your parents lives.

Yes, Marian, I think knowing is always better. I didn’t think less of him but rather understood him much better. I also wonder how much his self-esteem would have been improved if he could have shared his experience and made peace with it. Ironically, he thought my husband and brothers should have embraced being drafted during the Viet Nam war. He didn’t understand the protests over serving. I’m guessing his time in the army was so shameful to him that he repressed it for most of his life.

What a compelling story, Laurie. Good for your mother for insisting that you read those letters to learn the truth after both your parents were gone. But sad that the pretense had to exist for so long that these were “love letters” and why your father was discharged from the service. I’m sure it was a difficult task to get through all those letters, but ultimately revealing and rewarding to finally see the truth laid bare. The photos are wonderful. Thank you for taking us along on your journey.

Thanks, Betsy. I think she wanted me to know these things but couldn’t bring herself to tell me.

What a moving story, Laurie! Your compassion for and understanding of both your parents is palpable. Once again I’m struck by how our generation is so much more open than our parents’ generation was — as evidenced here on Retrospect. There were a LOT of secrets, or things that just weren’t talked about. Many of us do have written correspondence and photographs, on paper, that we can pore through, like detectives, should we decide to piece things together — 300 letters, wow! — which (sadly?) OUR children WON’T have, but I think a lot of us grew up determined to be more communicative than our parents. I think we’ve succeeded. What a journey you’ve been on, Laurie — your mom and dad would be proud, and deeply touched!

I hope you are right about them being proud of my writing about their myths and secrets, Barb. While they never shared much about their feelings or personal experiences, you are on target about them leaving their letters behind. I hope I have told my kids enough to understand my life, but they can always read Retrospect (LOL). I’m also eternally working on my memoir pieces in my writing group. Maybe they (or my grandkids) will read those?

Laurie, what a bittersweet time you must have had going through those letters.

When emotional problems were considered shameful as they were then, people suffered needlessly all the more.

At least now we have a better understanding of mental health issues and there are available treatments.

Every family has such stories, I’m glad you shared yours.

Thanks, Dana. Even though my husband of 51 years is a psychiatrist and my father knew he would understand, he could never bring himself to share this story. I also had an uncle who was bipolar and would “disappear” for months at a time in psychiatric hospitals. No one ever explained where he was. It’s sad.