One of my favorite read-aloud picturebooks during the time Anissa was in my day care class

I was at my desk in 1987 in a third-floor office I shared with another researcher in a stately old building called Cheever House when a call was transferred to me from the front desk downstairs. The house was off the Wellesley College campus but owned by the College; it housed the Center for Research on Women. “This is Dale Fink,” I pronounced into the mouthpiece of the dial phone on my desk.

Was it that kind of child-centered activity that made Anissa look back on that time, and on me, with such fondness?

“Hi.” There was a pause, as if she thought I might be able to recognize her friendly voice after having spoken only a single syllable. The young female voice then continued. “It’s Anissa.”

Anissa? My life had included only one Anissa. I was now in my late thirties, and the Anissa I knew had turned five years old during the year she was in my day care classroom in Dorchester, a multi-racial section of Boston. I had been in my twenties then. Let’s see, that would make her about 16, turning 17 this year.

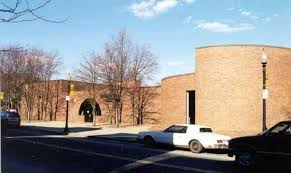

Anissa was one of the kids in my class the year the city of Boston was building the new library in Codman Square, the part of Dorchester in which we were located. While my teaching teammates engaged other children in different activities, I would often bring a small group of four or five children to take a walk and settle down outside the construction fence with paper and markers and draw what they saw while we chatted about it. I would annotate the drawings with comments they made. Some of them made very elaborate representations of the equipment, tools, men up high on partially finished roofs, and impressively well executed images of men carrying lunch pails. Eventually, we assembled the pages, stapled it together, and some of us went down and showed our finished book to some of the men on the construction crew during their break time. Anissa was one of the more confident kids in my class that year, very verbal and outgoing. I bet she was one who insisted on coming along on that trip that I had arranged that same morning by stopping by the construction site early and finding a supervisor to approve my idea and make sure we would be safe.

“Anissa?” I then repeated it, this time adding the last name of the cheerful, energetic, undaunted girl with large brown eyes that I was remembering. “Anissa who was in my daycare class when I was a teacher at Wesley Child Care Center?”

“Yes! You do remember me! That’s so great! ‘Cuz I’ve always told my mother that you were my favorite teacher.”

“Of course I remember you—it’s so great to hear from you. How did you even know how to reach me?”

My mind was racing to recapture more scenes of our time together. What images were cemented in Anissa’s mind from that long ago childcare classroom that led her to such a happy conclusion? Were our circle-times etched into her memory as they were into mine? Instead of taking attendance, we always started circle-time by offering everyone a chance to announce their presence with a creative gesture or sound. For instance, “when I call your name, beep your horn.” From our 18 class members seated on their individual carpet squares—all from lower income families, including white, African-American, Jamaican, and Haitian–there came a quick round of toot-toots and beep-beeps and honk-honks that ranged from high-pitched and squeaky to blaring and raucous.

“My mother said I should be able to find you, if I called up Wesley Day Care. They knew you went to work at another place after you left there, and so I called that place,”

“You mean N.I.C.E. Day Care in Jamaica Plain? You called them?”

“Yes.”

“And they knew where I went next?”

“Yes, after that was Driscoll School in Brookline.”

“Right, I was the teacher-director for the Extended Day afterschool program there. And they told you I ended up here?”

Maybe it was the singing that she loved. We used traditional songs, like the hokey-pokey and “What can you do, Punchinella, funny fella?” allowing children to get up and move around. But we also sang civil rights songs, such as “Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around,” and “This little light of mine.” We adapted the latter song by letting kids take turns telling us where they wanted to shine, so it was “all over Dorchester” or “all over Mattapan,” or “all over my Grammy’s house,” or “all over Franklin Park…I’m gonna let it shine.” Could Anissa have memories of the fun we had singing together?

“Yes. I told my mother there was no way I was going to find you, but she said just try. I can’t believe I am talking to you now!”

“Well, this is great, Good for your mother for encouraging you. You were always a great kid, I can’t wait to find out what you’re up to these days, what’s going on in your life. But before I start asking you a lot of questions, I guess you had some reason for finding me—so what was it?”

“I just wanted to talk to you.”

Did Anissa like the way we conducted our nap time? I had started out in younger classrooms in that same center, and so had she. She would be aware—without having the diction to name it–that in other classrooms, there was a martial atmosphere during naptime, Given a staff that lacked background in early childhood education and with a starting wage when I began in 1972 of $100 per week gross (but only $87.50 until you got through your 90-day probationary period), my nonprofit employer could not realistically be on the market for well-credentialed professionals. In spite of that, most of the teachers managed to improvise an abundance of meaningful activities, But naptime could be hellish, as teachers forced everyone to stay on their cots, many unhappily, for 90 minutes, and some even threatened to withhold snack after naptime from anyone who was disruptive.

Location of my day care classroom that Anissa attended, in a Lutheran Church near Codman Square, Dorchester

My co-teacher and I, occupying a satellite space in a church away from the main center, created a radically different plan: Rest quietly for 30 minutes. A bell on a kitchen timer will sound at that point and anyone who is still awake and who has respected the quiet time may either choose a book from the library corner and bring it back to her cot, or come to a table and enjoy quiet activities, such as playdough or bristle blocks. Once we removed the elements of threat and coercion from naptime, we had more children sleeping peacefully and for longer in that classroom than in any other I had experienced. The children who could not or did not need the sleep relished the new freedom and the special materials we purchased that were only brought out at that time. I doubted that Anissa could remember these kinds of specifics that made our classroom different from others, but I hoped that she looked back on it as one that was all about supporting children, not policing them.

“You wanted to talk to me? That’s wonderful, but for any particular reason?”

“You’re my favorite teacher I’ve ever had. Partly because of you I’ve decided to apply for early childhood education. I’m a junior, starting to look at colleges and I was telling my mother I wish I could talk to you. But I figured there was no way to find you.”

At last, I felt I had found the secret code that unlocked the reason for this unexpected phone call. “Oh, Anissa, that is so great that you want to go into early childhood education, You would be wonderful as a teacher for young children. So that’s why you thought of calling me, so I could help you think about places you could study for that field?”

She seemed startled–even offended–by my interpretation. Suppressing a laugh, her voice got louder. “No–o-o-o! That is NOT the reason I called you. Sure, if you have ideas for me, great. But I just told my mother I wish I could talk to you and tell you that you’re the best teacher I’ve ever had,”

Did she remember “Congratulations, mistakes, and suggestions?” This was something I adapted from a friend who taught early childhood education alongside a Marxist educator in Mexico. It was the main agenda for circle-time every Friday, and when my co-teacher and I first initiated it, it ended in just a few minutes, because children of ages four and five were not accustomed to providing feedback to their peers in a non-punitive environment, in which we encouraged everyone to listen and not to judge anyone as good or bad. You were supposed to try to think of a specific action during the past week by one of your peers that you thought was worthy of praise (e.g., “congratulations to Courtney”) and also an action from the past week you viewed as undesirable (“a mistake by David”). If someone congratulates you, don’t thank them. Just listen. If someone said you made a mistake, don’t try to explain yourself or apologize. Just listen. After a couple of months of this weekly activity, they started to develop confidence and accumulate mental notes they wanted to share on Fridays. We had to set strict limits on each person’s time and keep it moving or we would have been stuck all day on our carpet squares. Was it that kind of child-centered activity that made Anissa look back on that time, and on me, with such fondness?

I did not find out what specific memories Anissa carried with her from that child care classroom or about me as her teacher. But I knew that, without using the words “thank you” at all, Anissa had offered me the greatest expression of gratitude that I could ever hope to receive.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

I can’t imagine a more rewarding thank you, Dale.

Wonderful Dale, I wish we could clone you and put a Dale in every early childhood classroom! Thank you!

So much of what you describe in very familiar to me. We encouraged the same type of drawing and dictation, sang the same songs. And you are so right. There is no greater gift for a teacher than a thank you.

Great story, Dale, and a general thank you for your excellent strategy regarding nap time! I was one of those kids who didn’t need to nap but fortunately had the patience to stay quiet on my little woven rug. As an adult, when I worked at a company, I saw parents crying because their two-year-olds were expelled from day care because they couldn’t stay quiet during nap time. You are to be applauded.

Thanks, Marian. Even in better-funded centers with more qualified staff (and for that matter, even in the public schools) there is still a tension between “policing” children and supporting their growth and development. I lived through a lot of both in my years working with young children.

It must have been thrilling to receive that call, Dale. No better reward to be told (even implicitly) “thank you” from a student, and know that you shaped her life in a positive way forever.

That call was even beyond thrilling! I was floating around for days afterwards.

This is a lovely story, Dale. I’m so glad that young lady found you before too many years had passed. I tried to find one of my junior high school teachers to say “thank you”, but I waited too long. I found him, but he had passed away. I so regret not searching for him earlier.