Eight years ago this April, I spent a couple of months with my father as he was waiting to die of acute leukemia. We shared old stories and tried to capture a couple on paper or tape. There was one that he had partially written up, using old newspaper clippings and notes, about religious riots in East Pakistan in 1963-64, which tapped into a long history of divisions including the blood war of partition of 1947. The riots happened while I was away in boarding school, but I certainly knew the people and places. He wrote about how the Muslim staff that worked in our house protected the gardener and his Hindu family with our help, temporary refugees in their own land. It is a story of intolerance, fear, and hope.

The Muslim staff that worked in our house protected the gardener and his Hindu family, temporary refugees in their own land.

My sister and I edited the story during those last days, but the writing is mostly my father’s and I haven’t changed much. It is a bit lengthy, but if you are curious, I hope Retrospect doesn’t mind my sharing it here.

Dacca story

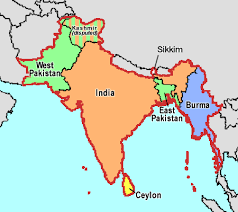

On December 27, 1963 a sacred relic said to be hair from the beard of the prophet Mohammed was stolen from the Hazaratbal Mosque near Srinigar, the capital of the Indian-held portion of Kashmir. The hair had been kept in a silver glass tube behind a locked door in the mosque, and had remained there for 300 years. Four days after the reported theft, on December 31, a thousand Muslims marched through Karachi protesting the disappearance of the relic and condemning India for the loss.

Muslims then took two Hindu idols from a temple in India in what was a retaliatory move for the theft of the hair. Muslim protestors marched in Srinigar and in Karachi, the capital of West Pakistan. They expressed sorrow and anger, appealing for Islamic solidarity, with the slogan, “let us fight in Kashmir”. There was an appeal for a complete shutdown of Karachi, but this failed.

On January 12, Premier Kwaja Shansuddin of Kashmir announced that the sacred hair had been recovered by Indian intelligence officers. In Srinigar, there was rejoicing by Muslims; Hindus embraced their Muslim friends and expressed happiness. The theft had led to the suspension of all normal activities in Srinigar, and there had been daily processions of outrage in Pakistan. In the Indian capital of New Delhi, there was relief that the crisis had blown over.

This was not the end of problems, however. Before the recovery of the relic, there had been anti-Hindu riots in the Jessore and Khulna districts of East Pakistan. Several hundred Hindu refugees crossed the border from those towns and spread word of the anti-Hindu violence there. Muslims made up 20% of Calcutta’s population at the time, and were now made targets of anti-Muslim violence. By January 9, retaliatory demonstrations had broken out in Calcutta, India. Hindus there attacked Muslims and looted Muslim shops. Hundreds of protestors, mostly students, marched in Calcutta against the Pakistan Deputy High Commissioner and burned an effigy of Ayub Khan, President of Pakistan. This was initiated by Hindus from the poorest part of the population, many of the refugees or children of refugees who came from East Pakistan after the bloody 1947 partition of India. Indian papers appealed for peace, remembering the million or so Hindu and Muslim lives lost in the terrible riots following partition.

Calcutta imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew in parts of the city. Police clashed with demonstrators and shot one student dead. There was panic and unrest, and at least half a dozen people were stabbed in isolated incidents. All told, 60 people were killed in Calcutta over three days, and there were 50 cases of arson, mostly from police action. Three policemen were killed after ordering a Hindu mob not to attack a Muslim village near the East Pakistan border. Army units moved into Calcutta the afternoon of January 11 to reinforce city and state police, who were swamped by the spreading lawlessness.

This sort of reciprocal rioting made its way across India in those early days of January and by the middle of the month, East Pakistan was also tense. On January 15, even though the sacred hair relic had been recovered, there were reports that police had fired on rioters in Dacca, the capital of East Pakistan.

At that time, our family was living in Dacca, where I was part of the Ford Foundation-financed effort to assist the Pakistanis in putting together economic development plans. My wife, Lyn, was acting as the Headmistress of the Dacca American Society School. Our two older daughters were away at school in Europe, but eleven-year-old Susan remained with us in Dacca. We employed several servants, including the stout and jovial cook, Jaharbux, the more serious and proper bearer Kabat, and a gentle young man named Mohan, who was the gardener.

As these first reports of disturbances in Dacca were received, the American school was closed. The team on which I was working continued to meet with government officials however, and we were able to get a more informed picture of what was going on than might otherwise have been possible.

One of our close friends, Bobby Barr, was an official with the USIS (United States Information Service) and was traveling. He telephoned from Chittagong, a seaport on the Bay of Bengal, to advise that he was leaving town and wanted to be met before entering Dacca because of stories of rioting around the trains going through East Pakistan. I was able to do this and met him at a railway station called Tongi, just outside of Dacca. Bobby had stories of mobs entering the trains as they went from station to station, looking for people who had not been circumcised, as this was a way of identifying whether people were Hindu or Muslim. Those who were Hindu were summarily dispatched on the station platform.

As the disturbances seemed to be spreading all through the city, we were approached by our Muslim servants, Jaharbux and Kabat, who came to us with a plea to take the Hindu gardener Mohan and his family into our house for safe keeping. They would be responsible for the Hindus’ care. I didn’t really consider there would be any risk on our part and agreed to do what we could. The arrangements were that we would wait until after dark, and then we would drive down to the old part of the city where Mohan’s family lived and rescue them. Jaharbux would go up into the apartment where they were staying.

We drove to Old Dacca without incident and I waited in the car in the darkness, while Jaharbux disappeared into the building as planned. After what seemed like a long time, he finally appeared with Mohan, his wife and two small children.

At the time, I was driving a station wagon and the family was asked to lie down on the floor in the back. They were covered with blankets and well-hidden, so they could not be seen as we drove through the city. Anyone looking at the car would only see me and Jaharbux. We drove back with the camouflaged family in complete silence, not even a cry from the two children. We could hear distant sounds of rioting all throughout the area but managed to make our way back without being stopped or challenged. Soon we arrived safely back at our house in Dhanmandi, a suburb of Dacca with a sizable foreign contingent.

The house where we lived was surrounded by a wall about six feet high, and the car was kept in a carport. There was a large iron gate in front of the carport’s driveway, the only entrance through the wall’s perimeter. Once inside the compound, we took Mohan’s family to the guest bedroom, where there was also a bathroom. Jaharbux instructed them to remain as quiet as possible and out of sight. At that point, everyone breathed a sigh of relief. The family was with us, and we felt we had not been observed anywhere in the process of bringing them through the city.

The house across the street from us had a veranda on the second floor, and as the evening fell, we joined our neighbors there to survey the situation. I stood there with Susan, looking out to the fires of six villages burning on the horizon, and we heard shouts from the distant crowds. Although we did not feel personally threatened at the moment, we were acutely aware of the danger to others, and there was no guarantee we could not be targets if events turned. We were happy that we had been able to rescue Mohan and his family and retired that night with some sense of accomplishment. When Lyn was tucking Susan into bed that night, she was asked by Susan, who was in sixth grade at the time, if we would be killed. Lyn reassured her that we would be safe, although Susan was not really appeased.

Awaking early the next morning around 7 o’clock, we were greeted by noisy shouts from the area of the big iron gate to our home. Looking out, we saw a crowd of perhaps fifty people, all Muslims. They were demanding that Jaharbux and Kabat, who were standing behind the gate and talking to them, release the Hindu family to the mob. As I watched this from the veranda of our house, Jaharbux and Kabat stood there, facing them. They were adamant that the mob was not going to be let in to get Mohan and his family. Perhaps it helped to assert that the gardener was in the sahib’s house, and under his protection. In any case, they were not going to give in to demands to hand over the Hindus.

This manifestation of sheer guts, empathy for one’s fellow being and unconcern for their own well-being was truly amazing. And, thankfully, the mob dispersed.

We also employed a nightwatchman, or chokidar, who appeared that morning with a cow tethered outside the house, bellowing in pain as it had not been milked. When challenged as to where the cow came from, there was no real explanation but the obvious conclusion was that it had been looted from some Hindu family. Jaharbux and Kabat made him take the cow away. I had never like the chokidar much, and this confirmed my opinion of him. In fact, I suspected in retrospect that he had been the one to tip off the mob that had come for Mohan.

Shortly after this, I learned of other examples of bravery in our area. One of these came from a small Hindu pottery village, not far from our home. The Muslim neighbors of the Hindus in this village had come to the villagers shortly after the rioting was getting underway. They advised them that they, the Muslim neighbors, would not be able to save the village houses or the Hindus themselves from the mob unless they moved to the protection of the police and military who had established refugee protection centers in various parts of the city. If the Hindus took that opportunity, the neighbors might be able to hold off the rioters and maintain their homes and workplaces. After the rioting eventually stopped, I was part of the caravan of people with automobiles who brought these refugees back to their homes in the village. There they were greeted by their neighbors and shown that everything was fully intact. The rioters had come, but the neighbors had dissuaded them from doing any damage, and of course the people had all escaped to safety. In fact, some of the refugee centers where they stayed were homes of government officials who had, with the assistance of the military, set up places of safekeeping for the Hindus.

However, despite these admirable efforts made to protect the Hindus from attacks on themselves and their dwellings, there seemed to be relatively little effort to round up the leaders of the rioting, stop the mobs, or defuse the situation. Within the foreign community, there was an impression of double standards on the part of the government as a whole because of their failure to take strong action from the beginning.

After about three days, we were awakened one night by the unmistakable sound of bagpipes coming down Mirpur Road, the main road leading into Dacca from the western suburbs. It was the army, finally taking some firm action. I felt a surprisingly deep emotional response of hope and relief at the sound. In short order the rioting was quelled. The eerie keening of those bagpipes at night brought to mind Kipling stories about the British army in pre-partition India. By the time the Dacca riots occurred, the hair of the Prophet had already been returned to its rightful owners, whatever misbegotten justifications that existed for the rioting had been discredited, and the violence had degenerated into religious hatred and revenge.

The Hindu family remained hunkered down in our guest bedroom for about four days, and we really saw very little of them during their hideout. Susan had some toys, knew a few words of Bengali, and played with the small children inside the house a bit, using the common language of childhood. Jaharbux and Kabat took care of them as promised, there were no further attempts to storm the house and one morning, once the situation quieted down, Mohan and his family were gone. After they left, Kabat cleaned up the room and announced that there were “bugs” in the room, but he had managed to get rid of them. I don’t know if this was true or not, but a young man who stayed with us later in the year did not complain of any such thing.

Years later, I returned to Dacca and was able to track down some information about Jaharbux and Kabat, but couldn’t find anything about Mohan. I suspect that he and his family ultimately went to India, and hope that whatever happened, they found some measure of safety and peace.

These reminiscences return frequently these days, given the recurrent violent clashes through the world. Although there are many recent examples of violence due to Muslim extremists, they do not reflect the humanity of all Muslims, just as violence from Hindus or Christians cannot be attributed to everyone who identifies with those faiths. I recall with some gratitude the bravery of Jaharbux and Kabat, Muslims whose religious beliefs were as firm and traditional as the rioters, but who protected their friend and faced down a vengeful mob in a magnificent show of courage. Surely it is important not simply to recall the bitter and tragic, but to honor the stories of those throughout the world who are decent and humane, for they too are our history.

You are so lucky to have your father’s story, Khati. Thank you for sharing it here. We such all remember the final sentence: “Surely it is important not simply to recall the bitter and tragic, but to honor the stories of those throughout the world who are decent and humane, for they too are our history.” I will try to keep that in my mind when I feel despair about the world these days.

Thanks, I try to remember those thoughts as well.

Khati, I think I can speak for Retrospect in saying we are so happy that you decided to share this story here. I knew very little about that period of history in Pakistan and now feel the need to learn more. (It also reminds me of Benazir “Pinky” Bhutto, who was a year behind us at Radcliffe.) What a wonderful story about the Muslim staff protecting the Hindu gardener, even at risk to themselves.

I have thought about Pinkie so often over the years. Not that I knew her personally, but having her as a fellow alum a year apart made her career and untimely murder somehow more personal. She was quite a pioneer for women in politics. I think the Bhutto family is still vying for political position.

What an amazing story from your father, Khati. It speaks of bravery and humanity, even in the face of the opposite. i’m delighted you chose to share it with us. And it is also a very good reminder that not all oppressed people look like us or worship like us.

It occurred to me that it was unlikely others would have heard of the events that precipitated the story—and there are so many others we never hear of. For bad and good both. I’m glad my father made an effort to preserve it.

Remarkable story, Khati. Thank you for sharing all of it. As Laurie just said, it IS important to keep your fathers final words in mind and remember that there are good people in the world too.

I don’t know if you read the story I linked to at the bottom of mine – regarding my maternal grandparents’ immigration from “Imperial Russia” (Lithuanian) to Toledo, OH in 1906. They survived the violent pogroms because they were hidden by their Christian landlords. It does happen.

But your story also reminds me of the news today of the clash (again) between Muslims and Jews at the Temple Mount in Jerusalem – holy to both religions, which started with rocks being thrown and is already escalating. Unfortunately, religion is the root of too much hatred.

It is a sad thing that religion seems to spawn intolerance as much as peace and love. I will check out the link you put at the end of your post too. We need stories with hope.

I was thoroughly enthralled by this story, Khati, and am so glad you shared it. There is hope from reading how these brave Muslims protected their Hindu coworker. Personally I have found the Muslims I’ve come into contact with peaceful and delightful people. We in the Bay Area are fortunate to get to know people of many religions from south Asia–Sikhs, Hindus, Jains, Parsis, and Bahais. I’ve been enriched by knowing them and wish others could approach people who are different with openness and curiosity instead of hate and fear.

So glad you enjoyed the story. The Bay Area is indeed a wonderful spot to be able to meet lots of different people. Seems that when you know people personally, stereotypes melt away. We need so much more of that.

A real nail-biter with a lovely ending. Really, the last sentence is artful!

I can see the good parts that are in any faith, but it seems to me that supernatural beliefs have led, on the whole, to more death and hatred than good works and forbearance. This dichotomy led to my very early conversion to atheism.

Amen, ironically. I’m there with you.

Thanx Khati for sharing your father’s intriguing and painful story of the events surrounding that theft of a religious relic in Kashmir.

Am not very savvy about politics or history, but certainly aware that bloody Hindu-Muslim conflicts continue.. I wonder if you’ve seen the film The Viceroy’s House about Lord Mountbatten tasked with effectuating Partition.

Good to hear your family’s altruistic story, but countered alas by too many hateful ones, and now Ukraine.

I haven’t seen The Viceroy’s House, but know that partition was a bloody nightmare. And the story continues, not only in South Asia. Kosovo was another horror but it too is far from unique. It can be hard to hold to the belief in the good in humanity when faced with such coexisting evil, and yet those who choose a better path (at least from my perspective) deserve to be celebrated. The alternative is just too grim.

Yes, celebrate the good, indeed the alternative too grim!