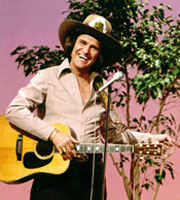

Merle Kilgore, one of the greatest of the story-song writers

When we were young, my brother Leon and I became enamored of “story songs” of a country-ish style. The first song of this type I can remember enjoying was when I was en route somewhere in the backseat of the car, and a song came on the radio. Dad was driving, and he either said something about the song or perhaps signaled his appreciation by singing along to the chorus. Somehow, he made it clear that he liked it—though more typically his taste ran to Sarah Vaughan, Duke Ellington, Frank Sinatra, or the big band sounds of the Glenn Miller Orchestra. The song was “Sixteen Tons,” by Tennessee Ernie Ford. That was a big hit on both the country and pop charts in 1955, so I guess I was five years old. That turned out to be my introduction to a genre I would enjoy for many years.

Trump was the opposite of everything represented by the big man who worked in the mine. I began with an opening verse whose phrasing was very close to the original. Every morning at the Tower, you could see him arrive With soft, small hands, he weighed two-forty-five Wore an extra-long tie, stared at all the girls’ tits And everybody knew you didn't give no lip to Mean Don

A few years later, Leon and I had our own radio in the bedroom we shared. It was on a shelf above his bed, and we had it tuned to a local pop music station. I do remember a few more conventional pop songs we liked, such as Jackie Wilson’s (1959) “Lonely Teardrops” and later, two hits by Gene McDaniels: “100 Pounds of Clay” (1961) and “Chip Chip” (1962)—the latter title referring to “chippin’ at your mansion of love.” But overall, we were most captivated when a song had a story embedded within it. We loved Johnny Horton’s twin hits telling lyrical stories: “Battle of New Orleans” (1959) and “North to Alaska” (1960). Who could ignore a lyric like, “We took a little bacon and we took a little beans,” from the former, or “Where the river is windin,’ big nuggets they’re findin’” from the latter?

Eventually, our favorite would be “Wolverton Mountain,” the story of a backwoods man who kept his daughter isolated and away from all the men who might have designs on her. It wasn’t very subtle. The opening lines were:

They say don’t go on Wolverton Mountain

If you’re looking for a wife

‘Cause Clifton Clowers has a pretty young daughter

He’s mighty handy with a gun and a knife

It was recorded by Claude King, with melody and lyrics credited to King and a fellow with a wonderful name for country songs: Merle Kilgore. I learned in researching this piece that in truth, Kilgore was the composer and lyricist, but agreed to share equal credit with King, since King made a few small adjustments in the lyrics and was willing to put the song on an album he was recording. “Wolverton Mountain” has a great back story too: Clifton Clowers was the actual name of Kilgore’s uncle, and the family lived on a mountain in Arkansas (where Kilgore’s mother grew up) called Woolverton. (Kilgore simplified the spelling for the song.)

Merle Kilgore not only had a good country name but quite an ear for songwriting. He managed Hank Williams, Jr., during much of his career. He was the lyricist and composer for “Ring of Fire,” which Johnny Cash recorded in 1963—and which more people keep on recording, including many mariachi bands—look for them on YouTube! On that work too, for business and professional reasons, he shared the credit—with June Carter (later Cash)—but the song was truly Kilgore’s creation.

I relate all this as prelude to a discussion of one song that was truly special to me from the time I first heard it: Big Bad John, written and recorded by Jimmy Dean and released when I was in seventh grade. That’s Jimmy Dean, who also recorded PT-109, the song celebrating JFK’s heroism during World War II, and was later widely recognized as the owner and featured promoter of a line of sausages. He sold the company to Sara Lee in the 1980s for $80 million and died in 2010.

There were no mines around where we grew up in Indiana, but there was something so iconic about a big man who worked in the mines.

Every mornin’ at the mine you could see him arrive

He stood six-foot-six and weighed two-forty-five

Kinda broad at the shoulder and narrow at the hip

And everybody knew ya didn’t give no lip to big John

He turns out to be a strong, silent type, the kind of quiet stranger who comes into town that nobody really knows, an archetype popularized in the films of actor John Wayne.

Nobody seemed to know where John called home

He just drifted into town and stayed all alone

He didn’t say much, kinda quiet and shy

And if you spoke at all, you just said hi to Big John

Big John turns out to be the savior of the rest of the miners when a safety problem arises, using his great strength and sacrificing his own life in rescuing others.

Then came the day at the bottom of the mine

When a timber cracked and men started cryin’

Miners were prayin’ and hearts beat fast

And everybody thought that they’d breathed their last, ‘cept John

Through the dust and the smoke of this man-made hell

Walked a giant of a man that the miners knew well

Grabbed a saggin’ timber, gave out with a groan

And like a giant oak tree he just stood there alone, big John

Ever since the Internet and especially YouTube came into existence, I have enjoyed going back and listening to this dramatic song. I continued to love the story, and I loved the booming baritone delivery of Jimmy Dean.

In the early months of the pandemic, Randy Rainbow and many lesser-known musicians and song parodists were trying to find ways to articulate through music just how dark a place we found ourselves in, with a President who was perhaps a big man, but was neither heroic, nor empathetic, nor even competent. Trump was the opposite of everything represented by the big man who worked in the mine. I was drawn to the idea of basing my song parody on this very special song. I began with an opening verse whose phrasing was very close to the original.

Every morning at the Tower, you could see him arrive

With soft, small hands, he weighed two-forty-five

Wore an extra-long tie, stared at all the girls’ tits

And everybody knew you didn’t give no lip to Mean Don

As I narrated the more-or-less accurate story of Donald Trump’s life, I kept the cadence and rhyme scheme true to the original.

Accumulating debts that were truly outrageous/He made his real mark on the gossip pages

His business career was taking a dive/But the press loved to photograph his trophy wives, Mean Don

Just as Dean’s lyric took a dramatic turn with, “Then came the day at the bottom of the mine,” my dramatic turn would be the arrival of the pandemic.

Then came the season a virus was spreading

First in Wuhan but then Seattle, and Reading

People were prayin’ and hearts beat fast

Scientists stepped up; data was amassed, for Mean Don

Whenever possible, I looked for ways to pay homage to the original by replicating or just slightly modifying Dean’s phrases. His lyric said, “Miners were prayin’ and hearts beat fast.” Mine said, “People were prayin’ and hearts beat fast.” Dean wrote, “Through the dust and the smoke of this man-made hell/Walked a giant of a man that the miners knew well.” I wrote, “Through the wrecked economy and contagion from hell/Walked this ignorant man as the body counts swelled.”

Dean’s fictional miner dies at the bottom of the pit. I had to think of a different way to lyrically dispense with a living protagonist. “Nobody seemed to know where Donald disappeared/With folk searching frantically for masks and gear/Nurses and doctors were all busy saving lives/They clean lost track of that small-handed guy.”

Dean’s tribute to Big John ends with a marble stand being erected in his memory outside the mine that was never reopened. “These few words are written on that stand/At the bottom of this mine lies a big, big man/Big John.”

In homage to the original, I also end with a few words written on a stand, but it’s not made of marble, and it’s contextualized a bit more suitably, given the person it is recognizing. “Someone made a sculpture, to commemorate it all/Of a gold-plated toilet, near the Viet Nam wall /These few words are written on that stand/Keep on the lookout for an orange-tinted man, Mean Don.”

Once having decided the song was worth recording, I was determined to find someone who could vocally replicate Jimmy Dean. With the help of my brother Hugh, a comedy writer and producer in LA, I was able to find Josh Robert Thompson, a voice actor and impressionist who has worked on late night shows such as Colin Ferguson and Conan O’Brien. He inhabited my lyrics as if he were the ghost of jimmy Dean. Hugh also helped me find a professional vocalist to do the backup singing parts. (She has opted not to be named in the credits, so I am not naming her here.) For the graphics, I hired Shannon Dean, a college undergraduate I had never met, but whose mother had been a student of mine in multiple Education courses.

It’s been over 65 years since I first heard “Sixteen Tons.” And 60 years since “Big Bad John.” I still love both of those songs. And I am so pleased that my very first YouTube creation falls within the tradition of the country/crossover story-song.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Wow Dale, thanx for taking us on your musical journey from Tennessee Ernie to Randy Rainbow to your own Mean Don.

Johnny Cash who you mention in passing is someone whose music I’ve enjoyed over the years. Maybe because I advocate for incarcerated kids, I’m moved to remember his 1968 performance at Folsom Prison.

Great to hear about your advocacy for kids behind bars. I became friends with a guy named Bob Scollard, who was in Folsom for that live concert, and really treasured it as a wonderful memory. One of the few out of his nearly 10 years in Folsom, San Quentin, and Soledad. (When I knew him, he worked as a chef in Boston.)

What a list, Dale! And what a place to start: “Sixteen Tons.” Story songs litter the folk archives, of course (check out “The Long Black Veil”) but the powerful tunes I remember were on Top Forty, such as those you feature above. Story songs nearly always defy the 2:32 rule of commercial tunes, the prescribed length for a hit, so they often survive on the power of their story telling. Don’t forget Marty Robbins’ “El Paso,” and the masterful melodrama of “Teen Angel.” And of course there’s Kenny Rogers and “The Gambler” and… and…

Brief footnote: My partner Susan’s mother used to throw cause parties for the left wing in Manhattan in the 1950s and Susan remembers being forced to sing “Sixteen Tons” for Paul Robeson. Susan can sing, but still…ouch!

I still love that song, El Paso. It was another one that my brother and I latched onto way back when it first came out. Interesting to imagine those “cause parties” in Manhattan,. A far cry from our upbringing in the Hoosier state.

“El Paso” broke my heart! Why did he go back when he had gotten away safely??? And don’t even get me started on “Teen Angel”!

‘A blast form the past’

I really enjoyed your parody “Mean Mad Don,” and of course remember its inspiration “Big Bad John.” While I’m not much of a country music fan, I do remember “16 Tons,” “The Battle of New Orleans,” and “North to Alaska.” Like you, my brothers and I memorized the lyrics and sang them quite a bit.

So glad you included the audio links, and love your parody version of the song. Absolutely brilliant. Story songs are great. Thanks for adding this innovative story to the prompt, Dale.

I agree that these story songs are fun. I vividly remember when “Big Bad John” came out, because my older sister was dating a boy named John, and we imagined the song was about him. Love your Mean Don parody too.

I remember Jimmy Dean (and his song) well, Dale, even before he began shilling sausages. And I can certainly relate to your enjoyment of songs that tell stories. That is part of what I love about folk music.

That being said, your parody of “Big Bad John” is amazing and wonderful! Impressive that you got professionals to record it, wonderfully written, true to the original narrative. Thank you so much for giving us your analysis and the YouTube recording. Funny and clever.

I’m happy with your praise of my song, Betsy. Just to be clear, I paid Josh Robert Thompson (I proposed a fee that he accepted) as well as my graphics editor, Shannon Dean. The backup singer took neither payment nor credit as a favor to my brother. Shannon has continued to help me with production, graphics, sound, and video editing on all of the products I’ve put up on YouTube. The link to my YouTube channel is listed on Retro beside my bio–click on “author’s website” and you get there.

“Mean Don” is hilarious! And I remember all the songs that you mention,.

The very first song I remember hearing on the radio is a story song, Ray Peterson’s “Tell Laura I Love Her” from 1960. One of the strangely popular “Teen Death” songs of that era.

Yes, those teen death songs! “Billie Jo McAllister jumped off the Tallahatchee Bridge.” “Dead Man’s Curve.” etc.

Great song, Dale! You really nailed it. And I certainly remember the original (and Sixteen Tons also). A nice blast from the past with an up-to-the-minute parody worthy of Weird Al. Do you remember Lorne Green from Bonanza? He sang “Ringo” in the same vein as Big John.

Risa, I’ll wear the comparison to Weird Al as gracefully as I can! That’s as high a compliment as any creation of mine couid ever receive. Thanks.