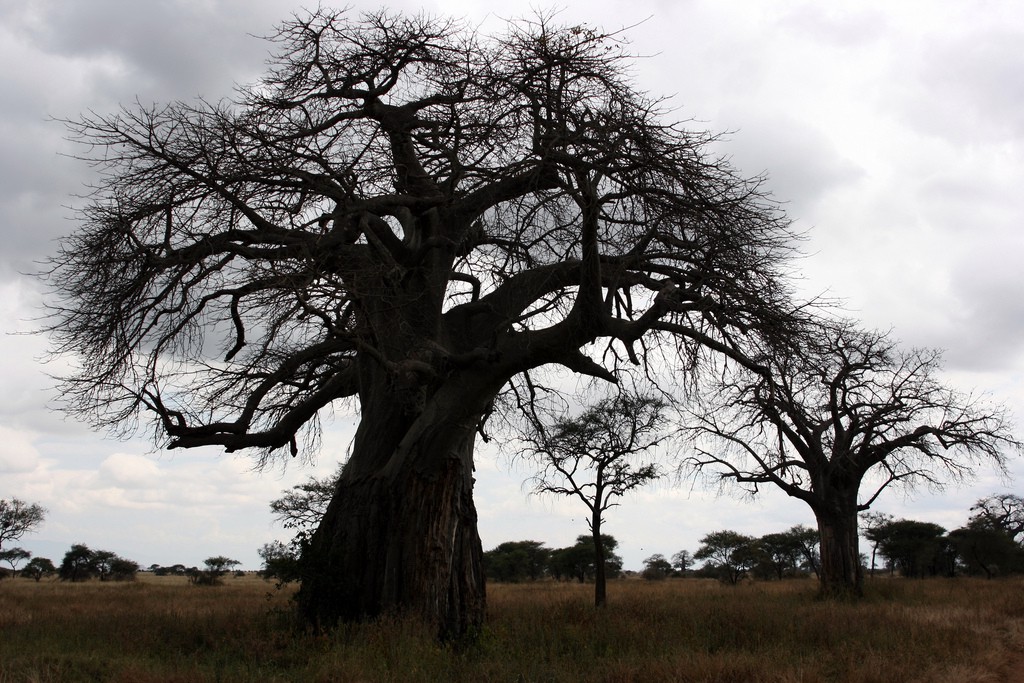

Photo by Abir Anwar via Flickr Creative Commons

These days, one size rarely fits all.

I wrote this for Midcentury Modern Magazine via Medium, January 10, 2018. It’s a different take on genealogy and family trees.

Over winter break, I spent several hours with my eleven-year-old granddaughter being interviewed about the family history on her mother’s side of the family. She also interviewed her aunt on her father’s side. What she learned fascinated her and made her even more curious about her heritage. But then the anvil fell. Her answers on the worksheet were somehow “wrong.”

I love genealogy but am questioning the wisdom of assigning kids to create a traditional family tree. When this same grandchild was in first grade, a teacher gave the class an “all about me” worksheet that began with a line for the child to print her full name. My granddaughter happens to have three middle names. No, she’s not royalty. Rather, she has Jewish and Korean middle names and a belatedly-added name after her Nana died. The teacher told her only one middle name was allowed. Rather than deny a part of her heritage, she wrote only her first and last name and tore up the paper when she brought it home.

When I think about all of my grandkids, I have to question the wisdom of that family tree assignment which most children confront in school. Three of my grandchildren have Jewish-Korean heritage. Because the family tree of one side dates back many centuries but their father was the one who immigrated here with his sister and parents, their answers typically don’t fit neatly on the worksheet. My family tree, which my father used to call a shrub, is a more typical immigration story — but doesn’t go back further than the mid-19th century.

Two of my grandchildren are African American and joined our family through adoption. How will they fill out that worksheet when they are old enough to be given this assignment? Their parents have very limited information about the heritage of their birth families. Will they be satisfied to share the history of their parents’ family trees? What do the great-great grandparents who immigrated here from the shtetls of Europe have to do with who they are?

Then there is the issue of divorce. I have three grandchildren who would be unable to provide much about their birth father’s side of the tree as he is no longer in the picture. My daughter can share a handful of names but no real stories. Can they claim their stepfather’s heritage? What about my other three grandchildren, their step-siblings. How many trees would these children have to create as they also have step-siblings from their mother’s remarriage?

If I were a teacher these days, I would tread very lightly with that family tree assignment. There are all kinds of ways to create families these days, so the conventional concept of two opposite gendered biological parents is often not the reality for many kids. Perhaps a better way to have children share their heritage is to let them tell their own stories in whatever way makes sense to them. Asking an older relative to share an interesting story seems like a reasonable assignment, but maybe not to a child in foster care who has no one to ask. I certainly would never pass out a one-size fits-all worksheet to children and expect their answers to fit neatly into the boxes.

I invite you to read my book Terribly Strange and Wonderfully Real and join my Facebook community.

If I were a teacher these days, I would tread very lightly with that family tree assignment.

Boomer. Educator. Advocate. Eclectic topics: grandkids, special needs, values, aging, loss, & whatever. Author: Terribly Strange and Wonderfully Real.

Important read for all teachers, Laurie. Hoping they get this message somehow.

Thanks, Marcia. For what it was worth, I did let Maya’s teacher know that her assignment was biased.

I was able to get Maya’s religious school principal t admit this wasn’t a great assignment for kids these days. But I also wouldn’t be shocked if they were still doing it.

This is so thoughtful and well said, Laurie. Children’s heritage is more complex than ever, and it is tough to respect all types of families. My niece, who is half Jewish and half Peruvian, interviewed my mother and got a lot of information, but alas, the only living relatives on her mom’s side are in Peru. At least she got to go there as a teenager and meet a couple of her cousins, which was more valuable than any family tree.

Glad your niece had the opportunity to make a connection and meet her Peruvian cousins. As families become more diverse, we need to be more sensitive to children’s feelings about who they are and where they belong. We need to value and embrace diversity, something that our current political climate makes difficult.

Wow, Laurie, you raise such important issues that I never thought about before. Some seem easily remedied – saying that a child can only include one middle name is so absurd that I can’t believe a teacher would stick to that. But others, like the kids who are adopted or in foster care, make this family tree assignment very difficult. I like your idea of letting them tell their story in whatever way makes sense to them.

I’m curious about what response you got, if any, when you published this in Midcentury Modern.

Suzy, I don’t remember getting a much response from Medium/MidCentury Modern, but I did get comments when I posted it on my Facebook page, Still Advocating. Lots of kids from families of all types struggle with this assignment. As I told Marian, making children do traditional family trees is not a good way to celebrate and embrace diversity. After I posted about genealogy and how interesting it was to reconstruct my husband’s missing branch, I thought about this less wonderful aspect of making children do this assignment.