Twenty years ago, the world was shaken by a devastating attack on Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City. I’m not sure how many other artists, authors, and performers created work in the intervening years that responded directly to that calamitous event. One who did was Mordicai Gerstein. He did so in a picture book, The Man Who Walked Between the Towers which was published in 2003 and won the Caldecott Award the following year. In taking a close look at this book, I hope readers of this essay may come to believe, as I do, that children’s books can address even the most painful of subjects meaningfully, can represent and shape our understanding of the human condition, and can at times speak directly to our souls.

The book pretends to be about Philippe Petit. But its hidden subject is about how those who listen are supposed to act in the face of fear. What if there are winds swirling, and what if material objects—even the most massive ones imaginable--turn out to be anything but fixed and permanent?

I believe children’s literature has earned its place alongside novels, plays, painting, film, music, and all the other creative and performing arts. Of course, there are silly and superficial and even bad children’s books, but that can equally be stated about any other art form. Inspiring author/illustrators such as Gerstein deserve to have their names remembered along with Picasso, Margaret Atwood, and Miles Davis.

How does an artist like Gerstein represent the devastating events of September 11, 2001? First of all, he pretends the book is not about that at all. The book focuses on the enthralling story of Philippe Petit, the French wire walker who “walked between the towers” in 1974.

Gerstein foreshadows the destruction of the World Trade Center towers, and the real purpose of his book, when the omniscient narrator states, on an early page, as we are just getting to know the protagonist, that “he looked not at the towers, but at the space between them.” The space between them will prove to be more enduring than the towers themselves, as most adult readers are aware before they open the first page of the book.

After introducing Petit to his audience as a man who is a dreamer and a daredevil–having “danced” previously (and illegally), on a rope he stretched between the two sections of the Notre Dame cathedral in his native Paris–Gerstein then shows us the intensive planning that was required to prepare for Petit’s death-defying feat. He intersperses within his narrative a litany of numerical details: the thickness of the cable on which Petit would walk (seven eighths of an inch), the weight of the reel of cable (440 pounds), the number of stairs his team had to carry the cable to get it from the highest floor of the elevator to the roof (180), the length of the pole he would carry to help him balance as he stepped out from the roof onto the wire (28 feet).

After describing numerous potential setbacks that heighten the drama, Gerstein portrays how Petit finally steps away from the comfort of the roof and onto the wire cable, “Many winds whirled up from the towers, and he swayed with them. He could feel the towers breathing; he was not afraid.” This description, I would argue, is akin to the focus on the “space between the towers,” earlier. It is foreshadowing.

The book pretends to be about the amazing achievement of Philippe Petit. But its hidden subject is about how those who read and listen to this narrative are supposed to act in the face of fear. What do you do in a situation where you stand alone against forces much greater than yourself? What if there are winds swirling, and what if material objects—even the most massive ones imaginable–turn out to be anything but fixed and permanent? In his depiction of Philippe, Gerstein offers us a model of what to do. Philippe “was not afraid.” To the people who watched from the ground, his actions were “terrifying and beautiful.”

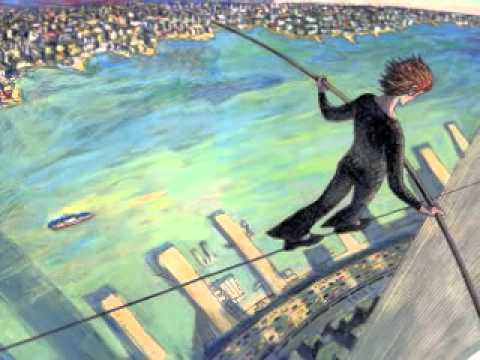

There is much more one could say about the artistry of Gerstein. There are the amazing foldout pages that allow a reader to appreciate the awesome height of the towers as well as the staggering bravery of Petit. There is the way the illustrations are divided into panels of divergent sizes and shapes to direct the eye of the audience. There are creative uses of darkness and light and dramatic contrasts between close-ups (for instance, of Philippe’s foot as he takes that first step from the safety of the rooftop) versus zoomed-out panoramic views of the entire island-city that sprawls below him. One could analyze the subtle (and again, foreshadowing) use of a powerful symbol—an eagle that appears in one illustration near Petit’s wire but is never mentioned in the text. Gerstein even gifts us with a singular moment of comic relief, when the New York City police arrive on the scene. “’You’re under arrest!’ they shouted through bullhorns. Philippe turned and walked the other way. Who would come and get him?”

Let us return our gaze to the ending of the story. “Now the towers are gone.” These simple words in black typeface sit in the center of a blank white page after a series of colorful, active pages filled with both text and Gerstein’s pen and ink and oil paint illustrations. Right after this dramatic page without any visuals, Gerstein gives us a page without any words. He renders the New York City skyline, without the towers, in off whites, muted grays, and hazy greens, yellows, and browns. Next comes the final page: an exact replica of the wordless page before it but with the towers now superimposed as shadowy silhouettes. They are tall and impressive as ever, but we can see right through them to the clouds nestled above the city.

There is no explanation from Gerstein—for the child who might wonder—as to why the towers are gone. Any further elucidation of that reality will depend on the individual interactions between a reader and a listener.

The words on the final page read as follows: “But in memory, as if imprinted on the sky, the towers are still there. And part of that memory is the joyful morning, August 4, 1974, when Philippe Petit walked between them in the air.”

A story about Petit’s wire-walk could have made an exciting story, even if the Twin Towers endured. But no one published such a story. Clearly, the destruction of the towers is the reason we have this book. The wire-walk was dramatic and exhilarating in its own right. But it took on much greater significance after 2001. It was a public act that, one might say retrospectively, hallowed the ground on which the towers stood.

One might also note, in closing this book, that Petit did not actually walk “in the air,” as Gerstein’s final phrase asserts. He walked on that 7/8” wire cable. But he did walk in the space between the towers. That space is still there. And we can all attempt to make meaning out of that, no matter our age or generation, as best we can.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Dale, this is a moving story about The Man Who Walked Between the Towers.

I well remember Phillippe Petit’s feat but altho the images do look familiar and I must have seen them, perhaps in a book review or other feature, I didn’t really know the book before reading your story.

Yes indeed it’s an important contribution to children’s literature, and I love the artwork. Thanx Dale!

Love your final paragraph!

Thank you, Dale, for this introduction to a profound work of art and literature, both for children and adults. And now Notre Dame cathedral is partially destroyed by fire …

Terrifying even in a children’s book, and yes, a perfect way to address the 9/11 events that haunt us. I was unfamiliar with this book , and you deconstruct it masterfully.

Wonderful story, wonderful book…and I’ve just ordered a copy. And yes, as you said, “that space is still there.” Deep and profound, Dale…thank you!! (Have you ever played “Deep But Not Profound?” Wonderful game…I think you’d like it!”)

As with others, I certainly know of Petit (and marveled at his feats) and also about the 2003 book. But that is just both a beautiful and erudite analysis of the book and made me think of it in whole new ways. And, as with Mike, I particularly loved your last paragraph.

Thank you for this amazing book review, Dale, and for the video to help me refresh my memory of this remarkable book. I must confess that, while we read it to children at preschool and I read it to some of my grandkids, it never became the teachable moment it should have been. Perhaps that would have been inappropriate with other people’s children at the preschool, but I regret that I didn’t see it as a way to talk about 9/11 with my grandchildren.

Due to the bug in Retro, I am late to the comments section (I was unable to log on all of yesterday), but let me also add my salute to the bravura choice of a child’s book and your remarkable description of it. Your addition of the YouTube video gives us the full scope of the book and reminded me that I saw the 2008 Academy Award winning documentary “Man on Wire”, which covers the same subject, but for adults and more completely, if not as poetically.

As you rightly point out, children can learn (particularly from sensitive books like this one) how to deal with difficult topics. Thank you so much for offering all of us this guidance as well. And welcome back. We’ve miss you.

After spending yesterday dealing with a possible hack of Retrospect, it was a delight to read your story this morning. What a fascinating book, which could easily be read on a superficial level, but your analysis shows us there is so much more. Like Betsy, I was reminded of the documentary “Man on Wire,” which gave a clear picture of Petit’s history of wirewalking and also the preparation required to make that particular walk. I will definitely have to read this book, even though I have no children any more to share it with.

Petit’s walk was local news for me. I could not believe anyone would, or could, do such a thing. The very idea sort of makes me nervous.