We can only speculate that early humans simultaneously discovered the inclined plane and the wheel worldwide. We know that Archimedes bent the inclined plane around an axis to create the screw. But those technological discoveries apply only to the world of mechanics. Scientific exploration in quantum physics and cosmology, biochemistry, chemistry, computers, genetics, neuroscience demanded technology to capture, measure, and record an ever-widening range of data.

Extropy — an evolving system of tools, methods, and techniques guided by values and standards intended to improve the human condition.

With so many worlds to explore, it’s impossible to survey, digest, or encapsulate technology. And, being lazy, I have no recourse but to explore technology from a personal point of view, through my own interactions with this intriguing, hydra-headed beast.

Family phonograph records carried music into our living room beginning at my birth. Some of my earliest recollection involve listening to music from the Soviet Union (‘The Red Army Chorus’), the Appalachians (Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers), and the Spanish Civil War (‘Viva la Quince Brigada’), all aired through the marvel of audio engineering into our living room. The music was originally recorded on brittle shellac or bakelite disks that spun at seventy-eight revolutions per minute. I was not allowed to play these records; I had broken too many.

From 1955 on, forty fives (seven inch vinyl disks) captured the new music from rhythm to blues to rhythm and blues and rock and roll. Cut into more flexible vinyl disks, these durable treasures were difficult to destroy.

As teenagers, we beat the crap out of them, especially at parties, where they were stacked, scratched, doused in soda and beer, scorched by cigarettes, and tread upon. Vinyl would scar, with every wound amplified on our rackety little record players but we didn’t care. We knew every tune by first chords and by heart.

As teenagers, we beat the crap out of them, especially at parties, where they were stacked, scratched, doused in soda and beer, scorched by cigarettes, and tread upon. Vinyl would scar, with every wound amplified on our rackety little record players but we didn’t care. We knew every tune by first chords and by heart.

On a more elegant plane, my old man built custom high-fidelity amplifiers charged by glowing vacuum tubes and broadcast via specially designed speaker boxes crafted from plywood. We had a remarkable sound system he had designed and my parents would invite the town royalty to after-dinner listening parties to hear live broadcasts of the Boston Symphony.

By the time I was playing Bob Dylan for my parents, my father amplified his sound systems with semiconductors called transistors. They loved Bob Dylan, whose music provided an early common ground to reunite them — however briefly — with their disenfranchised son.

* * *

My first typewriter was a massive Underwood, the kind that I imagined white male journalists and novelists used to pound out news stories, novels, and screenplays, fedoras pushed back off their sweating foreheads, frowning at their arduous literary labors.

I learned how to touch type in high school’s secretary training program. After all, what was a poor girl to do? By the time I was writing college papers and short stories on the old, black behemoth, I had fingers as thick and strong as a weightlifter’s legs.

Today, my fingers lightly tic tic across precise plastic keys, sending binary bursts through an Intel processor and a mother board that translates my tic tics into delicate filigrees of fonts and glowing chromatic graphics. No moving parts necessary!

* * *

The summer following my high school graduation, I took a job in the meteorology department at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. My work? Crunching ancient weather data painstakingly recorded in delicate pen numerals.

The summer following my high school graduation, I took a job in the meteorology department at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. My work? Crunching ancient weather data painstakingly recorded in delicate pen numerals.

My boss was a friend of my old man’s, a pioneering climate-change analyst who wrote the book on long-range meteorology. I would sit in Dr. Willet’s Cambridge laboratory with my pal Steve, converting spidery hand-written numbers collected in dusty volumes by the National Weather Service since 1876 into marks on punch cards.

Wes, the chubby, dirty-haired grad student — a portly, sardonic guy and original hipster — who supervised our tedious work, would collect the punch cards we compiled. Wes would stack and sort the cards into categories (temp, humidity, wind speed and direction) and drop the sorted stacks into slots of a gigantic Cold War-era IBM computer that hunkered on the floor.

Hell, the Cold War was still running hot. A few short months later the United States and the Soviet Union embarked on a chicken match that put the entire world in jeopardy.

When Wes fired up this computer — remember the computer in War Games? — the Whopper sounded like a cross between clattering looms of a textile factory and the roaring, ink-misted press line of a newspaper. The Whopper was loud.

Doctor Willett’s long-term weather database was a big success. It pioneered the process of computer-driven, long-range weather forecasting. It was a big deal.

Today, I could fit the Big Whopper’s entire system, data, and software onto a zip drive the size of my little finger and upload it to my laptop.

* * *

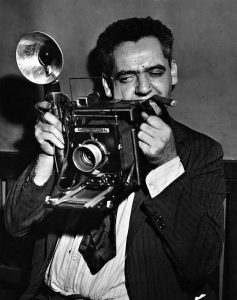

Another early recollection involves learning how to photograph the world with a Speed Graphic bellows camera, crouching under the red safety light of our darkroom. Here, we would project the camera’s negative images through an enlarger and onto photo paper. High on fumes from the developer and hypo fixative, watching images appear ghostly and red onto the surface of the immersed photo paper.

Later, while recalling the experience of developing turning translucent negatives into photographs seemed complex and ponderous. Perhaps that’s why I never carried a camera. I have very few photos from my life in the 1960s and ‘70s. Or perhaps, more simply, I was too engrossed in what I was doing back then to record my experiences.

I’m still not engrossed in freezing moments with photography unless the action includes a collaboration with film makers. I’m just not a selfie guy. Regardless, video’s technological advances I can shoot a movie on my iPhone, and transform the data bits into a feature film with a sophisticated audio/video editing program that fits on my desktop.

* * *

Overall, I love where technology has taken us but, despite technology’s extropic* promise, I find the damn stuff wondrous and dangerous, all at the same time.

*Extropy — an evolving system of tools, methods, and techniques guided by values and standards intended to improve the human condition

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

You take us through quite a compendium of different types of technology that have affected you personally, Charlie. You share each with an engaging discussion. My first job was key punching, so I personally relate to that part of your story. As always, thank you for sharing your thoughts.

Thanks, Betsy. Hydra is probably more a work-in-progress than anything. But I made the deadline!

Quite a journey! I had never thought about the means for listening to music as technology, but of course that’s what it is. And cameras too. You have taken us very knowledgeably through many aspects of technology, not just computers. and cell phones. My favorite image in this story was of you playing Bob Dylan for your parents.

I must admit though, I don’t quite understand your definition of extropy.

I notice that, except for the punch cards, your story focuses on technology to create and reproduce art: music, literature, photography. And while it undoubtedly makes it easier to create art, it also makes it easier for almost anyone to create crap, which we are all now obliged to wade through on Facebook. Fortunately, there’s none of that on Retrospect!

Suzy, I believe the term extropy was coined as the opposite of entropy, the scientific principle that the universe is slowly but inevitably degrading and disorganizing. (That may or may not have been covered in Nat Sci 5.) Extropy is the optimistic notion that human technology can race ahead of itself and solve the very problems that it creates. This does not seem likely in the light of current events, but IMHO the fault lies less in technology than in politics.

Talk about a Hydra-headed monster, JZ! At once, the digital revolution has taken the means of production out of the hands of the bosses and placed them chaotically in the hands of a broad spectrum of ‘artists.’ Yikes!

I didn’t realize that ‘extropy’ had a social component to its definition until I looked up the full definition of the word. I had previously thought it just described the opposite of entropy as you so capably described above. I thing you might be able to add religion mishandled to politics as another damper to the joyful possibility of changing the world for the better. We shall carry on!