Abstract: “Manners” refer to habitual conduct or deportment (see footnote #1). Understanding manners may give insight into human social structures and behaviors. This case study of table manners is based on field observations conducted in the 1960’s in a specific cultural milieu: the United States of America, in the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic states, in a subgroup of families with roots in Northern Europe.

The Goops, they lick their fingers, And the Goops, they lick their knives; They spill their broth on the tablecloth, Oh, they lead disgusting lives!

Methodology: This is a descriptive case study, conducted by direct observation in the “H” family home, primarily between 1958 and 1968. It focuses on table manners in the nuclear family. Comparison observations were conducted in homes of friends and acquaintances of the “H” family, mostly of a similar social subgroup. Validity was confirmed by the Student’s M test (see footnote #2).

Description of Findings:

Early lessons: Children are taught from a young age, when they begin to speak, to learn “please”, “thank you”, and later, “you’re welcome”; these are integral to table manners. To teach this lesson, something may be withheld from the child until s/he says “the magic word” (hint—it is “please”). It is worth noting that these words can and do evolve over time in different contexts; more recent versions include “gimme”, “no prob”, “okay”, “got it”, and even “awesome”, but small children may still be taught the classics.

Family meals: Mealtimes in the observed “nuclear family”—a married man and woman with children–are provided three times daily, usually at a set time (6 pm is typical for dinner). Food is prepared by the mother, who may request assistance from the children or simply indicate, “It’s easier to do it myself!” She also obtains the food from local businesses (“shopping”) with assistance or hindrance from the children.

Roles for Children: Children are always involved in the general meal etiquette of “setting the table”, “clearing the dishes”, and cleaning or “doing” the dishes. The latter may involve washing and/or drying the plates, glasses, utensils, serving platters, and cooking pots, and replacing implements in storage areas. Wiping down dining room and kitchen surfaces, and sweeping the floor are ancillary tasks. Often sparring over social rank occurs over assigned tasks with appeals to parents for adjudication, e.g. “How comes Susie never has to wash the dishes?”, which may be seen as part of the battle for dominance among the young.

Preparation of the table: The table is set with place mats or a cloth, to protect the furniture. Trivets or hot pads are used for containers of food. A fork and napkin lie to the left of each setting, a knife and spoon to the right, and a glass for water above them on the right. Plates are stacked at the head of the table, where the father sits. The family is called to come sit down, signaled by the mother, e.g. “Dinner’s ready”. This is reflected in the familiar adage: “Call me anything you like, just don’t call me late to dinner.”

Customs of food distribution: Once all are seated, prepared food is placed on the table and napkins are placed on the lap, and the father serves the main dish. In some families, I observed a religious ceremony prior to eating (e.g. “good food, good meat, good god, let’s eat!”). Main dish is usually meat of some form, along with portions of side dishes, usually vegetables and some form of starch, and the filled plate is passed to each member of the family. No one is to begin eating until everyone has been served, and all look to the mother for approval ( e.g. “you may start”). If someone would like more food, s/he requests, “could you please pass the …..” for side dishes, and “may I please have some more….” for the main dish, which is distributed by the father, followed by “Thank you” from the receiver, and “You’re welcome” from the giver. Reaching across the table is reprimanded.

Behavior while at the table: Picking up bowls to drink from, spilling food on the table, eating with the hands (there are a few exceptions: corn on the cob, bread), making noise while eating, belching, fighting with siblings, wiping hands on clothing, propping elbows on the table, leaving food uneaten, and talking with a full mouth are all “no-no’s”.

Conversation: Conversation is usually led by the mother, and tends to dwell on topics of the day, progress in school, activities with friends, upcoming plans. Curse words and arguments are not considered appropriate, and interruption is discouraged. Sullen answers may be tolerated as long as some grunting response is provided. Relative silence is preferable to a scene.

The end of the dinner ritual: When everyone has finished eating the main food, dishes are cleared by the children, and a sweet “dessert” is typically offered—ice cream or cookies are popular choices. Following this, the meal is “over”, but children must ask to be excused from the table (e.g. “May I please ask to be excused?”) and not simply run off. Once everyone has left the table, the clean up begins, as described above.

Special considerations: The manners required for more formal events, such as “dinner parties” or “birthday parties”, are decidedly more complex, and are covered in a separate treatise (publishing pending).

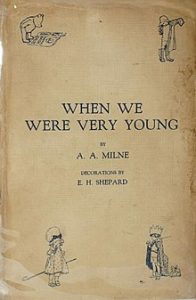

Education methods: Most teaching is provided through direct example and experience. However, for reinforcement, children are also taught with poetry and stories—e.g., “Mabel, Mabel, if you’re able, keep your elbows off the table” (See also “The Goops” by Gelett Burgess—footnote 3, and “Manners” by A.A. Milne—footnote 4).

Conclusions: This case study reflects the complexity of table manners, which may explain why widespread variations have developed. Not every child successfully masters manners, which may cause some social ostracism when in “polite company” later in life. Nonetheless, I am aware that in some homes guests are advised, “In our house, eating with fingers is ALWAYS allowed.” As cultural norms have devolved in the past half century, recent reports indicate that eating takeout pizza directly from the box in a bit of a free-for-all has become quite acceptable. This is clearly a fruitful area for further research.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank my original sources, in particular the “H” family, for their generous time and effort to acquaint me with the intricacies of this subset of mid-twentieth-century American table manners. I give them full credit for any benefit that may come of their efforts, and any lapses in implementing the lessons they provided are entirely my own. .

Footnote #1: Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary, 1977, p700.

Footnote #2: “Student’s M test” measures how well the student doing the research can remember anything anymore these days.

Foot note #3: “The Goops”, Gelett Burgess, c 1900.

The Goops, they lick their fingers,

And the Goops, they lick their knives;

They spill their broth on the tablecloth,

Oh, they lead disgusting lives!

The Goops, they talk while eating,

And loud and fast they chew.

And that is why I’m glad that I

Am not a Goop—are you?

Foot note #4: A. A. Milne, in “When We Were Very Young”, 1924.

If people ask me,

I always tell them:

“Quite well, thank you, I’m very glad to say.”

If people ask me,

I always answer,

“Quite well, thank you, how are you today?”

I always answer,

I always tell them

If they ask me

Politely…

BUT SOMETIMES

I wish

That they wouldn’t.

You had me at “Student’s M test,” Khati, from my scientific study editing days. This is just fantastic and creative. Totally enjoyable! Maybe because I’m not northern European, dinner conversation at our house was somewhat more voluble, but so much of this reflects our generation’s experience.

So glad someone got the reference. Glad you got a chuckle. And yet it’s all true.

Thanx Khati,

I eat my peas with honey

I’ve done it all my life.

They do taste kinda funny,

But it keeps them on the knife.

(I guess I’m a Goop)

Another great table manners ditty!

Oops Khati, I now see I’m not the only Goop quoting that poem today!

Great minds and common experiences think alike!

Great step by step example of table manners and quotes from wonderful sources, Khati. Such fun! And yes, not the only peas and honey reference today. Who knew?

There may have been more homogeneity in our backgrounds than we knew.

Khati, I love the way you wrote this up in perfect imitation of an academic paper, and still gave us real insights into your family’s manners and customs. Very clever and creative! My favorite line: “Sullen answers may be tolerated as long as some grunting response is provided.” Glad to see that you were subjected to the Mabel poem too.

I thought maybe this crowd would appreciate the academic approach. And your familiarity with Mabel strengthens my these that poetry IS used widely to enforce table manners!

Brilliant, Khati!

P.S. We said “Rah rah rub, thanks for the grub, yay God!”

There is food for thought! Maybe a paper on offhand “grace”.

Wonderful, creative approach to the table manner customs with which I grew up in Detroit. I’m afraid my kids had a much watered down version of this, although we did observe the quaint custom of the nightly dinner together. Not so my grandkids. Eating with them feels more like a drive-through than a dinner.

Although this was tongue-in-cheek, there probably is quite a bit to learn about social mores by examining manners. At my brother-in-law’s house in Scottsdale, food is thrown on the kitchen counter and whoever wants to eat grazes by—aaaaah!

Marvelous, Khati. I stopped, transfixed, at the outset, recognizing the Goops. Thank you!

I was surprised to see that poem was published around 1900–so the Goops have persisted in consciousness well over a century now. And I could remember every word—taking up brain space. Sheesh.

Khati, this was brilliant! I am also a fan of the Goops! My kids and a couple of family friends used to play a “good manners/bad manners” game when our families got together. Good manners= pinkies up; bad manners was everything you might imagine.

I love it—my imagination on what bad manners look(looks?)like in your game is giving me a good chuckle this morning. Cheers.

Brava! For finding a new form–the anthropological case study–that I don’t believe.has been previously tried in the thousands of submissions on this site! And you did it so well. The use of secondary sources to buttress and frame the findings of your original data-gathering was a strength. And i especially enjoyed the way you provided examples of the lexicon or usage, you observed, and acknowledged some of the variations. “No prob” indeed!

Glad to be able to expand the horizons of Retrospect submissions :). And glad to have an audience who appreciates it too. Thanks!