Yes, I’m superstitious. I drive on the right side of the road in America out of fear that someone will hit me head on if I stray. I urge Mercury and Venus to keep circling the sun, hoping for reassurance that the next sphere, our planet Earth, will follow suit. I instruct my shaman’s apprentice to maintain a steady beat on a mule skin drum, so I can find my way back from the ether. The drumbeats create a string of beads like Jason’s golden thread, offering the logic of tempo to my entranced brain.

The logic of tempo depends upon two points to establish a rhythm, a line of order that possesses length, direction and purpose. If a heart beats only once, there would be no life. Without the tempo set by two or more beats, there would no logic, no life. Likewise, without tempo, there would be no present. There would only be a now. And then another now. And another. No past. No future. Only now.

The logic of tempo depends upon two points to establish a rhythm, a line of order that possesses length, direction and purpose. If a heart beats only once, there would be no life. Without the tempo set by two or more beats, there would no logic, no life. Likewise, without tempo, there would be no present. There would only be a now. And then another now. And another. No past. No future. Only now.

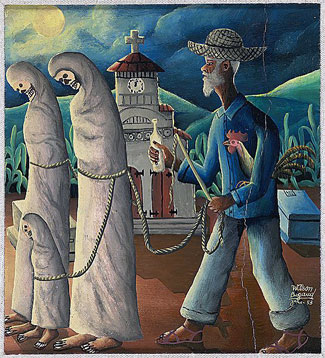

For us to acknowledge time, we have to be superstitious. Superstition asks for blind faith from its supplicants. The shaman who gambles his life and his use-value on his abilities, the zombie who obeys the punishing will of the community, the motorcyclist who leans into the turn, all rely on the unsupportable belief that, in the next moment, what happened before will happen again. Boom, boom, boom, ad infinitum.

Without the next drumbeat, without the continued consensus of condemnation, without the stability of centrifugal motion, without superstition, the entire universe might easily collapse in on itself, sucking the cosmos back with it. So, preposterous as it is, superstition allows us to believe that rhythm marks time, opinion can cause life or death, and motion flies through time and space. Superstition requires intelligence in the form of logic, a grasp of cause and effect, skill sets to drive cosmic events, and the blind faith that if an event happens once, it can — and probably will — happen again. Let’s hear it for superstition.

Without the next drumbeat, without the continued consensus of condemnation, without the stability of centrifugal motion, without superstition, the entire universe might easily collapse in on itself, sucking the cosmos back with it. So, preposterous as it is, superstition allows us to believe that rhythm marks time, opinion can cause life or death, and motion flies through time and space. Superstition requires intelligence in the form of logic, a grasp of cause and effect, skill sets to drive cosmic events, and the blind faith that if an event happens once, it can — and probably will — happen again. Let’s hear it for superstition.

And then, there’s ignorance. Ignorance depends upon denial. For example, I’d have to be in denial to think that the bottle of water on the table next to me was not a collection of crystals and molecules held in temporary suspension by forces described by quantum physics. More personally, if I wasn’t superstitions about the complexities of my body and its workings, I’d have no faith that I would exist in the next moment.

Denial, a root cause of ignorance, usually breeds on a belief that there’s a benefit to denying the existence of a person, place, or event. Denial is also a lazy way out of the need to understand. Ignorance and denial are convenient. For example, in the early 1950s, doctors and medical practitioners tried to introduce the rhythm method of birth control to rural Indian women. In order to help the women track their fertility cycles, each woman was given a device with two-colored beads on a wire. One color stood for a fertile day while another color stood for days in which she might practice sexuality with a lessened chance of conceiving.

Denial, a root cause of ignorance, usually breeds on a belief that there’s a benefit to denying the existence of a person, place, or event. Denial is also a lazy way out of the need to understand. Ignorance and denial are convenient. For example, in the early 1950s, doctors and medical practitioners tried to introduce the rhythm method of birth control to rural Indian women. In order to help the women track their fertility cycles, each woman was given a device with two-colored beads on a wire. One color stood for a fertile day while another color stood for days in which she might practice sexuality with a lessened chance of conceiving.

However, the women, in an effort to please their husbands (and one would hope, themselves, although not bloody likely) would simply slide the required number of beads into the “safe” zone of their device. From that act, they would surmise that it would be “safe” to have sex without fear of pregnancy. Convenient. Ignorance and denial led to the collapse of any faith in the rhythm method, and the birth-control project failed.

In the case of the Indian women, we have empathy. Their ignorance came from deprivation, a lack of education, and a culture that viewed differently cause and effect and the linear nature of time. Their denial was also more innocent. They wished to deny their own physiological rhythms in order to maintain the social stability of the household, or to make it possible (again, one hopes) for them to enjoy sex when they wanted to enjoy sex.

Today, we stagger under the burden of another display of ignorance and convenient denial. We ricochet between theory, superstition, and practice involved in medical science and epidemiology. The circumstances surrounding Covid-19 in America couldn’t contrast more starkly with the opportunistic bead “cheating” of the Indian women. The ignorance and denial involved carry no innocence whatsoever. Still, the effect is the same.

Today, we stagger under the burden of another display of ignorance and convenient denial. We ricochet between theory, superstition, and practice involved in medical science and epidemiology. The circumstances surrounding Covid-19 in America couldn’t contrast more starkly with the opportunistic bead “cheating” of the Indian women. The ignorance and denial involved carry no innocence whatsoever. Still, the effect is the same.

We have a leader, a President thrust upon us, who has no faith, blind or otherwise. He harbors no superstition. He has no wit, no guile, no humor. He has no innocence. He has no motive to understand anything, to do the work of learning. He is too lazy to read; he was too lazy to learn how to read. He grew up, secure in a confidence that he would not need to know anything.

He is psychotic. His sense of reality doesn’t connect with society’s myths, norms, knowledge, skills, superstitions, or theories. In his tawdry imitation of a mad king, he hears only himself and, because he is barren of humor, he is barren of self-assessment and awareness. In parallel with the Indian women and the rhythm method, he has, out of laziness, denial, and opportunism, reversed the passage of time, the polarity of cause and effect, the centrifuge of forward motion. How has he managed this?

In his faux cavalier style, he explained to the American people that testing for the coronavirus created a problem: If there were no tests, we would have no coronavirus. It would disappear, just like the fertile days in the Indian women’s menstrual cycles. In the infuriating way that the media has to soften and normalize, they call this reptilian, limbic twist of logic “magical thinking,” This man, and his reverse logic has no magic. He has no science. He has no tempo, no sequence, no innocence. His ignorance comes from depravity, not deprivation. He has no faith. He has no superstition. Death is the only consort to his twisted logic, and he has brought death to America.

# # #

If an event happens once, it can — and probably will — happen again.

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

You may have lost me a bit Charles, but not your analysis of our national travesty.

VOTE THE BASTARD OUT OR WE’RE DOOMED.

Yeah, Dana, this one took plenty of stretch: science and superstition, blind faith, drumbeats and rhythm methods? What could I have been thinking? I think I was still stunned after having the Village Idiot actually say that if we didn’t have coronavirus testing, we wouldn’t have coronavirus. Wow.

Imbleach him!

Ultraviolet him!

Charlie, as usual, you have given us an amazing interpretation of the prompt! You’ve got me thinking about motorcyclists leaning into a turn in the belief that they won’t fall over, and doctors trying unsuccessfully to get women to track their fertility cycles with colored beads (were these native American women, or women in India?). Your last few paragraphs, describing the menace in the White House, are masterful. I particularly liked, “He grew up, secure in a confidence that he would not need to know anything.” Like so many of your recent contributions, it takes several readings to comprehend all of it, but it’s worth it!

Thanks, Suzy! I apologize for the presumptive logic leaps I made here, but I promise I wasn’t on any inorganic substances when I wrote it. I think Agent Orange blew my fuses with his “magical thinking” on testing. The birth control project took place in rural India.

Another remarkable essay, Chas. I never studied physics (that was my older son’s domain before he expanded out to computational neuroscience), but I suspect physicists might take umbrage to your beginning thesis about the laws of nature being entwined with superstition, yet I take your point and you do “doff your cap” to physics eventually.

I love the steady drum beat throughout, holding the first thought together; truly, we don’t live if we our heart beats only once. It reminds me of a favorite movie scene where the dance instructor teaches his soon-to-be lover to feel the beat by holding his hand on her chest, gently beating the rhythm of her heart.

The rhythm method (beads or no beads) only works if a woman is regular; something I never was. But the Indian experiment you describe is particularly distressing, fraught as it is with ignorance and submissiveness.

Then you explode with the justifiable rage so many of feel at this moment in time. With the ignorant man in the White House, too vain to wear the necessary mask, too ignorant and lazy to bother to read his own briefings, making false claims, filling his head with junk he hears from sycophants on preferred propaganda channels; a complete feedback loop of distain for science, good information, help for our national tragedy. Spouting lies every time he opens his mouth and his cult eats it up and puts us all at risk. You express it well. Death is his constant companion.

Yes, I am happy to admit I was making a biiiig stretch from science to superstition but, once I got myself out there, I was damned if I didn’t push it through. You did pinpoint one of the many “holes” in my screed! Was your favorite movie scene from DIRTY DANCING? The basic rhythm of the heartbeat also drives the mambo, the samba, and — if you throw a backbeat in there — most rock and roll and R&B. I don’t know the various motivations that led to the failure the Indian rhythm-method experiment, so I’m guessing there. And yes, everything this man touches, dies. Perhaps that’s giving him too much power. Everything he touches fails, and reflects the distorted system we live in, wherein constant failure is excused, ignored, and tolerated. Like Jared Kushner and some tentpole film makers we all know.

I confess that DIRTY DANCING is one of those guilty pleasure movies. SHAKESPEARE IN LOVE is my all-time favorite (for many reasons), but I do enjoy the tension, the dancing, the unexpectedness of the pleasure between Baby and Johnny. She grows, he softens and gains self-respect. It is all pat and a fairy tale, but don’t we need to get lost in fairy tales from tine to time? It is a movie I watch and enjoy over and over again. And I go weak in the knees when I hear Solomon Burke sing “Cry to Me”.

“And NOBODY puts baby in a corner!”

Charles, you always make me work for it, but it’s worth it in the end! Thanks as always for a mind-opening, mind-bending, and mind-blowing reading experience. And props for your ability to so eloquently articulate your disdain for our heedless — I almost wrote “headless”; if only — leader; when I try I just end up sputtering and spitting like a blithering idiot.

My apologies for my flights from logic in the first part of “Superstition.” I so appreciate all of you who made the effort to follow me through that little adventure. I felt a little like a technical climber who had taken the wrong route up the cliff face but forged ahead anyway. “Damn the pitons! Full speed ahead.” I don’t know how much longer I can continue to refine my rage and hatred for this man and the community he represents. We shall persevere; we shall prevail! Sounds like Winston Churchill but it’s just me.

I thought that “headless” in lieu of “heedless” represented the kind of slip we should all pay attention to. Good one!

Amazing flow in your story, Charles, and an enlightening take on superstition. I never would have considered our Fearless Leader’s lack of it, just the laziness and no need to know anything. Thank you for a great read.

Thanks for sticking it out through the holes and whimsy of my explorations, Marian! Although I don’t believe the Orange Agent possesses the soul or feelings to subscribe to superstition, he does love conspiracy theories which, in my mind, are simply lazy, simplistic responses to the enormous complexities of social, economic, and political behavior. Thanks for your perseverance!