Martha Lupton Schneidewind was the name of my high school journalism teacher. A tall, birdlike woman, she wore wool suits and ladylike scarves and had a quick, scampering walk. She was kind, loquacious and, to my insensitive teenage self, amusingly absurd with her chirping voice and outdated phraseology.

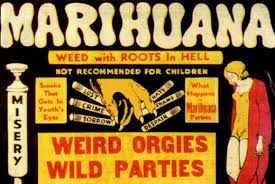

During the mid-1960s, teenage drug use was a huge bugaboo in suburbs like West Covina, Calif. One day Mrs. Schneidewind entered the journalism lab and announced that local policemen had just spoken to the high school faculty about marijuana – a presentation that included the lighting of a joint. If teachers could detect the whiff of weed, the reasoning went, the school could more readily deliver student miscreants to the cops and boost the city’s anti-pot crusade.

“It’s unusually fragrant,” Mrs. S. remarked without a trace of irony when a student asked how the reefer smelled. “Not at all unpleasant.”

Within a few days I was assigned to write an editorial about marijuana for our campus paper, the Spartan Shield. Mrs. Schneidewind didn’t indicate an angle or point of view the editorial should follow, so I figured I had free rein.

Within a few days I was assigned to write an editorial about marijuana for our campus paper, the Spartan Shield. Mrs. Schneidewind didn’t indicate an angle or point of view the editorial should follow, so I figured I had free rein.

I hadn’t smoked weed yet (that wouldn’t happen until the spring of my senior year), but my brother Dan had already been busted for possession and, like most teenagers, I was intrigued by anything that could make masses of grown-ups so freaking scared. There was an immature, forbidden glamour that accrued to drug culture in those days, an excitement that even drug virgins like myself could appreciate from listening to the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” or Grace Slick’s piercing vocal on the song “White Rabbit” (“Ree-ee-member what the door mouse said! Feed your head!!!”).

To write the editorial, I referenced a booklet I’d bought at the Free Press Bookstore, a hipster haven in the Fairfax district of Los Angeles. The booklet had a glossary of terms about marijuana (“bomber” was a big fat joint, “pinner” a thin joint), and I naively incorporated those terms in my piece to simulate a streetwise, insider’s perspective.

It didn’t occur to me at the time, and I have no proof, but I suspect my marijuana assignment originated with the West Covina Police Department. I say this because when I finished the editorial and submitted it to Mrs. Schneidewind, she sent it to the assistant principal Barbara Buch for approval. Miss Buch, I now believe, was deputized by the West Covina P.D. to contrive the Spartan Shield editorial.

Miss Buch (rhymes with “spook”) was an odd lady. Although it was her job to enforce the dress code for girls – skirts had to be no more than an inch above the knee – her own sartorial style would have to be described as Aging Stripper. She wore a cake of makeup, shaped her eyebrows like arched caterpillars, and favored sexy blouses and wide patent-leather belts that emphasized her generous bosom. According to a persistent campus rumor — total myth, easily dispelled — Miss Buch was a former Playboy centerfold.

I never spoke with Miss Buch, but a day or two after submitting my marijuana editorial I was taken aside by Mrs. Schneidewind. From her desk drawer, she pulled out my typewritten copy and showed me the additions Miss Buch had made to my editorial – additions that totally altered what I’d written.

Among her gems was this unforgettable line: “The casual marijuana user may embark on his drug experiment innocently enough, only to emerge from his ‘high’ with needle marks in his arm.”

I’d never smoked pot or tried drugs of any kind, but I recognized this as anti-drug hysteria. “That sentence needs to come out!” I said. “I didn’t write that and it’s not true.”

“I’m sorry,” Mrs. Schneidewind replied. “But this is final. The editorial will run this way.” Worse yet, it ran that way with my byline attached.

Looking back, I imagine Mrs. Schneidewind felt trapped — that if she had resisted Miss Buch’s edict and defended my journalistic honor she’d be risking her job. I never knew Mrs. Schneidewind to be unethical or heavy-handed on any other occasion – in fact, we remained friends and stayed in touch until she died in 2000 — so I feel certain that was the case. But my sense of betrayal at the time was sharp and painful.

Looking back, I imagine Mrs. Schneidewind felt trapped — that if she had resisted Miss Buch’s edict and defended my journalistic honor she’d be risking her job. I never knew Mrs. Schneidewind to be unethical or heavy-handed on any other occasion – in fact, we remained friends and stayed in touch until she died in 2000 — so I feel certain that was the case. But my sense of betrayal at the time was sharp and painful.

A few months later, I smoked my first joint with Flip Farrall, another member of the Spartan Shield staff. Most weed came from Mexico back then, and when you bought an ounce (“a lid”) it was mostly seeds and stems. Terribly weak. I remember taking long draws on the stuff, trying my best to get a buzz. It took a while to get the hang of it. And no, fergawdsakes, I never woke up with needle marks in my arms.

Today, I still occasionally get high and also use cannabinoid-based medicine for sleep and pain. I feel grateful that marijuana prohibition finally came to an end in California in 2016. I only wish Fraulein Buch had lived to see the day.

I love the way this young journalist reacted to the badly edited version of his work, while at the same time understanding the difficult position of his beloved teacher. This really captured the time period, when reefer madness was a common hyped-up reaction to kids who were just beginning to experiment with smoking those “seeds and stems.”

What a great story… Evocatively written. We didn’t have too much reefer madness in the late 60s /70s here in the Bay Area… we had drug education. They stopped that at my high school when they realized that they were telling us how to do drugs and we figured out that drugs wouldn’t kill us done properly 😉

Thank you!

I’m impressed by the empathy you show for your teacher—perhaps more than she deserves. She was, after all, negating the core principles of journalistic integrity by not only altering what you wrote but also insisting it be published under your byline. I’m glad this incident didn’t dissuade you from actually becoming a journalist! Perhaps it even gave you extra motivation. Great story.

Just discovered this terrific story after reading yours of this week about 1968. Love the way you incorporated “hip” terms you had read so you would sound streetwise. I was expecting it to lead to you being busted. But having your editorial rewritten was almost as bad. Did you get any feedback from your schoolmates about that “needle marks” sentence? At my school, we would have ragged the author mercilessly! Looking forward to more of your stories.

Terrific story, which I particularly appreciated as a fellow high school newspaper editor. (Coincidentall,y our high school nickname was also the Spartans, though that was not part of the newspaper’s name.)

I never had to deal with such censorship, but my editorials were pretty tame (computerized dances; old furniture that snagged stockings, etc.); plus, at this place and point (Connecticut in the mid-60’s), drugs had yet to work their way down to high school level. But I sure felt your pain and you describe the situation beautifully and with notable restraint. I found the mandated “needle marks” addition particularly aggrevating; that “gateway” argument has been trotted out for years and years and there is still no evidence of it.

Thanks, John!

It must have been so painful, especially at your age in the story, to have been edited and have someone else’s words attributed to you. There was ridiculous drug hysteria back then. These days, opioids are a far greater danger than pot.

Those were the early days when pot was working its way into high schools. It sounds very familiar. I sometimes felt sorry for the kids who followed and really did have issues with being stoned all the time. I was also half expecting that your efforts to incorporate streetwise terms would end up with a visit from the West Covina police—but you just got a lesson in censorship instead. None of which impeded further experimentation of course. Great story.

Thanks, Khati!

Great story of your infamous pot editorial Edward!

And once you got the hang of it, I’m so glad you woke without those tell-tale needle marks!

Thanks, Dana!

That’s one terrific story. It must have been difficult for a kid to learn about the complexities of life by being betrayed by a school administrator, Miss Buch, you should have been able to trust. You’re almost certainly right that Mrs. Schneidewind, despite being the one to bring you the bad news, was caught in the middle. It’s heartening to know that you and she remained friends for life. One thing I noticed, though. And that is that you didn’t say anything about how the other students reacted to you once the piece was published. I imagine some of them give you a hard time, while others simply took it in stride, saying, in effect, Well, that’s teachers for you.

Hi Fred, thanks for the kind words. You mention that I didn’t comment on the reactions of other students. You know, I really don’t remember any reactions, pro or con, from fellow students or the other kids on the newspaper staff. That was more than 50 years ago. Such is memory: Certain aspects of the story seem crystal-clear, others quite fuzzy.

Loved reading this again! The fraulein crack made me laugh. We will have to exchange our school paper stories sometime.

Thanks, Risa!

A fun story. By the time I hit high school in 1974, no one seemed to really care much about pot other than the problem of having a record if you were caught with it.

It also reminded me of this lament about lost love and bad weed:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GNWw2NFo_ec