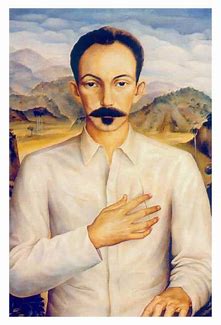

Jose Marti, Cuban poet and revolutionary

In Havana, school children line up for everything. They sit in a line on the ancient curbs of Habana Vieja, knees protruding from the skirts and shorts of their uniforms, waiting for their turn at the cafeteria. Like children everywhere, they stand in line at bus stops, on field trips, and at ice cream stands.

“Que lastima,” says a delicate-featured little girl. What a pity.

At the birthplace of Jose Marti, Cuban poet, essayist, journalist, professor, and revolutionary, they tip-toe one after another from room to pristine room, hands clasped behind their backs, peering into the glass cases of papers, pens, and books that capture the history of their national hero.

At the birthplace of Jose Marti, Cuban poet, essayist, journalist, professor, and revolutionary, they tip-toe one after another from room to pristine room, hands clasped behind their backs, peering into the glass cases of papers, pens, and books that capture the history of their national hero.

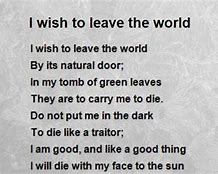

Marti was as much a poet as a politician. In Cuba, as in much of South and Central America, poetry, like music, plays a pivotal role in the spirit and politics of the people.

Every day, on my way to the conference at the writers union, I take pictures of cars, dogs, people of different colors. The walk through Havana’s Vedado district takes me past rows of dilapidated mansions that once housed wealthy families.

Now the buildings are falling down. People care for them, but paint is scarce in Cuba, and repairs to scabbed and peeling window frames and doorways are nearly impossible. Most mansions house governmental offices, including UNEAC, the national writers union, where I attend the conference.

On the way back to my hotel from a meeting at the union, I come across two boys playing in the street. One child is pale white, of Spanish descent; his friend is coal black. Their mannerisms are identical: two kids goofing.

“Hello!” I shout and grin, pointing to the frozen duo. “A photo…it’s okay?”

“No, no,” they say.

I laugh and continue to focus the camera, thinking they are kidding.

“No, no,” they repeat. One of them wags a finger at me. I see through the viewfinder that they are serious. I put down the camera and shrug.

“Okay, guys” I say and begin to walk away. I turn and apologize. I am sorry. I just played the ugly American thing perfectly.

A few days later, I spot the two boys fidgeting with a larger group of kids in the yard of another grand but crumbling Vedado-district edifice. Behind a wrought-iron fence, a circle of children clad in school uniforms sits beneath a portico that once must have received the carriages of elegant callers.

A few days later, I spot the two boys fidgeting with a larger group of kids in the yard of another grand but crumbling Vedado-district edifice. Behind a wrought-iron fence, a circle of children clad in school uniforms sits beneath a portico that once must have received the carriages of elegant callers.

The children have gathered around the teacher who sits on the edge of the steps, reading aloud from a book. The gate is open and I slip inside, taking the camera from my bag. I dash up the broad stairway and lean against a marble column, framing the circle of students in my viewfinder. The picture is perfect. The children are stretched out below me, others are playing the background, and the teacher has her back turned. She has not noticed me.

I make sure the flash is off so not to disturb their work. A heavy hand falls on my shoulder, jarring the camera out of focus. I turn to encounter an angry woman. “Leave,” she whispers in Spanish. “Get out. Immediately.” She shakes her head; an incriminating frown tightens her forehead.

Muttering apologies, I ditch my camera and stumble down the stairs. The teacher who has been reading to the circle of children turns to glare up at me, the white intruder stealing forbidden images. The children look vulnerable, knees and elbows protruding from shorts, skirts, and pinafores.

“With your permission,” I say. “I am sorry. It was an insensitive act.”

The woman does not soften. I should know the law, her expression says. I back down the broad marble staircase, pocketing my camera. The children stare as I slink down the stairway and onto the street.

The angry woman closes the gate behind me and drops the latch firmly into place. Two other women peer down at me from the broad double doorway between the marble columns. I slither away, my shoulders sagging with shame. From now on, I will take my photos unobtrusively or not at all.

What could I have been thinking? I walk the tree-lined streets toward the writers union. Would the staff of an American school let a stranger on the grounds to snap photos of the students? I don’t think so. Should I be surprised at their reaction here in Havana? Before I round the corner, I turn back for a last look at the school.

A second line of children wiggles like a disjointed centipede in front of another teacher. The children are all smiling and dancing in place. My camera stays in its bag.

A week later, the conference is over. It is also the day before Jose Marti’s birthday. I am walking to the writers union to say goodbye to my Cuban colleagues and deliver two reams of paper and packs of Bic pens. Resources like this are valuable in Cuba; there is never enough to go around—of anything.

As I approach the school I hear the sound of a bass drum and cymbals beating out an irregular tempo. I round the corner and there, in the schoolyard, a double line of children are marching. At the rear of the line, a diminutive student struggles with the great round of a bass drum and a little girl holds her head away from the cymbals she is crashing together. The students are executing dance steps to the simple boom-boom-crash of their rhythm section. I stop at the gate.

In my bag, along with my camera, I am carrying the reams of paper and enough Bic pens to supply every child in the school with a writing instrument. The writers union has paper. But how about this school? Do they need supplies? I can only assume that they do: Why not make up for my ugly American karma and hand over the goods?

I signal a teacher from outside the gate.

“Excuse me, señora,” I call out gingerly. “I have paper and pens here.” I wave the hefty ream of paper over my head as if I were a child in class with the correct answer. “For your students,” I add.

The woman stares through the gate at the ream of paper, the words written in English on the wrapper, “Xerox MultiUse.” Corporate America is on display. I hold the Bic pen packets in my other hand. Now I feel like a trader holding up glass beads and tin utensils. My shame is boundless. She looks at me, at the paper, at the pens, and smiles carefully.

“Esperarse.” she says. “Wait here.” She turns and treads lightly up the steps to disappear into the dingy darkness behind the stained, cracked, and unpainted front doors of the mansion. She returns immediately with the woman who had kicked me off the school grounds a week earlier.

“La directora,” the teacher says. The directora does not recognize me, but she looks at the paper, the pens, and then looks straight into my face. I see recognition flash across her features. “Ah,” she says. “You. The American.”

“I’m a writer, one of 20 visiting from the United States. We are attending a conference, at UNEAC.”

“I’m a writer, one of 20 visiting from the United States. We are attending a conference, at UNEAC.”

She nods and her face softens a bit. She knows UNEAC. It is a prestigious union in another crumbling mansion right down the street.

The director takes the package of paper and the box of pens. She smiles hesitantly, then looks away.

I nod and turn to go.

“Excuse me,” she calls out in careful English. “Do you wish to visit our school?” Her penciled eyebrows raise with the question.

“I would love to.” I feel relieved and excited. It has been difficult to make everyday contact with the Cuban people. The conference has kept us busy and at night, I frequently find myself in bars and restaurants, carousing with my writer colleagues. But writers invariably form colonies when they gather, whether American or Cuban or French or Nigerian. I have met few “folks.” My escapade blew my first attempt to get out and around. Now I am being given a second chance.

“Wait here. I will bring the professor of English.”

The English teacher comes out of the doorway. She is small and dark, what the Cubans call mulatto, with large brown eyes. She is wearing a green-and-black striped sweater and a long skirt. She takes my arm and leads me down the steps, across the pounded dirt of the schoolyard on a slate walkway. We round the corner of the main building and turn down a driveway toward a smaller building that must have served as a carriage house for the mansion. The stables have been converted into a classroom.

Inside, my eyes adjust to the dim light.

Small children are seated in rows at tiny 1920s-vintage desks. The desktops have holes for inkwells. On the desks, in front of each child, is a three-inch square of paper. The teacher is a tall, black woman. In rapid-fire Cuban Spanish, she explains who I am.

The children all turn around and stare. The teacher asks them to greet me. They do, in a solemn chorus. The teacher explains to me that the students are writing poems to José Marti on the tiny squares of paper. They are five years old.

I calculate how many sheets of my Xerox paper would be required to give these students the materials they need to complete another writing assignment: about four pieces. The teacher asks the children who José Marti was.

“La patria de Cuba,” a child answers, then volunteers, for my benefit, “he lived in America.” They are five years old and writing poems about José Marti in the dim light of the old carriage house.

We say goodbye to the tiny students and step out into the gray light of day. The English teacher puts a hand on my forearm and leads me back around the corner to the front door. Her hand is soft and warm, comforting.

“Let’s meet some of the older children,” she says. Inside the mansion’s scarred, massive double doors, the darkness of a high-ceilinged foyer is pierced by a shaft of warm light. The light is coming through a stained glass window that bears a European-style coat of arms. The window dominates a broad marble staircase that splits into two courses and curves up and around to a mezzanine decorated with carved stone balustrades.

“This must have been a grand residence,” I say.

“It was a single family dwelling,” she says.

“Before the revolution.”

“Yes, before the revolution,” she replies. “This was a wealthy neighborhood, but all the people left. This home has been a school since that time.” We climb the broad front stairs that I had leapt upon to photograph the children a week earlier.

Upstairs, on the mezzanine that surrounds the large foyer below, a display has been set up. Small, hand-drawn portraits of José Marti are accompanied by verses written in childish handwriting. “Poems written by some of the older children,” she explains. “And here is a computer.”

The computer is not a computer. It is a sculpture made of styrofoam. It has been carved with a bread knife. I can see the striations that the serrated knife has cut into the white bubble material. A picture of a Microsoft Word document has been pasted on the screen and a representation of each letter and symbol on a standard computer keyboard has been pasted onto the hand-carved keys.

“For the students to practice,” she says.

I think of my powerful, portable laptop, sitting in my hotel room like an idle jet plane. We knock on the splintered panel of a classroom door.

Two girls in the white blouses and red scarves of students open the door. There, crammed between a blackboard and the first desk, a child is working through a row of arithmetic problems. The high-ceilinged room has ornate moldings on the walls and ceilings and is small; its tall windows are shuttered but open out toward the back of the mansion. It was probably a bedroom. The teacher stands in the back of the room. I wonder how she got there. There is not enough space to walk from the front of the room to the back between the desks.

The English teacher holds my arm up. “This man is from the United States,” she says in Spanish. “He has come to visit us. Would you like to say hello?”

These children look at me with big eyes. They are older. I apologize to the teacher for interrupting her class. She simply smiles at me and turns to the class. “Preguntas?” she asks. “Any questions?”

Slowly, one child, a thin brown-skinned boy, raises his hand. The teacher recognizes him.

“What kind of writing do you do?” the child asks.

“I write songs and plays and novels and movies and I write schoolbooks for children.” This answer makes them smile. They look at each other and giggle.

“What do you think about when you write schoolbooks?” another child asks. Now it’s my turn to grin.

“I try to remember what it is like to be bored in school.”

Laughter. The teacher approves.

“Do you like our writers?” a third child asks.

“I only know a few of your writers. Many are not translated into English. Right now, though, I am reading Jose Marti.”

The kids grin and exchange glances.

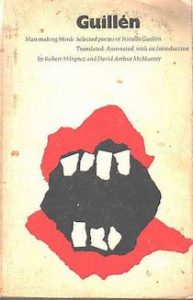

“Do you know Nicholas Guillén?” Another student asks.

“Do you know Nicholas Guillén?” Another student asks.

“No,” I answer.

The children look at me as if I were from another planet.

“Tell me about him.”

“You should read Nicholas Guillen,” a little girl says. “He writes beautiful love poems and stories.”

I take out my notepad and write the name down. “Now the grownup is learning from the students,” I say. The English teacher translates and the students laugh.

We move from room to room. Each class rises to greet me; there is no pushing or shouting. We talk about what I think about Cuba. They ask me if it is true that children in America bring guns to school.

“In some schools, yes.” I explain that in most schools in America, there is no violence, but that in some places, violence is a problem.

“Because the people are poor,” a child adds.

I look around at the splintered shutters of the crowded classroom, the paint peeling off the walls, the ancient chalkboard. “Yes,” I reply. “Because in America, many people are well-off and happy but in other places in America the children and all the people are poor.”

“Que lastima,” says a delicate-featured little girl. What a pity.

# # #

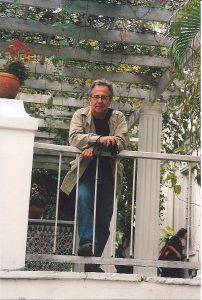

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

What a powerful story. My husband and I were in Cuba in January 2017 with Road Scholars. So much of what you describe is right on target with what we saw and learned. I’m struck by the knowledge of poetry and the curiosity of these Cuban students. They are likely living in poverty with few of the things even poor American children take for granted. We wondered about this when meeting with a college student who knew more about world politics than most American college students. He had access to a computer at school for a very limited amount of time. Thanks for sharing your story.

I’m glad you enjoyed it, Laurie. I’ve been to Cuba twice with a significant time span in between. The first time, my partner Susan Rubin (a playwright) took a show to an international festival in Santiago de Cuba, during what was known as the Periodo Especial , a time of drastic austerity, caused by the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba’s foremost trading partner and aid resource. People were starving, but they continued. We played music everywhere, and the kids at the music school nearby had a deep knowledge of American jazz. They could jam, man!

This writers conference was held in Havana in 2000 and you got precisely what I wished to convey, i.e., (dangerous generalization to follow) Cuban kids are very secure regarding their values and lifestyle. Poverty is basically not an issue. That changed during the Obama presidency, when Cuban Americans were allowed to send money back to their families. Then a kind of apartheid set in: most of the people who left Cuba after the revolution had Spanish blood, they were the pre-Revolutionary upper classes. The blacks had no place to go. They stayed and built the revolution. Few of them have families to subsidize their life-style now. So, a gap is growing, probably exacerbated by the rise in tourism. Ain’t life grand.

A wonderful story about a culture most of will never glimpse. How telling that you were strictly forbidden to photograph these children randomly, but you were welcomed when you came bearing useful gifts, showed respect and identified yourself as a writer, having just been at a well-know conference.

Your engagement with the children is delightful and interesting as well, Charles. You are a true educator, who can interact with all ages, listen, learn and inform. Particularly your own readers. Thank you for this.

Thanks, Betsy! The relationship with those kids was as memorable or more so, than the entire conference. Well, no, maybe not…

This is a magnificent story! I know a lot about Martí as a revolutionary, but didn’t realize he was a poet too. Now I need to look for his poetry. And I have always wanted to visit Cuba, since the days of the Venceremos Brigades. Thanks to your story, when I finally do go, I will be sure to bring paper and pens for the schoolchildren so that they will talk to me. Love the picture of you at the railing too – is that the UNEAC mansion?

Poetry, like music, completely imbues Cuban life, country and city. And society integrates poetry there (or used to) into its politics, conversation, everyday life.

That picture was taken at Hemingway’s finca (farm/ranch) outside of Havana.

This was a truly immersive read that painted a very credible “vraisemblance,” at least for someone who has long wished to visit Cuba but never has. The use of dialogue with both adults and children was an especially strong feature of the writing. Thanks for this wonderful reminiscence.

Thanks, Dale. Cuba was going through a very difficult time, but life never skipped a beat!