This year for the first night of Passover I attended a Seder at the home of my friends Neal and Chris. A soulful, beautiful evening. Thirteen of us sat at a table decorated with floral arrangements, crystal wine decanters and silver candlesticks.

"Although my father was Jewish, our family never celebrated Passover or Chanukah, never had a menorah in the house, never attended a Seder. As a child I never felt deprived of the things my non-observant father never taught me about being Jewish. But I do now."

There were the bitter herbs and charoset, the matzah crackers and celery dipped in saltwater, a delicious brisket. We took turns reading out loud from the Haggadah, told stories and briefly reflected on the frightening state of the world and the role of faith in assuaging one’s fears.

We sang, someone drummed, and at one point each of the men and women at the table named something for which we were grateful.

This was only the fourth or fifth Seder I’ve attended. Although my father was Jewish, our family never celebrated Passover or Chanukah, never had a menorah in the house, never attended a Seder. As a child, I didn’t feel deprived of all the things my non-observant father never taught me about being Jewish — but I do now. I think I missed a lot.

I am the son of a mixed marriage. My mother was a Presbyterian missionary’s daughter and when she and my father married they decided to let their children choose their religion. “It’s up to you,” they always told us. But given that my dad rarely talked about being Jewish, and only went to temple when our grandmother visited from Chicago, my brothers and I didn’t really have a knowledge base from which to make a choice.

My mother on the other hand was a regular churchgoer, and since I was much closer to her than I was to my moody, autocratic father, I gravitated by default toward her religion. Two or three Sundays a month I’d slick down my hair, wear my slacks and dress shirt and black leather shoes, and go to Sunday School while my mother listened to Pastor Kent’s sermon in the chapel.

In retrospect I wonder if, by taking my brothers and me to Sunday School, my mother was also giving my father a brief respite. He worked six days a week, and often used part of his Sunday to do the bookkeeping for his Western Auto store. That little window of time when all of us were out of the house, probably the only silence and privacy he experienced all week, must have been a treasure to him.

Unlike my brothers Dan and Dave, I started taking religion seriously. At 13 I was Baptized and became a member of the Presbyterian church. I liked some of the kids in the communicants class that was required to join the church, and I attended Youth Fellowship each Friday night. I was a lonely kid struggling to find comfort in myself, so the church — its litany and prayers, its music, its veneer of stability and moral rectitude — appealed to me. It gave me something to belong to.

My dad never taught me the first thing about being a Jew, but that oversight wasn’t a simple act of negligence. He just didn’t have the tools: neither the warmth and ease that a boy craves from his father, nor a deep familiarity with his own religion, nor a gift for communication. Although his mother was an observant Jew, he told me much later, “my father had no religion at all.”

For Jews of my father’s and grandfather’s generations, especially working-class Jews, that was a common scenario. Anti-Semitism was abundant and often virulent in the early Twentieth Century, and American Jews had to struggle much harder to succeed. By downplaying one’s Jewishness, they felt they could blend in and give their families a better life.

The price of overassimilation is a sad aspect of any immigrant story. I remember meeting Steven Spielberg in 1993, when I interviewed him about his movie Schindler’s List for the San Francisco Chronicle. Spielberg told me that film changed his life, gave him a sense of Jewish pride he’d lacked while growing up in Arizona.

“My Jewishness was a shanda for me,” Spielberg said, using the Yiddish word for shame or embarrassment, “because I was brought up in a Gentile neighborhood in Scottsdale, Arizona. I just felt like I was on the outside, that I wasn’t part of anything — and I blamed a lot of it on my Jewishness and my Semitic look.”

He said he hated going to Hebrew School in Scottsdale, that he was bored and restless and only went out of obligation – “in the service of pleasing my parents.” But when his wife Kate Capshaw converted to Judaism in 1991, Spielberg went through the 12-month conversion process with her. “I learned more in one year with her than I had learned all through my formal Jewish training.”

Soon thereafter he directed Schindler’s List, the story of a German industrialist who saved the lives of 1,200 Jews during the Holocaust. Making the film was emotionally depleting and difficult, but a profoundly life-changing experience. “I’ve never identified more as a Jew as I have in the process of researching and producing and directing this film,” he said. “I mean, the best thing that probably could happen to me is that I’ve reconnected as a Jew. No one can ever take that away from me.”

Spielberg’s story inspired me and to this day when I’m asked to name my favorite celebrity interview, I often mention Spielberg and Schindler’s List. His story didn’t compel me to dive deep into Judaism, however, or to return to the Christian practice I’d drifted from after high school. I’d love to feel the comfort a lot of people derive from being part of a faith community, but I’ve grown suspicious of religious structures and their frequent inclination toward division and judgment.

Being the product of a Jewish father and Protestant mother, I still feel some connection, more cultural than religious, to both traditions. I could never deny the presence of either in my life and in my personality, any more than I could deny my genetic structure. But if I had to define myself spiritually today, I’d say I’m a universalist agnostic.

Last night at the Seder when Neal asked us each to name what we’re grateful for I mentioned friendships, dogs and nature. That’s where my reverence resides: In the dazzling canopy of stars you see in a remote country sky; in the ego-less welcome of a Labrador Retriever’s eyes; in that double rainbow I saw while driving into Marfa, Texas following a summer squall.

Thank you for sharing this graceful story. I too was an awkward teenager who found my first identity and acceptance at Sunday School—though for me it was my Jewish temple youth group rather than your Presbyterian fellowship group. And I too found my way to a similar place. Friendship, dogs, and nature sound like Truth to me.

Edward, this story thoughtfully describes your perspective on your parents and your connection to their different religious backgrounds. I’m grateful for whatever brought you to that lovely Seder table this year because it inspired this look back to a time of life when you were struggling to find comfort and a sense of belonging. I loved reading about the Spielberg interview and the reason this became one of your favorites. Gratitude for friends, dogs and nature–excellent choices.

Edward, I found your story profoundly moving. As I said in my story, we were VERY Reform Jews, not very observant, until my brother decided at age 12, that he wanted to be bar mitzvahed. Then we started lighting the candles and saying the blessing on Shabbat. We always went to fun Seders, belonged to temple (the same one as John, actually), and I attended Sunday School and learned about my religion, sang in the children’s choir. But it was my brother’s quest that sent the whole family to weekly services. My brother is now a well-known rabbi and professor at Hebrew Union College. But I married a man who, though of Jewish birth, wasn’t raised with any traditions or learning in the household and I think that has caused a big gap between us. Finding gratitude in nature, friendship and dogs is lovely. I endorse your choices whole-heartedly.

Thanks, Betsy. What is your rabbi brother’s name?

Richard Sarason, long-time professor at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, and frequently published author; recently wrote commentary on the new Reform prayer book.

Wonderful story, Edward. I’m glad the seder you attended this year was soulful and beautiful. They can certainly be that, but they can also seem boring and interminable (especially to a child). I’m sad that you grew up without any knowledge of all the wonderful Jewish rituals that are part of your heritage. As I said in my story, even though I mostly don’t believe in god, the ritual is important to me.

Thanks!

What a lovely, bittersweet commentary. Thank you for sharing this story. I come from a Conservative Jewish family but drifted for a long time and returned, in my 40s, to a Reconstructionist synagogue. Inclusiveness to Jews and non-Jews combines with deep learning of traditions there.

Thanks for the kind words.

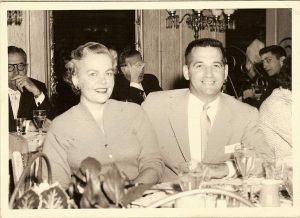

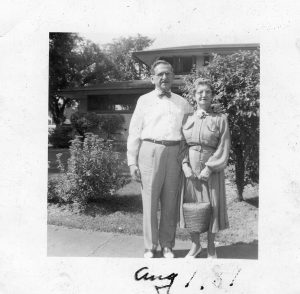

Your parents made quite the handsome couple! Thanks for sharing a beautifully written personal experience and the value to be found in many faiths.

It’s amazing to me how similar our religious upbringing was. I had a Jewish mother who became baptized as Christian in high school to presumably spite her Jewish parents, and then had my brother and I baptized as Christian when we were young children to presumably spite my non-religious (at the time) father, after their separation. I attended many different Christian churches, youth group, Bible study, Sunday school, and later Jewish temples. In my experience, African-American and Jewish were the most welcoming. I too have connected more with my Judaism as an adult and longed for a Jewish upbringing, but also found man-imposed dogma troublesome. While I value all faiths, I resonate with Nature, Art, Science, and Math, more than anything else. The energy and matter that flows through the universe and connects us all is the most spirtual thing I can fathom.