Except for a couple of easy day hikes in the wilds of New Jersey with the Scouts, I’d done practically no hiking at all.

Read More

Made for Walkin’

Except for a couple of easy day hikes in the wilds of New Jersey with the Scouts, I’d done practically no hiking at all.

Read More

Retrospect – A Moment Of Unexpected Kindness

By Kevin J. W. Driscoll (c) 2025

Reflecting on my life, filled with the highs and lows that have shaped me, there’s one memory that stands out as a moment of unexpected kindness. It’s a moment that occurred in the bustling heart of Boston, where the charm of the old blends seamlessly with the pulse of the new.

It was a cold winter evening in the late 1990s, and the city was cloaked in a thick blanket of snow. I had just left my office at the tech company where I had spent many long hours, pushing the boundaries of innovation. My marriage had already unraveled, and the solitude of my apartment was a stark contrast to the life I had once envisioned. The festive lights of Christmas did little to warm my spirits.

As I trudged through the snow, my thoughts weighed heavy with personal and professional troubles. I remember the feelings of tightness in my chest and the churning in my stomach and the streets, usually buzzing with the vibrancy of life, were subdued under the weight of the snowfall. I stopped by a small, unassuming church, its doors open wide despite the cold. As an Irish Catholic, the familiarity of the church provided a sense of solace, even if my faith had wavered over the years.

Inside, the warmth was a welcome reprieve from the biting cold. I found a pew and sat down, letting the quiet envelop me. There were only a few other souls scattered around, each lost in their own world. After a few moments of reflection, I noticed an elderly woman struggling to light a candle. Her hands trembled, the years clearly etched in the lines on her face.

Without thinking, I approached her. “May I help you?” I asked gently. She looked up, her eyes filled with a mix of surprise and gratitude. Nodding, she handed me the candle and the match. I lit the candle for her, placing it carefully in the holder.

“Thank you,” she whispered, her voice quivering with emotion. “My husband passed away last year, and I come here every evening to light a candle for him.”

Her words resonated deeply with me. In that brief moment, our lives intersected, and the weight of my own troubles seemed lighter. We shared a conversation that spanned memories of lost loved ones, the comfort of faith, and the quiet strength found in unexpected connections.

As I left the church that evening, my heart felt a bit warmer, my steps a little lighter. That moment of unexpected kindness—a simple act of lighting a candle—had a profound impact on me. It reminded me that even in the darkest times, there are glimmers of light, acts of kindness that can rekindle hope.

Looking back now, I realize that it was these small, human connections that truly defined my journey. The woman in the church, with her trembling hands and warm smile, taught me the enduring power of kindness. It’s a lesson that has stayed with me, guiding me through the ups and downs of life.

In a world that often feels disconnected, moments like these remind me of our shared humanity. They show me that kindness, no matter how small, can have a lasting impact. And so, as I reflect on my life, I cherish that cold winter evening in Boston—a moment of unexpected kindness that continues to warm my heart.

–30–

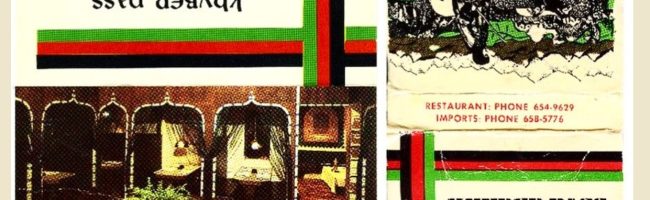

Cyrus, Darius I, Genghis Khan, Mongols, Sikhs, Afghans, and British all crossed or vied for the Pass. Still to come would be its incarnation as part of the “hippie trail” to India, and its role as a supply route for the war in Afghanistan.

Read More

I am heartbroken over how the pandemic impacted my grandchildren. What they lost can never be fixed.

Read More