The word “prejudice” derives from the Latin word “Praejudicim” which means “prior judgment”, or a preconceived opinion not based on actual experience. The following is an example of “post-judgment” based on actual experience.

Read More

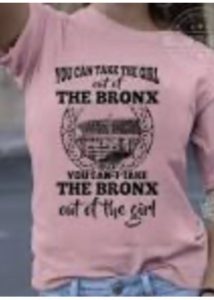

Bronx Girl

Bronx Girl

“The Bronx? No thonx!!” wrote the poet Ogden Nash.

As a kid growing up in the Bronx I didn’t get it, I didn’t realize my borough had a bad rap, and I certainly wouldn’t have understood why. The Bronx was my home and I loved it. (See Parkchester, Celebrate Me Home)

I even went to college in the Bronx, but then grad school and marriage finally took me out. But although I was then living elsewhere, I spent four decades of my working life commuting back as a public educator in Bronx high schools.

And although there may be some degree of rapport among all folks who discover they’re from the same hometown, I contend there’s a special bond among us Bronxites. We seem to share an unpretentiousness, a true grit, and of course that Bronx accent.

And one thing we all know – Ogden Nash was dead wrong!

– Dana Susan Lehrman

Cincinnati

Cincinnati

The great African American baseball legend Jackie Robinson was subject to unimaginable prejudice. Teams would bring up their Southern minor leaguers to taunt and insult him.

One day during a game in Cincinnati, a border town to the former slave state of Kentucky, Robinson’s Dodger teammate, Louisville native Pee Wee Reese walked over to first base and put his arm around Jackie.

Quite a gesture for a Southern gentleman, and that day the haters shut up.

The writer with unnamed Retro admin.

– Danny L, guest writer

From my Parents to Me to my Kids and Grandkids

While prejudice takes different forms in different eras, I fear it never really leaves us.

Read More