Could someone do that, steal who you were, and why would they do that?

Read More

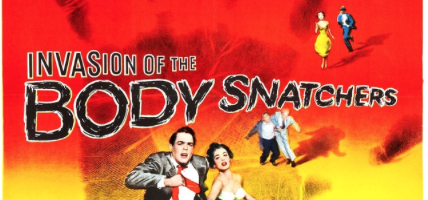

Body Snatchers

Could someone do that, steal who you were, and why would they do that?

Read More

"The king is pregnant." C'mon, what's not to love about that sentence?

Read More

Growing up in a small mining town in California’s Mojave Desert, we didn’t have access to a lot of variety when it came to grocery shopping. But my mom, in true post-World-War-2 fashion, was an enthusiastic supporter of every new thing that came on the market. So despite our little store’s limited potential, we kids sampled the best that America could offer in ingenious new foods.

Was it convenient? It landed in Mom’s shopping cart. Was it fast? She was on board. If Uncle Ben could make rice cook in half the time, that’s what we were having. Aunt Jemima offered pancake mix that already had all the stuff included; you just added water. Were Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben married? It seemed likely. Was Mrs. Butterworth a distant relative, or a little something-something on the side? You had to wonder.

Dad didn’t get involved in the kitchen very often (being the outdoor barbecue expert), but he seemed as pleased by these fantastic new time-saving foods as Mom was. As a Marine accustomed to eating Spam, Dad was more than happy to see the green Jello salad with its suspended bits of fruit cocktail, or the orange jello mixed with cottage cheese. It was colorful, it was fun, it doubled as a dessert, and despite its rather low-rent image now, there was no meal Jello could not brighten.

The novelty of Jiffy-Pop, the ease of mixing up Tang orange drink, outweighed any lack of taste in those years. No one expected Tang to taste like fresh-squeezed orange juice. It was more about saving labor. Who wanted to squeeze a bunch of oranges?

Many of Mom’s favorite products of the 50’s and 60’s later fell out of favor, to be replaced with new trends in cooking (I was glad to see the most frightening thing in the kitchen – the pressure cooker — go to the garage). No more canned strawberries; no more boiling vegetables till they were soggy. But Mom retained her love of the newest and latest all her life. She had no less than six Swiffer products in her pantry at last count. And she passed along her embrace of American ingenuity to her daughters, who now squirt Crystal Light into their water bottles and are always ready for the next new thing.

This guy Heinlein could really tell a story.

Read More

Once upon a time long, long ago, long before words like gluten, trans fats, cholesterol and diabetes were part of our everyday conversation there were Oreos.

Read More

My mother was insecure in life and insecure in the kitchen. Having me around made her nervous, so I was forbidden to watch. I didn’t learn to cook in her kitchen…a story for a different day. With her limited cooking skills, she cooked the same menu every week: Swiss Steak on Monday (barely edible – an insult to the neutral nation of Switzerland), some sort of chicken on Tuesday, spaghetti on Wednesday, meat loaf on Thursday, standing rib roast for Shabbat on Friday. Sunday we either brought in deli or she made her company meal of brisket and had relatives over.

She had learned to cook from her older sister’s housekeeper; I have some of her recipes. The spaghetti sauce is pretty good. She prided herself on her brisket, which I’ve come to understand was dry and not flavorful. But that was her company meal, served with canned peas and scalloped potatoes. This particular Sunday, she had my father’s oldest sister, my Aunt Pauline and Uncle Harry over. We ate in the dining room with the good china and nice linens. My mother made a careful plate with a few slices for each person at the table. But Uncle Harry had an appetite and asked for more. Mother hadn’t counted on that. She had only cut and cooked so many slices per person…no extra servings. Harry was quite upset and told her so in no uncertain terms. This was not the hospitality he was accustomed to. I was a teenager and sat quietly, absorbing the lessons of gracious hosting, even when offering dry brisket. It was a lesson not lost on this young one.

Baking Digger bread had only one stipulation — you had to give it away for free.

Read More

At Burger King, we ate with our hands!

Read More

I started cooking because I was hungry. In fact, I'm still hungry—all the time.

Read More

At the time, in 2006, it seemed a promising idea. I had just retired (early) from a long career at Stanford. One is eligible to retire when age plus years of service add up to the magic number 75. Having started fresh out of college and worked straight through, my relative youth was augmented by many years of service, and at age 49 I bid full time work adieu. My new beginning was a launch into the waters of the then-emerging world of online retail.

My college roommate has always answered the siren call of wanderlust, so my husband and I joined her for a trip to southeast Asia. While there, she and I were much impressed by the handiwork of local women’s craft guilds. Hand loomed silk, and objects made in silver, are a particular regional specialty. Once back home, we plotted and planned, extended contacts made in Cambodia, and launched an online store. We named the company RH Pumpkin, combining our last names and the beautiful silver pumpkins that were a signature item in our retail line.

The fun part? Sourcing and choosing the products – beautiful handloomed scarves and pillow covers; silver boxes of all description; paintings on silk; Christmas ornaments (what did the Cambodian artisans think about those orders?) Photographing the items for our website. The less fun parts? Managing online shopping cart solutions before those were simple plug-and-play, dealing with customs, and managing inventory in two separate locations. The business of business is to make a profit, and since that didn’t transpire to the level we envisioned, we eventually shut down operations.

Nonprofits have picked up the idea of supporting women’s craft collectives globally and we salute their success. Third career anyone?