She stared at me, burst into tears and ran across the street and into her house. I was surprised at how powerfully she reacted.

Read More

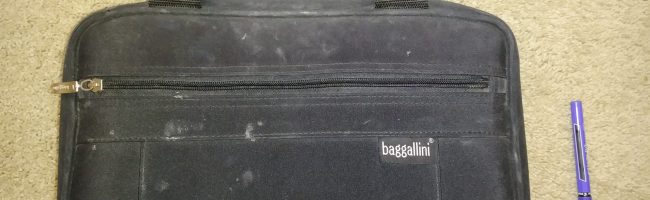

Go Bag for 40 Years

The bag has been with me any time I leave the house over night ...

Read More

Irreplaceable

From 1985-2000 I was rarely without my diaper bag. There was only one time in all those years that I took a trip and forgot it.

Read More

Cool Water

I’m not really thirsty til I realize

To my surprise and horror

That I’ve left the house without

My HydroFlask of water

Cool clear water (water, water)

I try not to panic but I find it hard to swallow

Will tomorrow ever come

I mean what I am to do

without water

Cool clear water (water, water)

Cuz what if there’s a pileup and

I face the the barren waste without

cool water

Wait…I feel a rumble beneath my seat!

It’s a plastic bottle I’d plum forgot to toss

Water (water, water)

Warm, sweaty water

With appreciation and apologies to Bob Nolan, and the dozens of artists who recorded his song Cool Water. And now, for your listening and viewing pleasure, from the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs…c’mon, sing it with me now: