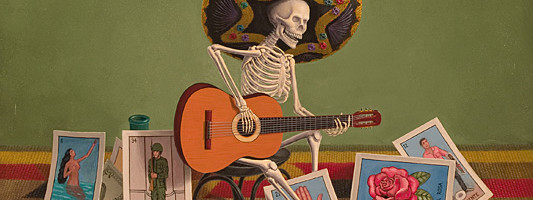

Some say death can be your ally. Yeah, maybe…

If you’re an Inuit shaman or a Yoruba priestess. Some days I can dig it. Mostly I doubt that death teaches us anything.

Today marks the year-one anniversary of ZL’s death. I first met Z when she ran into a theater rehearsal and shouted “they’re gonna put artists on a salary!” She was right. For five years, hundreds of us — filmmakers, theater artists, muralists, musicians — collected a paycheck and benefits for doing art in America. Impossible? No. Thanks to Z, we all applied for the program. Oh, the stuff we accomplished.

ZL lived in a Northern California commune through her 20s. We’re talking serious close-to-the-land self-sufficiency with a righteous point to make — this system sucks; we’re gonna build a better one. If you don’t mind wood stoves, kerosene lanterns and outhouses, they succeeded. When she returned to San Francisco, Z lived on Dolores Street in a rangy pullman apartment that logged in more traffic than the Bay Bridge.

I knew Z best from working with her in the Pickle Family Circus. I put the band together, Z did advance work (we toured a lot), juggled, and worked as a roustabout. Boundless energy, stubborn positivism, and gallons of coffee gave the woman superhuman powers. When stricken, Z didn’t appreciate her condition; it pissed her off to be dying. No apparent lesson to be learned there.

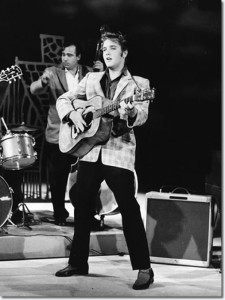

HM was the next to go. He was one of my few male friends in Los Angeles. Guys. Most of them don’t age sociably. HL did. He was an exquisite guitarist and songwriter born in Boyle Heights when the community integrated — half Jewish, half Chicano. H was half Jewish, half Chicano. Brooklyn Avenue became Cesar Chavez Avenue and everybody in the ‘hood thought it was cool.

HM told amazing stories, had a great sense of humor and made me laugh, showed me where to buy the best guitar, get these special strings. H could play anything. We both sang and sounded great together, rarely rehearsed. We already knew the same tunes. We could play “Don’t Think Twice” as a polka and make it swing. H bailed because the cure grew worse than his disease. Lessons? H was wiser, funnier, and a better musician when he was alive. Dead, he’s just not here anymore.

HR played tenor and drove a cab. Born in Detroit, H split after college, came out to San Francisco. All time I knew him (decades), H wore a perennial beard and a black Greek fisherman’s hat.

I met H in Winter Sun, my first electric band. He came across to play with us in the Pickle Family Circus band. He was the calmest adventurer I’ve ever known. He’d say ‘why not’ and try anything. H loved jazz, his friends, and marijuana until he dropped it. He excelled without need for recognition.

When H learned what assaults he would have to endure to gain a few more months, he said ‘no thanks.’ His decision seemed very much in character. I guess that means he died the way he lived.

DL was my oldest friend. We rambled, raced, rocked and rolled together from fourth grade through high school. D was born in the UK but emigrated when his old man, a British colonial attache in North Africa and graduate of the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, decided he could not tolerate the socialist disaster that befell his precious bloody England when they booted Churchill out of Number 10 Downing. DL’s dad snatched up his wife and child and fled to our small Massachusetts town.

DL was smart but unpopular. His unorthodox intelligence suffered from the censorship of traditional education and an intolerant township elite. D grew to be an inspired liar and learned how to not give a damn. He did not-give-a-damn well, even flamboyantly. According to the club, D had already boarded the train bound for purgatory. I always liked the guy. We hung out in high school and I don’t think he ever crossed me.

I lost track of D after high school. After my old man died, my mother moved away and I lost track of everyone in that little town. David and I picked up at our 40th high school reunion, the first we had ever attended.

DL may have gone to purgatory, but he returned as a fabulously rich man. He restored a house on the water in Duxbury with a ship chandlery from 1820 still outfitted in the back room. A vineyard ran down a gentle slope to Cape Cod Bay. He refitted an elegant, seaworthy 70-foot, ketch-rigged schooner from the Gilded Age and built a hilltop palace on St. Lucia.

DL and I had reached two different destinations, often traveling the same paths, but not together. I had been a revolutionary, D a hippie entrepreneur. We disagreed on everything. We didn’t give a damn; we loved each other unconditionally. I barked back at his smart but cynical worldview. He understood and supported my writing, the worlds I choose to explore. I marveled at the generosity of his extravagance.

D only shined me on one time. He told me he was fine when he wasn’t. He told me not to bother visiting him, he’d be back on his feet by summer. In reality— like HR — DL pitted the cure against the cause and the cure lost. All I learned from DL’s death is how much I miss him.

- * * *

Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe death can be an ally, a mentor. It’s certainly a reality. But as the losses increase, life begins to feel like war. And — as with war — there are no lessons to be learned from death. Perhaps I’ll learn something after the fact. In the meantime, I love life too much to seek instruction.

# # #