Setting the menu for potlucks, before anything else, I was asked to bring my mother’s lasagne. Not some vague ‘meat course’ or ‘dessert’ but specifically The Lasagne. I thought, Cool, the kids love her lasagne.

With a bit of distance, I realise they were just trying to ensure that I didn’t bring something untested, or tested but revolting. Like her famous Irish Pizza, made with canned everything and a potato crust. It was’t so much that anyone loved her standard-issue lasagne, but it was safe.

In my house, food was needed, not wanted. A practical skill, not an art-form. Mealtimes were for getting together; what we ate was irrelevant. Menu planning began with the meat, which ranged from bacon gravy – one of my favourites, because the next thing was biscuits to put it on, which I got to make since my mother’s biscuits were famous as doorstops – or chipped beef on toast, to fancy things like chicken thighs with tomatoes and onions.

Starches came next, if not integrated into the meat course. Potatoes or pasta. Then a veg, like canned peas – my mother’s favourite story, a dinner at her home when the cook was gone and my grandmother served burnt canned peas, from which my mother thought to divert attention, in her 12-year-old way, by saying, I just love burnt peas! – or, in the gourmet, post-Korean-war days, frozen broccoli. Salad, when we had it, was an afterthought – as likely to be jello and canned fruit as anything with lettuce.

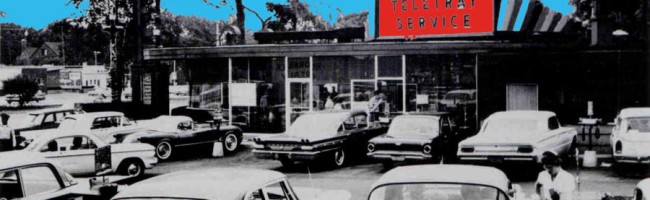

Granted, the ’50s were not, in general, food heaven. Rationing, along with The Depression, was blamed for everything from avarice and jealousy to poor cooking skills. The great advances of the prosperous post-war were packaged foods, frozen things, exotic experiments like canned mushroom soup over frozen Greenlake beans. Nothing related to what we now would call ‘food’ or ‘cooking’.

Of wartime rationing – deprivation’s gold standard, called upon to justify any later culinary lapse – I remember most the stolen delights, not the daily scrimping. Breakfast at the Canterbury Hotel on Sutter St, where we lived when we first came to the city, was a treat. My older brother, 4, and I, 2, were allowed to go down to the dining room for breakfast while mom nursed and dressed the baby.

Oh, was it grand! The Canturbury was crowded with resident widows. Children were rare; we got terribly spoiled, steadfastly trained in the efficacy of shy looks and blinking lashes. When I climbed up on my pile of phone books and snuggled up to the table, I gazed with rapture at my dish of hot oatmeal, ringed by cream-pitchers, real cream, sent over by the dames of the hotel. I breakfasted every day on islands of congealed oatmeal floating in lakes of cream. Creammmmmm. We were used to doing without even milk most days – what a princely treat this was! And why, perhaps, I have ever since felt like a prince.

At home in later days, the prince, with the rest of his so-called ‘family’, ate simply. Mom was raised in a house with servants. Her mother never cooked, nor did any of her mother’s female relations going back generations. Her dad’s mother, a child of potato-famine immigrants who lived with them, was a spinster teacher from Ohio who married an old man in Missouri – but the cook cooked and not she. Our dad came from a Mountain family where the men just ate and complained. He knew good biscuits, but could not make them. The best he could manage was the ’50s male standard – barbecued steaks or a roast in the oven. On Sundays, when.

So what did I know of lasagne? Or good cooking?

Later, out on my own, I went through a phase in which I felt it necessary to offer visitors stuff like salmon swimming in aspic in order to distance myself from my food-negative past. Then I discovered the trick was in marrying a chef, in my case a Sicilian with generations of experience.

Now, when we have lasagne, it’s made with sliced aubergines, because he doesn’t eat pasta, and so full of flavour it makes me laugh. The neighbours request it, but not from fear of other dishes. From addiction.