I didn’t eat for several years.

My mother prepared dishes that were unable to go down my throat, dishes consisting of soggy and over-cooked frozen vegetables, dishes with cream corn from a can–not even worthy of bluegill bait–and shriveled peas, dishes with roast beef so over-cooked that it would not only suck out all the saliva in your mouth like a stale chicharon, but if left in too long, would start to collapse the entire bone structure of your cranium.

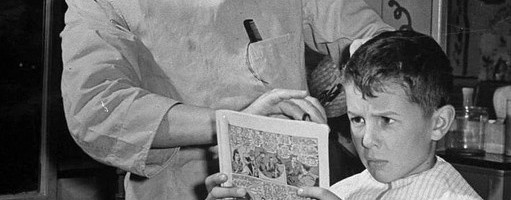

My father’s over-used response was the same every time: “Son, you don’t have to like it, you just have to eat it.” And if you didn’t eat it, you sat there until bed time, all the while hearing your friends outside screaming and laughing and playing. (I once responded with, “Would you eat dirt if you didn’t like it?” That was not a good outcome. I think he thought I was talking about his wife’s cooking, but I was really just using dirt as an example of something that doesn’t taste good to most humans. So shoot me for trying to reason.)

My first attempt was cliché, stuffing as much into my mouth as possible, asking to be excused to use the bathroom, and then spitting it out in the toilet. That attempt failed–not the spitting out part, but the keeping-from-being-detected part. I got a whippin’ with a leather strap, and that was without proof. I learned my lesson: be smarter than the warden, and don’t get caught.

I tried everything: packing the chewed and compacted food way back into my mouth in places I didn’t know even existed; secretly keeping extra napkins with me to discard the food, bundling them up and shoving them down my underwear until she noticed inappropriate stains, hiding them in my pockets until my pants started smelling like oil & vinegar, packing them in my socks until she noticed that the stains weren’t from dirt.

Every night, before I was excused, I was required to go to the kitchen so my mother could interrogate me, followed by a full-body search, ending with her digging her finger throughout my mouth as if I were smuggling in drugs. I even tried the dog–which actually worked for a short while–until I got lazy and forgot to wipe his mustache. Dried tamale pie on a wired-hair mutt can be a dead giveaway to a discerning mother whose sole purpose in life was to detect any wrongdoings.

Once in a lifetime, every human is blessed with nothing less than a miracle, an end-of-the-rainbow find, if you will. Struggling through my refining process, almost at my wits end, I discovered a board (or shelf) under the table, running the full length. In carpenter’s terms, a 1″ X 6″. In my terms, a “magical” shelf, sent from heaven, letting me know that God is good, God is merciful, and the world is just.

From that point forward, it was a slam dunk. I’d wait for everyone to leave the table, as usual, then I’d grab handfuls of whatever was on my plate, cupped it, turned it upside down and smacked it down on top of the magical board like a wad of clay. At night, when everyone was asleep, I’d scoop the substance off the shelf and into napkins, walked out into the back alley, and slung them into the neighbor’s yard. Even though it was always dark, I could still see my frozen vegetable and tamale pie grenade, unfolding in mid air like a parachute, the particles dropping first, then the white napkin following, as if in relief to get rid of its package. I launched them into a different backyard every night to avoid suspicion.

My mother thought that I was eating better and/or her cooking was getting better. The Warden thought I was maturing, owning up to my eighteen-year sentence. But the truth was, I beat the system.

As time went by, I got lazy, and sometimes I neglected to get up in the middle of the night to throw food grenades. Until finally I just stopped altogether. What the hell, the shelf was as long as the table, endless.

Years later I did start eating everything on my plate and forgot about the magical shelf and how it saved my life. Until one day. My parents decided it was time to refinish the table. When they took it apart they could not, for the life of them, figure out how these concrete mounds got formed under the table. A fuzz like mold covered them, further concealing their true identity. They brainstormed for awhile before arriving at their Aha! moment.

Until your eighteen-year sentence is up, you are never too old for an old fashion whipping.