The old variety shows had something for everyone. If you didn't like one act or segment, there would be another in minutes.

Read More

Unity Through Variety

The old variety shows had something for everyone. If you didn't like one act or segment, there would be another in minutes.

Read More

I was never a lover of Ed Sullivan (except for the famous Beatles performance) or Carol Burnett, but boy did I enjoy Rowan and Martin and The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.

Read More

I have already written about losing my parked BMW in 2003 (Finding the Car). Therefore, I will go in a different direction today.

During the summer of 1971, I worked as a counselor at the Jewish Community Center Day Camp, situated next to my temple in Oak Park, MI, not too far from my home. I was a rising college sophomore, 18 years old. The head counselor, Harold, had graduated from University of Michigan, was in law school and married to the cousin of one of my closest friends. There were two other college-aged counselors and two junior counselors in high school. We had the “Safari” group: 12 year olds who weren’t allowed to go to the overnight camp run by this organization for various reasons (usually they weren’t mature enough, or had some emotional problems). We had access to a bus with a driver and took them on trips each day (to a Vernor’s Bottling Plant, Greenfield Village, horse-back riding). On Fridays we went to the beach at a big local lake. It was a fun program and the kids were usually fine.

Early in the summer, Harold announced he wanted to fix me up with one of his fraternity brothers, a groomsman from his recent wedding. Mel had broken off his own engagement and was looking to date again. I was dating my close friend’s brother a bit; nothing serious. I told Harold it would be fine for Mel to call me.

Mel lived in Windsor, Ontario, worked in a plant in Windsor that summer to earn some real money, was also in law school, in Fredericton, New Brunswick; very far away. He had an older brother who lived in Southfield, MI, a neighboring suburb to mine. That could be convenient. Also, Michigan was on one of its “no daylight savings time” kicks, so Mel and I were not in the same time zone.

Mel called immediately and we chatted several times. We had long, lively conversations. He was charming and funny on the phone. I remember we laughed a lot. That was always a good sign. Soon, he asked me out. He had tickets to see a pre-Broadway concert version of “Jesus Christ Superstar”. I was all-in. I remember just what I wore that night: the flattering peach pant suit that I wore on my first day at Brandeis.

For some reason, my parents had gone out before Mel came to pick me up that evening (unusual; they would normally want to meet a new guy before our first date), so I was home alone when I opened the door and saw the darkly handsome man with the mustache in front of me. He took my breath away. I thought, “This is what Rhett Butler should look like (Clark Gable may have done it for an older generation, but was never MY ideal Rhett Butler)”. I remember we had a lovely evening, really enjoyed the show, never lacked for conversation and he had me home at a reasonable hour, asking if he could see me again. I guess he also liked what he saw when the door opened, and enjoyed his evening.

We dated a lot for the remainder of the summer, going to movies or out for a meal, as his schedule permitted (since he was coming from a different time zone). Sometimes, he’d stay over at his brother’s house, rather than driving back to Windsor, though at the time it was easy to do – the border was completely open. My family used to go there for dinner, no passports required.

But if his brother (who was a doctor and married) was home, it was difficult as the relationship developed, to find a place for quiet intimacy, so his car was it. I don’t remember the locations we’d drive to, but we often “parked”; making out in his car. This was the era of sexual freedom and the relationship soon progressed beyond just “petting”; it got hot and heavy. We both really liked each other, even knowing that it would be difficult to keep up a long-distance romance. He took me to meet his brother, who was polite to me (at that point, I was about 5 years younger, which was a fairly large age gap, but I carried myself well).

Being intimate in a parked car wasn’t fun. It is cramped and one worries that someone will discover us. But we couldn’t help ourselves. The summer wound down. I went back to Brandeis. He went back to New Brunswick. We wrote a bit. I met Bob. Mel faded out. Some years later, my girlfriend’s cousin divorced Harold. I heard Mel settled in Toronto after law school.

While traveling to Toronto on business years later, I looked him up in the phone book (those still existed). He had become a prominent lawyer; I did not call. I was happy for him. Seeing his name brought up pleasant memories from that one summer. We had such a good time together, even if we had to “park”.

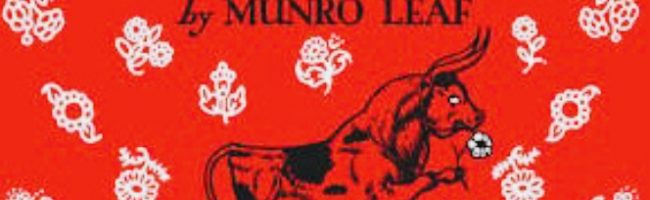

Ferdinand

“Once upon a time in Spain there was a little bull and his name was Ferdinand.”

So begins one of the most cherished children’s books of our time, and my own childhood favorite. The Story of Ferdinand, written by Munro Leaf and illustrated by Robert Lawson, was published in 1936 while across the Atlantic the Spanish Civil War was raging.

But as a child I was oblivious to the book’s anti-Fascist, anti-violence polemic, nor attuned to its message of acceptance for children with differences.

And I certainly didn’t know that Hitler had ordered the book burned as degenerate literature, or that in Franco’s Spain it was banned as anti-Fascist propaganda until the death of the dictator decades later.

And I don’t think I was bothered at the time by the concept of bullfighting, perhaps I was too naive to realize that the bull always loses. I simply loved the book for it’s sweet, funny story, and it’s delightful illustrations. But decades later on a trip to Seville, and against my better judgment, I went to a bullfight that haunts me to this day.

Of course you may know the story – unlike the other young bulls who love to run and buck, Ferdinand is content to sit under a “cork tree” and smell the flowers. And when by a serendipitous and humorous twist of fate he’s taken to Madrid to fight in the bullring, he catches the scent of the flowers in the hair of the lovely senoritas. He then sits down in the middle of the ring to enjoy the smell, ignores the provocations of the disgruntled matadors, and as he won’t fight, he’s sent back home.

Ferdinand’s mother worries about her unusual progeny, but she sees he’s neither lonely nor unhappy, and so leaves him to his peaceful pursuit because – as Munro Leaf so wisely tells us – “she was an understanding mother even though she was a cow”.

What a better world it would be if we all stopped to smell the flowers, like that little Spanish bull named Ferdinand.

– Dana Susan Lehrman