In the years when I was growing up, which were the early years of television, my family watched a lot of TV together. My dad had his recliner, just like Archie Bunker, which no one else was allowed to sit in. My mom sat on one end of the sofa to his right, crocheting. The boys claimed the other chairs and our cocker spaniel Rusty, who howled to the Final Jeopardy music on Jeopardy, had his place on the carpet.

There weren’t a lot of choices on TV in the 1950s and ’60s – just three networks and three local channels, which made it easy to remember which shows appeared on which nights and in what order. We watched a lot of family sitcoms like Leave It to Beaver and My Three Sons, and nearly every night one of the variety shows that proliferated on 1960s network TV. Saturday you had Jackie Gleason and later Carol Burnett. Tuesday was Red Skelton. Thursday was Dean Martin. And from 1948 to 1971, Sunday nights belonged to Ed Sullivan.

There weren’t a lot of choices on TV in the 1950s and ’60s – just three networks and three local channels, which made it easy to remember which shows appeared on which nights and in what order. We watched a lot of family sitcoms like Leave It to Beaver and My Three Sons, and nearly every night one of the variety shows that proliferated on 1960s network TV. Saturday you had Jackie Gleason and later Carol Burnett. Tuesday was Red Skelton. Thursday was Dean Martin. And from 1948 to 1971, Sunday nights belonged to Ed Sullivan.

Sullivan was the unlikeliest of TV hosts. Originally a syndicated newspaper columnist, he had absolutely no charisma and no performing talent of his own (“Ed does nothing, but he does it better than anyone else on television,” cracked comic Alan King) and was often mocked for his stiff-shouldered posture and stilted speech (“We’ve got a really big shew for you tonight”). He earned the nickname Old Stoneface. But he had a great eye for talent, and a keen sense of timing. “Who was hot?” “Who was about to get hot?” Ed always knew.

Elvis Presley on The Ed Sullivan Show. The network insisted on shooting him from the waist up.

Today he’s best remembered for introducing Elvis Presley and The Beatles to American audiences, but in fact Sullivan booked the people you most wanted to see every single week, year after year. Watching his show, you got the sense of being part of a collective national experience — of having your hand on the pulse of popular culture. Anyone with a hit record went on Sullivan, anyone riding high in a Broadway smash. And being that it was a variety show in the fullest sense of the word, you got a stupefyingly wide range of entertainment. Alongside the A-list stars, there were Chinese acrobats, plate spinners, folkloric dancers and the Marquis Chimps. Into the mix came jazz, classical music and ballet; cameo appearances by popular athletes; novelty acts like the Italian mouse Topo Gigio and Spanish ventriloquist Senor Wences, who drew on his hand and made it a puppet.

Jackie Mason

You had stand-up comics, most of whom were Jewish: Jackie Mason, Myron Cohen, Jack Carter, Totie Fields and Joan Rivers. And, since the show originated in New York in the same Broadway theater where Late Night with Stephen Colbert is taped today, you got a taste of the grit and moxie of native New Yorkers. You heard those pungent accents – I’m thinking of Jerry Stiller, a Jew from the Lower East Side, and Anne Meara, his Irish-American wife from Long Island — that came directly off the streets and declared unambiguously, “I’m a New Yorker.” Sadly, those accents are disappearing.

Alan Jay Lerner, lyricist of “My Fair Lady” and “Camelot.”

I grew up loving Broadway musicals, and I have Sullivan to thank for that. I remember Lucille Ball coming on his show to sing “Hey, Look Me Over!” from her short-lived musical Wildcat, and dazzling Gwen Verdon offering “If My Friends Could See Me Now” from Sweet Charity. A spot on the Sullivan show could rouse a sleeping box office, create a hit where an early closing notice seemed imminent. In his memoir On the Street Where I Live, the My Fair Lady lyricist Alan Jay Lerner wrote that when Camelot opened in 1960, “Word-of-mouth was not good and the chances of recovering the investment seemed infinitesimal.” When Sullivan announced plans to salute the fifth anniversary of My Fair Lady with a full-hour tribute to Lerner and his songwriting partner Frederick Loewe, he agreed to include four songs from the struggling Camelot at the back end of the program. “Ed, one of the most gracious gentlemen in television, gave us carte blanche,” Lerner wrote.

Julie Andrews, Richard Burton in “Camelot.” A Sullivan appearance turned their sleeping show into an overnight hit.

The following morning, Lerner was awakened by a phone call from the manager of the Majestic Theatre: After weeks of sluggish box office, there was a line halfway down the block. Camelot became a solid hit, won several Tonys and ran for two years. There were probably hundreds of stories like that. The Sullivan effect was so deep and wide that a song in Bye Bye Birdie, “Hymn for a Sunday Evening,” playfully satirized his influence. The family of a teenage girl from Sweet Apple, Ohio, is about to make an appearance on the Sullivan Show, and they are so overjoyed that they burst into song: “Ed Sull-i-van! Ed Sull-i-van! We-e-e’re gonna be on Ed Sull-i-van!” Back then, he had the same level of clout and fame that Oprah enjoyed at her peak.

Lerner’s comments notwithstanding, Sullivan was a controversial and sometimes abrasive figure. “As the show’s producer, he took dictatorial control over every aspect of his production,” wrote James Maguire in Impresario: The Life and Times of Ed Sullivan. “In contrast to his persona as the reserved and respectful host, as producer he didn’t care who he offended, with the exception of a very few high-profile guests.” After a Sunday afternoon rehearsal, he would often cut or reshape a comic’s material, assign a different song to a singer or even drop a performer altogether if they didn’t “jibe with his gut instinct of what would reach the home audience.”

Sullivan with the recalcitrant Mick Jagger.

During those years of The Ed Sullivan Show, American entertainment wasn’t Balkanized the way it is today, meaning that every kind of act, irrespective of race, genre or nationality, appeared on the show “And now, right here on our stage,” Ed would announce, and bring on Diana Ross and The Supremes, or uber-diva Maria Callas, or Black comic Jackie “Moms” Mabley. When the Rolling Stones guested on Sullivan, CBS’s Standards & Practices office insisted they replace the lyric “Let’s spend the night together” with “Let’s spend some time together” – a silly sanitizing gesture that Mick Jagger derided by rolling his eyes during the live performance. I remember French chanteuse Edith Piaf making multiple appearances, each time in the same black dress and each time delivering her triumph-through-tears anthem “Milord”; and gospel queen Mahalia Jackson, another regular, breaking into a sweat and patting down the beads of perspiration on her face with an ever-present handkerchief.

Plate spinners on the Sullivan show. Ed offered variety in the fullest sense of the word.

Those are all vivid and fond memories. The Sullivan show was a weekly event in the life of my family, an every-Sunday-night ritual. When I look back, it’s significant that we watched it in real time. Nobody had DVRs or TiVo back then, so you couldn’t record a show; you couldn’t pause or rewind during a broadcast. That meant you had to be more focused, more present than the multi-tasking, smart phone-addicted TV watchers of today. It made the experience of sharing a favorite program — with your family, with the rest of America watching simultaneously — that much richer.

In March 1971, CBS foolishly decided to cancel The Ed Sullivan Show after 23 years and an astonishing 1,068 episodes. The network wanted to target the youth demographic with its greater potential ad revenue, and saw the Sullivan audience as old and staid. Ed was irate at being axed, and refused to host the additional three months of scheduled shows. The network ran reruns instead.

Television’s ultimate impresario lived another three years beyond his cancellation, dying shortly after his 73rd birthday on October 13, 1974. At St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, 3,000 people attended his funeral on a cold and rainy day, honoring a man whose personal manner was stodgy and uptight, but whose instincts as a host and tastemaker brought us decades of great entertainment. Television has never been quite the same since.

Television’s ultimate impresario lived another three years beyond his cancellation, dying shortly after his 73rd birthday on October 13, 1974. At St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, 3,000 people attended his funeral on a cold and rainy day, honoring a man whose personal manner was stodgy and uptight, but whose instincts as a host and tastemaker brought us decades of great entertainment. Television has never been quite the same since.

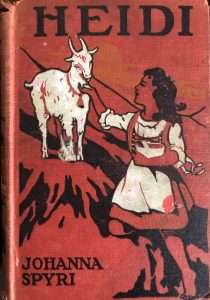

I still have a stack of some of the books that sat on my shelf as a child. I just can’t part with them. My very favorite was Heidi by Johanna Spyri.

I still have a stack of some of the books that sat on my shelf as a child. I just can’t part with them. My very favorite was Heidi by Johanna Spyri.