With apologies to Ms Franklin

Read More

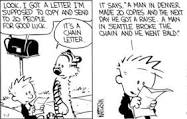

Chain, chain, chain retroflash

With apologies to Ms Franklin

Read More

A good childhood in the woods, a crippled frog

Read More

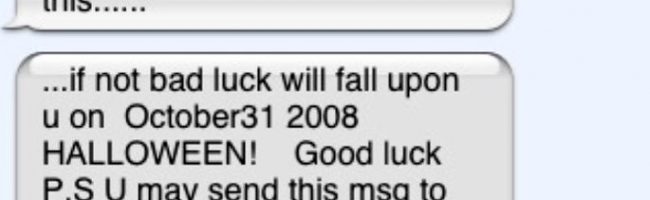

Chain letters were never my thing.

Read More

My Zuzu

I’ve written about my beautiful kid sister Laurie – my Zuzu – who died in 2015 at age 61 after a long and painful battle with MS. (See Take Care of Your Sister, Look for the Helpers – for Laurie)

Laurie was gifted, and at the time of her illness an NIH research biologist working on the genetics of cancer.

But her private life was quite tragic. Her husband Andy was always a very difficult and belligerent guy, and their only child, a beautiful boy named Michael is severely autistic.

When Michael was diagnosed at age 2, family and friends rallied in support. My folks were ready with financial and whatever other help they could give to see that Michael had the best special schooling, tutoring, therapy and other available interventions. But Andy very ungraciously refused all help and shunned any advice.

And then my sister’s MS diagnosis came on the heels of Michael’s, and to our dismay Andy again refused help and advice. He antagonized Laurie’s friends, basically forbade our visits, and insisted on keeping Laurie home when it was obvious she needed 24/7 nursing care.

My parents didn’t live to see my sister become ill – and for that I am grateful. But I was left with the unbearable burden of knowing she was suffering, both physically and emotionally, and I felt I had to intercede.

Laurie was living in another state, and I started researching legal steps there I could take, the medical and social services that could help, and the possibility of bringing her to New York to be near me. But my brother-in-law was her next of kin, not I, and Michael’s situation was another consideration, so I felt my hands were tied.

Then fate intervened, Andy suffered a heart attack at home, called 911, and the responders found my bedridden and incoherent sister in the house as well. She and Andy were taken to the same hospital, but Andy was soon transferred to a cardiac unit elsewhere.

By then Laurie’s condition was dire – incredibly Andy had stopped her neurologist visits and her medication thinking he knew best how to treat her. Seeing this, the hospital staff asked me to stand in as her temporary medical decision-maker which was possible while Andy himself was incapacitated.

Then I was asked to take the next step and petition the court to become my sister’s legal guardian, which I did. Thankfully Michael was able to become a resident in the county-run special needs program in which he had been a day student – a placement that has been a godsend as my nephew has gone on to thrive there.

Laurie spent several weeks in the hospital and when she was stable enough, we transferred her to a wonderful nursing home. There she spent two years under the care of an amazingly compassionate medical and nursing staff, and eventually a caring hospice team.

I’m grateful for the loving care my sister had during the last years of her life, but my greatest regret is that I didn’t act sooner, and it will weigh forever on my heart.

– Dana Susan Lehrman