We were put on a bus, blindfolded, and driven around country roads this way and that. At some point, groups of four were let out of the bus, given a map, and told to find our way back. We were all fifth graders in East Lansing public school and this was part of the curriculum for our week at Clear Lake Camp–an exciting and scary prospect for newbies like me. The blind drop-off was perhaps the most daunting.

At last it was our turn. My group of four stood apprehensively, abandoned in the middle of the dusty road, with an unmarked T intersection not far away and only woods and fields in sight. I looked at the map, and the solution seemed impossibly simple. If we just turned at the intersection, the road would lead us directly back to camp, maybe half a mile away. No one else had a better idea, so we followed my suggestion and were the first ones back.

Maybe that wasn’t much of a challenge, but over the years I have thanked whatever mix of genetics and evolution makes it possible to carry locations in my brain. Of course there is help from the position of the sun and visual landmarks like mountains and water, although I wouldn’t want to challenge a migrating bird or butterfly. Maps also help.

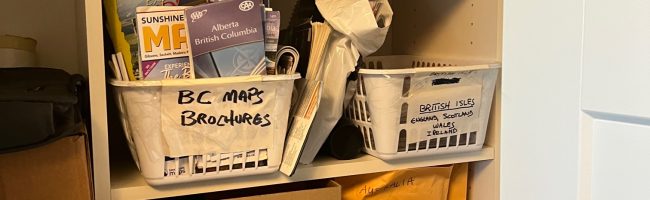

I feel an almost physical need to know where, geographically, I am–and for that matter, genealogically, metaphysically, astronomically and relationship-wise. Maybe it has something to do with a sense of control over the vastness of existence. One of the first things I want when traveling is a map, and I probably qualify as a “cartophile”. Everything from hand-drawn sketches to ancient maps of the world, from historic ordinance maps of England and Scotland to globes with past and future solar eclipses–the number of maps in my house is ridiculous. We once bought another suitcase to cart home a large atlas of maps from the 1600’s. The automobile associations also put out wonderful maps, as do local tourist services. Although Google and car GPS have forever changed how we access geography and directions, there is still nothing like a good old-fashioned map at the right scale with the critical information.

Pre-GPS, Sally and I were driving from the Sierra Nevada to the Bay Area as night fell. We were on some backroads, crossing the Central Valley, confident as we sped through the little towns toward I-5. Maybe we were talking. There were a few turns here and there, but we were both comfortably on the right road heading west, although it seemed that I-5 was elusively far. Suddenly, Sally asked if that little bar with the neon sign that we passed on the right didn’t look a lot like the one we passed on the left a half hour earlier? We tried to look at a map in the dim car light, tried to look for stars overhead, but it was clear that our inner maps were both 180 degrees off and we were steadfastly headed east. The more smug you are in your orientation, the harder it is to recalibrate. And how could we both have had our sense of direction fail us so? We were humbled.

In the end, we are not in as much control as we might like to think we are. But maybe that is why it is so satisfying when you set a course and actually end up at your goal.