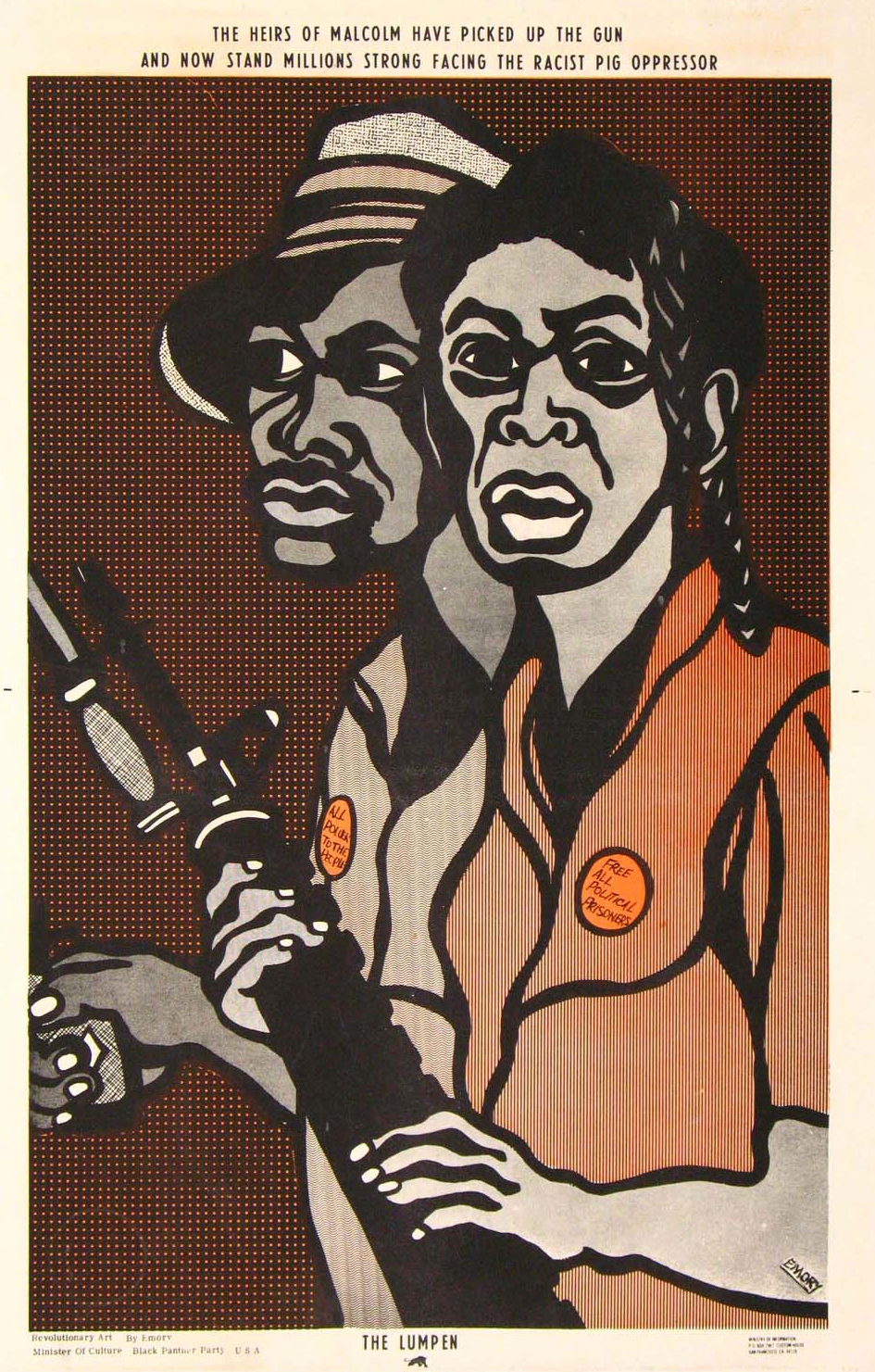

©emory douglas

My family left the federally funded G.I. housing project in Jamaica Plain, Boston when I was three years old. All kinds of people had visited us there, friends of my parents. Scientists and academics, union organizers, they came from China, Yugoslavia, and the Netherlands.

"We must all swim in the same sea. Right?”

We said goodbye to them all when we moved to a small New England town. There I came of age with the Kimballs, the Whitcombs, the Channings, and the Browns.

The first black person appeared in my school when I was in eighth grade. On his first day, the bus driver refused to let him board. Hearts pounding, my friend David and I rushed to the front of the bus and threatened to report the driver to the school principal. Grudgingly, he backed up and opened the door for the stunned child who had remained standing dumbfounded and confused beside the road.

The boy’s name was George, and he was the son of a military man stationed at nearby Fort Devens. He was the only black child in our school. Despite our ministrations, he only survived his brief tenure through shyness and solitude.

In high school, I attended a peace camp sponsored by the Quakers. This was during an intense, anti-nuke, ban the bomb era. World peace and civil rights formed the causes celébré of the time. Resource people from India and Mississippi spoke of non-violent resistance, and I soaked up the blues of Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, and Lightnin’ Hopkins from the guitarists who came north for New York for the two week country interlude. I began studying black history through the blues.

At 19, I joined a community action project in a Philadelphia neighborhood fragmented by race and bound by poverty. We struggled to bring our rage at injustice into this other America, but our only allies were the black women who would reach out to anyone who might help protect their children from the racism and economic violence that laid siege to their lives. We could not hold them.

After I graduated from a college that still segregated its students through gender apartheid, I argued my way out of military service and joined a theater company that threw itself into direct confrontation with a system that allowed the war in Vietnam to smother a war on poverty.

After I graduated from a college that still segregated its students through gender apartheid, I argued my way out of military service and joined a theater company that threw itself into direct confrontation with a system that allowed the war in Vietnam to smother a war on poverty.

This theater company created a minstrel show that hurled racism back at our own race, class and culture. We produced a commedia performance that twisted our profitable imperial conflagration in Southeast Asia into a bawdy and darkly ironic farce. Moliere with napalm.

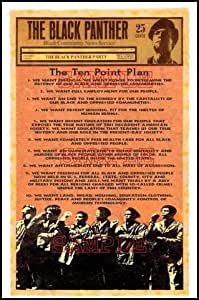

One day, Bobby Seale and “Li’l” Bobby Hutton (he was 17 and 6’3”) of the Black Panther party visited the theater company’s studio to explain the Panthers’ Ten-Point program. I was struck by how differently Seale and his young colleague saw the world. I knew they were right, but I was unused to the view through that lens.

“Most white people do not want black people to have power,” Bobby Seale told us. “They’re like children raised in poverty, who grow up thinking there’s not enough to go around. Not enough love, not enough money, not enough power. They can’t shake that childhood fear, that poverty paranoia, no matter how much money they have, how much luxury or comfort they live in, or how much status they command. Racism comes out of that same poverty paranoia.

“Most white people do not want black people to have power,” Bobby Seale told us. “They’re like children raised in poverty, who grow up thinking there’s not enough to go around. Not enough love, not enough money, not enough power. They can’t shake that childhood fear, that poverty paranoia, no matter how much money they have, how much luxury or comfort they live in, or how much status they command. Racism comes out of that same poverty paranoia.

“Now over the centuries the white man has learned how to use racism as a power tool. When you hold that tool in your hand, you don’t want to give it to anybody else. In our community, we have very little access to power tools. But if we want to protect our community, we have to exercise power.”

L’il Bobby took over. “And since they won’t give us any, we got to take the power. And we got to back it up with guns. Guns treated right, you understand? As tools. Tools for survival. Tools to deliver our message — stop killing black people. Stop murdering us. We want whitey to pay attention.” L’il Bobby grinned. “And there’s nothing that gets whitey’s attention like black people with guns.”

L’il Bobby took over. “And since they won’t give us any, we got to take the power. And we got to back it up with guns. Guns treated right, you understand? As tools. Tools for survival. Tools to deliver our message — stop killing black people. Stop murdering us. We want whitey to pay attention.” L’il Bobby grinned. “And there’s nothing that gets whitey’s attention like black people with guns.”

Bobby Seale took over again. I was struck by how easily they spoke in concert, in a swinging call and response. “But we also believe that exclusive black power just separates us and isolates us. Black power implies black economic power. We would have to establish a separate but equal black economy. If you study economy, you know you cannot extricate yourself from an economic system. You gotta interact with it.”

We sat listening, transfixed by this man. He spoke in strong, definitive tones, without pauses. He carried anger in his eyes, in the taut lines of his cheekbones, in his jaw, but he spoke with the ease of a person who is sure of his audience.

“So why are we here?” Bobby Seale didn’t wait for an answer. “As I said, we’ve seen your work. And we know you can travel light. So, we have come here to discuss the possibility of combining forces.”

L’il Bobby jumped in. “You might not know this. Most of you don’t. We’re trying to reach out to the white community and all people. We are not separatists. Like the Viet Cong says, we must all swim in the same sea. Right?”

We all nodded. Yeah, L’il Bobby was right. So right. And we felt at one with these two men.

Bobby Seale continued. “Any separation of the black radical movement from the white radical movement is arrogant and self-defeating. It plays into all that old Machiavellian shit — divide and conquer. We have two fronts we must fight on — racism and capitalism. The two are intertwined and we must destroy both. We can do that together.”

The whole room broke out in applause. Everyone stood, talking to each other, asking further questions of big Bobby Seale and little Bobby Hutton. I wished we had music to play. It would have been right. We decided together that we would write a series of portable puppet shows, the Gutter Puppets, that would talk about the Black Panther Party for Self Defense and its Ten Point Program.

The whole room broke out in applause. Everyone stood, talking to each other, asking further questions of big Bobby Seale and little Bobby Hutton. I wished we had music to play. It would have been right. We decided together that we would write a series of portable puppet shows, the Gutter Puppets, that would talk about the Black Panther Party for Self Defense and its Ten Point Program.

Two days later, Martin Luther King was killed on a motel balcony in Memphis, Tennessee where he was to speak to the city’s striking black and white sanitation workers.

Two days after that, L’il Bobby Hutton was shot dead after he had surrendered following a shoot-out with the Oakland police department. Nevertheless, we persisted, and by June, the Gutter Puppets presented their first show featuring Big Black Panther and Li’l Black Panther in “You Got to Organize your Cave,” and “The Upstream Hog.”

A lifetime later, the murder of George Floyd loops back upon us through the testimony of witnesses. Nearly a year after his death, we must still cross and recross the boundaries set up by racism, to lean into its cold, careless wind.

A lifetime later, the murder of George Floyd loops back upon us through the testimony of witnesses. Nearly a year after his death, we must still cross and recross the boundaries set up by racism, to lean into its cold, careless wind.

Centuries old, these obstacles continue to roll across our landscape, beating against the consciousness we have desperately, eagerly accumulated. We are different. We are one. Change is possible. It’s time to listen, to learn, not as sympathetic observers, but as allies.

# # #

*Segments of this post are excerpted from a fictional work in progress. Although the scenarios are fact- and memory-based, please allow for poetic license. Tks! — cd

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

Thanks for sharing the stories–stark indeed. I remember some of those images too. Isn’t it something how past is indeed prologue. Things never resolved after the Panthers were persecuted, war faded, and neoliberalism bloomed–just festered for years. You had a chance to meet and work with some extraordinary people, and I trust in a whole new generation of committed people carrying things forward now.

Thanks for you response, Khati! I think you encapsulated that discouraging era perfectly. Forty-nine Panthers, executed in 1969 by COINTELPRO, the left coalitions devolved into nationalist and splintered extremes, and then the long, deadly Reagan era that — hopefully — we are just emerging from now.

I do have great hopes for the next wave of resistance and have a clear window on it through my teaching at Cal State LA. On hiatus now, but love those kids!

Charles, I was transfixed by this story and remember those times well. At Mills I was impressed, and frankly intimidated, by the occasional presence of Black Panthers on campus. I was especially moved by Bobby Seale’s description of “not enough” in your story. In the late 1980s I was taught by my mentors Dr. Deming and Dr. Gluckman about “artificial scarcity of resources,” a technique used in business to exert control over employees by forcing them to compete with each other for everything, leaving them too exhausted to question authority. It sounds eerily similar to what Bobby Seale was saying.

Thanks, Marian. I’m glad the story resonated for you. That ‘artificial scarcity of resources’ does sound diabolically universal and familiar, doesn’t it? So much of power wielded seems to be rooted in the control of others!

Charles, I have such a strong reaction to what you’ve written; so many ideas swirling so early this morning. First – your Featured image – so powerful! Then your discussion about beginning life in the projects of JP. My husband also began his life in the projects; on Egmont Street in Brookline, before the family moved to GI tract-housing in Framingham, then Wilmington (his father worked there), where they were the ONLY Jews in town. Eventually his mother cajoled his father to move to Newton, which they could barely afford, but she could be close to family and friends. And the kids could be with “their own kind” (my husband is the oldest of 5). My kids went to school with METCO kids, bussed in from Boston. One who went through school with my older son was the son of a Brandeis friend, who at the time had followed KC Jones as Brandeis’ basketball coach. Nkosi is now an artist and model; the family still lives in Dorchester and I remain in touch with the father.

I was truly struck by Bobby Seale’s words, their wisdom and plain-spoken sense. I loved your description of the call and response between Bobby and L’il Bobby, a vivid and appropriate way to describe their interaction. And then the tragedy that followed hard-upon your troupe’s meeting; first MLK’s murder, then Bobby Hutton’s. And yet your group continued on its path.

As you describe, we have looped back around to the heart-wrenching testimony in George Floyd’s murder case. I listen and also cry. When will justice be served?

Thanks for your kind and engaging words, Betsy. Interesting, the move to the country (pre-suburb, really) was based on a work plan of my father’s that fell through. Instead of returning to the city, we stayed on and, altho I don’t regret being raised a ‘country boy,’ I did become culture-starved until I could motor into Boston or bus to NYC.

The conversations with the two Bobbys are, of course, a mix of memory, archival reading, and some wonderful YouTube recordings of Bobby Seale speaking about those times. And we did continue with our Big Black Panther, Little Black Panther series as I described to John, below. Work for the future, Betsy!

This is a very powerful piece of writing. As long as people fear that helping other people diminishes what they will have for themselves and that “otherness” is somehow threatening to their place in this country, we will struggle for justice. Thank you for sharing this, Charles.

Thanks, Laurie. You sure reflected the core meaning of what I believe political power is all about. Probably always has been!

A really powerful story, Charles, and I feel especially grateful to have heard from someone who was so much closer to the Black Power Movement than I ever was. That said, I had actually heard of Bobby Hutton and knew that he was killed, but little more. And, of course, the death of George Floyd is so fresh in our minds, particularly as we watch his murderer’s trial.

I appreciate the optimism in your final paragraph. I want to believe it.

Thanks, John. Our interactions with the Panthers were fleeting but significant. And we did develop a series of puppet shows featuring two characters, Big Black Panther and Little Black Panther, based, of course, on the two Bobbys — Seale and Hutton. We performed them, guerrilla style in the parks using a small, quick-deploying puppet stage. We were often a big hit at People’s Park. One of my resistance novels begins with an unfortunate scene there, when our guerilla sortie encounters the Alameda County sheriff’s department who on that day — known as ‘Bloody Thursday’ — routed People’s Park demonstration with live ammunition.

I must admit, I am still learning to emphasize my optimism re: the future in the context of my great fears.

Thanx for always doing the good hard troubling work Charles.

Thanks, Dana. Sorry to cause so much trouble ;-)! Maybe it’s good trouble, at least some of the time.

Tis I’m sure!

Wow, Charlie, this is a remarkable story from beginning to end. I love your heroism on the school bus, making the driver go back and pick up the black student. Then studying the blues at a Quaker camp, followed by Harvard at a time of “gender apartheid” (great term!). But of course the piece de resistance is the meeting between the Black Panthers and the SF Mime Troupe. Thank you for reproducing that very powerful presentation by Bobby Seale and Bobby Hutton. It still rings true today. Can’t wait to read your work-in-progress when it is ready!

Thanks, Suzy! We know those times have resonance with today’s, right down to the portrait of George Floyd and Emory Douglas’ prolific work for the Panthers… and ALL the people! Happy to say that, like Bobby Seale, Emory is still alive!

Wonderful to be pulled into that scene with L’il Bobby and Bobby Seale. I saw Bobby Seale much later on, at the University of Illinois in the mid-1990s. He was still underlining that he always wanted to unite with whites to fight the system. In fact, he found it insulting when police accused him of being anti-white. (I thanked him for showing up. Jokingly, I told him the last time I came out for him, he didn’t show; it was in New Haven CT, and he was in prison on a homicide charge at the time. He was able to laugh about it with me.)

Yeah, Dale, Bobby Seale is still out there talking the good talk. Wonderful to hear him talk. Check out you tube.