“What about Down Syndrome kids? They can’t even feed themselves. And I know, because I’ve got one in my own family—my cousin. She will have to be fed like a baby for the rest of her life.”

My own reconnecting with Laurel took place during the December holidays, spring breaks, or summers, the only times I was home from Harvard. I recall how special it was ...picking her up from the House family and bringing her home for the weekend.

I was an undergraduate, enrolled in a graduate course in Child Development at the Harvard School of Education. The quoted statement was from one of the grad students—whom I looked on as adults, since they were in their 20s and 30s. So far as I can recall, the professor did not repudiate or take issue with the comment. I was too shy, among these more mature and experienced students, to speak my mind. But the assertion made me furious.

My own sister Laurel had Down Syndrome. I knew that Laurel, age six at that time, was feeding herself and doing much more than that. But talking about Laurel, even to friends, was hard, because of my complicated connection to her. I wasn’t prepared to say anything at all in a graduate class.

I had only recently reclaimed any kind of relationship with Laurel. She was the fifth child in our family, all born of the same two parents, and arriving nearly 18 years after the first birth, that of my older brother Leon. Medical and spiritual advisors (that is, several doctors and one rabbi) strongly counseled our parents in 1965 not to bring Laurel home, not to welcome her into our family. That advice reflected the prevailing belief among educated people at the time. The consensus was that the intensive energy and labor that would be required by parents to attend to the needs of such a child would not be rewarded with any substantial developmental progress on the part of the child, and meanwhile, if there were siblings, they would be deprived of the attention and support they needed. Children born with Down Syndrome (the actual term used when Laurel was born was “Mongoloid;”) and many others with disabilities and chronic health conditions were clearly not recognized in the 1960s ethically, legally, educationally, or philosophically as the equals of their peers born with more typical health and developmental trajectories.

My parents accepted this consensus but could not stomach the recommended solution: placing Laurel in Indiana’s notorious residential institution for individuals of any age labeled “mentally retarded.” Here is a clip of a man speaking retrospectively about the terrible experience of institutionalization (from a different state). I am so grateful that my sister never had to experience this.

https://mn.gov/mnddc/parallels2/one/video/video76a-freedomworld.html

Mom and Dad prevailed upon the hospital to keep Laurel in the newborn nursery for some extra days beyond my mother’s discharge, while they devised an alternative plan. Contacting people they knew in the world of social welfare, they were able to get Laurel speedily approved to enter the state’s foster system, and she was assigned a foster home. My siblings and I saw her just once, through the window of the nursery, before she was taken to live with her foster family.

By the time I was taking that graduate class at Harvard, Laurel had lived with three foster families. After little contact with her in the earliest years, which covered the first two placements, my parents had begun to build a meaningful relationship with her during the third placement. The foster mom was a loving woman named Vera House. She and her husband Bob had previously raised children of their own, but Laurel was the sole minor in their household at this time. They had moved to Indiana from Kentucky, like a lot of other white migrants seeking blue-collar jobs. They lived in a very modest house on a crowded city street, in contrast to our more spacious ranch home with a front- and backyard outside the Indianapolis city limits. I believe Vera and Bob were a bit older than my parents; likely in their early 50s when Laurel was young.

Laurel was not yet two when I left home for college, and I don’t believe I had seen her at all since that one painful glimpse in the nursery. It was after Leon and I were gone that my parents began to arrange for Laurel to spend time at our home, eventually including overnights by the time she was three or four. Some time after Laurel turned four, Mommy House (as Laurel called her) was hospitalized due to Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, and Laurel came to stay at our home for several weeks.

My own reconnecting with Laurel took place during the December holidays, spring breaks, or summers, the only times I was home from Harvard. I recall how special it was when I got to be the driver once, picking her up from the House family and bringing her home for the weekend. She was on a regular schedule by that time, living in two households, like a child in joint custody following a divorce. She was happy and spirited, very comfortable with her two-family existence. She was able to articulate in one long sentence during our ride that she went to “Mommy House Monday Friday” and “Mommy Fink Friday Sunday.”

My parents had realized after Vera’s hospitalization that they were ready to bring Laurel home full-time, but they respected and appreciated all that Vera had done. They knew how attached she was to Laurel (and Laurel to her) and were not in any rush to end an arrangement that had Laurel on track to be a happy kid and one who was making developmental progress beyond what anyone had dreamed at the time of her birth.

The year I was enrolled in that grad class, the cancer cut short Mommy House’s life. There was no thought of any option but to have Laurel move back into the family home for good—and that is what happened. It was not only Laurel, however, who mourned the loss of Mommy House. Mom had grown very close to Vera. They had developed a habit of speaking on the phone almost daily, which began with updating each other on every aspect of Laurel’s skills in self-care, her vocabulary, and her management of social interactions. Over the years, it had evolved into a friendship where many long conversations had nothing to do with Laurel. They became one another’s confidantes on many aspects of each other’s lives. It was an unlikely but beautiful bonding of two women from widely divergent educational, religious, and cultural backgrounds.

As my parents and then we siblings got to know Laurel, and as she made the transition back into our home, the concept of equality as a living, breathing commitment arrived in our lives as well. In 1965, none of us were encouraged or even permitted by the larger society to view people with her diagnosed condition as our true equals. Not equal to the rest of us in dignity. Not equal in respect. Not equal in having aspirations for a life full of opportunities and possibilities for education, work, leisure, social relationships, and more. But a few years later, it is fair to say our perspectives were very different. Mom and Dad truly embraced her as a daughter who was entitled to and would receive the same parental devotion as the rest of us. We siblings would learn to take an interest in her and develop a loyalty to her that would be akin to our interest in and our loyalty to one another.

How did that happen?

First, I have to pay homage to the parents, unheralded and nameless, who laid the groundwork before Laurel was even born. They asked questions about the lack of respect for the basic needs of children with disabilities and began forming grass-roots networks which grew into organizations such as the Association for Retarded Citizens (now known simply as the ARC), United Cerebral Palsy Association (now known only by its acronym, UCP, because it serves individual with many types of disabilities), and the Down Syndrome Congress. Here is a short video clip from a meeting of such parents from the 1950s.

https://mn.gov/mnddc/parallels/five/5a/parents-organizing.html

By the late 1960s, persons with disabilities themselves began organizing and becoming active in raising their own voices. The voices of those with Down Syndrome and other cognitive disabilities did not become a substantial part of this chorus until the 1990s; the first to speak out were those with physical impairments from polio and from accidental (or war-related) injuries. Here is Ed Roberts, who helped found the Independent Living movement, which started in Berkeley, CA, and spread nationwide. Some people have called Roberts the Martin Luther King of the disability rights movement.

https://mn.gov/mnddc/parallels/six/6b/ed-roberts-changing-attitudes.html

The efforts of family members and of individuals with disabilities were having some effect in shifting the way our whole society thought about persons with disabilities. But this kind of change does not happen in one fell swoop; it happens, especially in its early years, one person-at-a-time. In a very real sense, I believe it was Mommy House who brought the concept of equality to our family. In Vera’s home, Laurel received the same dignity, respect, and attention as any other person. She supported Laurel in mastering many skills that were not common among young children with Down Syndrome at that time. I remember my mother telling me that Vera had one important rule from the time Laurel began to speak: The expression “I can’t” was not allowed.

Under Vera’s tutelage, Laurel learned to use her utensils to eat properly, to drink properly, to use her words to ask for second-helpings or to say when she was ready to leave the table, to wash her hands before and after meals, to master toileting., to learn to get dressed and undressed. By observation and assimilation, my parents—and to some extent the rest of us in the family—followed the lead of Mommy House. We tried not to lower our expectations and do things for her just because she had a condition that slowed her cognitive progress compared to the rest of us.

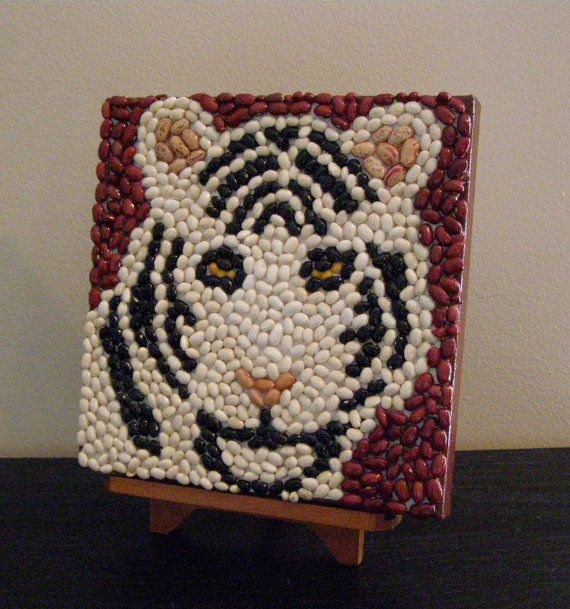

A year or two after Laurel came home, I was working in a childcare center in the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston. I brought home with me the materials for an activity we had introduced to the preschoolers with whom I worked—making mosaics on cardboard backing of a tiger with a jungle background. The yellow-orange tiger’s body consisted of popcorn, with black beans for the stripes and red kidney beans for the eyes. The jungle background was made of split peas. Laurel got very involved in making this “project” over the course of several days. We had finished the tiger but had not quite filled in the entire jungle. Then I returned to Boston.

Next time I visited Indianapolis, several months had passed. One of my parents met me at the airport and drove me home. Before I could even grab my suitcase and get out of the car, Laurel came running out (prompted by nobody to do so), with something in her hands. “Dale, I still have our project! Here it is! We have to finish it!” There was the tiger on its backing, still intact. I had forgotten that we had left part of the jungle incomplete, but she remembered. She was eager for her big brother to help her finish it. My smiling sister viewed herself as a full-fledged and equal member of the family, and I viewed her the same way.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Lovely, personal story of inclusion and equality, Dale. Thank you for sharing this intimate story. If one thinks about it, I believe the Kennedy/Shriver family worked hard at inclusion with their focus on the Special Olympics. Eunice was very moved by her sister Rosemary, who was only a little out of step in the late 1930s until her father tried that “new” treatment: the lobotomy, which left her helpless for the rest of her life. Her siblings took her cause as their own and worked tirelessly for the cause of those with mental and physical handicaps.

I did not know that Rosemary’s difficulties were affected by a lobotomy. But I agree that the Kennedy family played a truly pivotal role. As one example, every state has a federally funded research center on Developmental Disabilities (I worked at the one in CT for a number of years) ever since the days of the JFK Presidency. (They started out as research on “MR” but now function broadly related to inclusion of people with all forms of disability.) Also many people don’t realize that a big portion of Special Olympics is now devoted to “Unified Sports,” where athletes without disabilities are mixed in 50/50 on teams such as volleyball, baseball, and basketball with athletes who have cognitive or developmental issues. So they have evolved with the changing values.

A powerful story, skillfully told, Dale. I didn’t realize the change in the Special Olympics. In 1995 the organization held its Olympics in New Haven, and the company that employed me was a sponsor. We were encouraged to help out and my partner and I did over several days. A marvelous experience.

Wow. What a story. Thank you for sharing this profoundly moving and informative account.

What a lovely, touching story, Dale. I think it reflects not only your family coming together wonderfully around Laurel but also all of our greater understanding and acceptance of Down Syndrome and the people who have it.

And your story is also an important reminder that this prompt about inequality is not limited to just issues of race or gender. Thank you for that as well.

Thanks for sharing such a personal story, Dale. I appreciate getting to know Vera, your mother, and Laurel…and you on a deeper level. I could almost hear Laurel’s voice and feel her excitement when she ran out to greet you with project in hand. And though you don’t mention your feelings, they come through loud and clear. Beautifully written.

Dale, as the grandparent of twins with disabilities, your story meant so much to me. People with disabilities face discrimination throughout life and the burden of low expectations, especially in school. Their families have fought inequality in so many ways. Watching the clips you included reminded me that we have come a long way. Sadly, I think we still have a long journey to arrive at a place of equity, fairness, acceptance, and appreciation of people with disabilities.

Yes, we have still a long way to go. But decision makers in government business and education at least know (most of the time) that they have to keep in mind that a good chunk of any population either moves around differently, communicates differently, takes in information differently, expresses themselves differently, and so forth, and they cannot simply be ignored.

What a lovely, touching recounting, Dale. I’m so glad that Laurel had caring parents and relatives like you to teach her and appreciate your gifts. I didn’t know of many organizations in the links, but I do remember Ed Roberts, who was famous around Cal. We have come very far in medical management of people with CF and Down syndrome (I just read that life expectancy has taken a great leap). Let’s hope everyone makes as much progress with educational and social needs.

As soon as the society stopped putting people in institutions, ,the life expectancy rose very dramatically, within a short period of years. There is no more than a marginal difference any more between a person in the USA born with or without Down Syndrome. Stigmatization and institionalization are killers!

As for thanking people like my family: we were lost so long as we followed the accepted thinking of those with high credentials in educated circles. We did better for Laurel when we followed the thinking of someone with a high school education at best. And I think that is not anomalous; it is typical of how people with disabilities have made progress. Just think how backward the attitude toward people on the autism spectrum would be if we left it up to the doctors, psychiatrists, etc. It was the parents and the self-advocates (people who have the condition and use their own voice) who have shown the way.

Thank you for writing this essay. One summer during my college years, I worked at an Easter Seal camp. I learned that many of the stereotypes were not true, and I probably learned more in those twelve weeks than most years in school.