My old man made a great teacher. He knew everything for the longest time. When I wanted to learn how to drive, he took me out into the field next to the barn that served as a dormitory for Friendly Crossways, a youth hostel sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee. We lived there for a while.

I had to hold onto the steering wheel to reach the pedals.

Before I learned to operate a car, my old man sat me down one night and taught me the design, elements, mechanics, systems and processes of the internal combustion engine, from crankshaft to carburetor. I was eleven years old.

The field was actually the farmyard of a New England dairy that had been converted to the hostel. Every summer day, a group of sunburned cyclers would arrive at the barn and fall exhausted under the elms that shaded the green, sloping yard. Elms. Can you imagine? Great, graceful creatures that had survived the blight of Dutch elm disease that had plagued New England since the 1920s, when the infection came across the Atlantic in a shipment of logs destined for the veneer industry in the mills of upstate New York.

But on the night my father taught me about the internal combustion engine, the exhausted bikers had eaten a huge meal of Swedish meatballs and potatoes and fresh corn and green beans, served up by Winnie and Barry, the two portly, generous Quakers who ran the joint. The revived travelers could be heard singing in the barn.

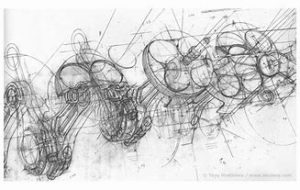

“We’ll start with the combustion chamber,” he said, “because that’s where everything begins. With the rapid expansion of gases.” Sketching as he talked, he described how the pistons are driven up and down in synchronized order as they rise to top dead center where the spark plug is timed to fire just before the piston reaches the top of its oscillation and begins its descent, driven to full expansion by the ignited vaporized gasoline.

“We’ll start with the combustion chamber,” he said, “because that’s where everything begins. With the rapid expansion of gases.” Sketching as he talked, he described how the pistons are driven up and down in synchronized order as they rise to top dead center where the spark plug is timed to fire just before the piston reaches the top of its oscillation and begins its descent, driven to full expansion by the ignited vaporized gasoline.

His voice was quiet, soft, and quick as he sketched the connecting rods arranged in offset sequence on the crankshaft. “And here,” he said, “straight line motion — the pistons driven up and down — is turned into circular motion that is, in turn connected to the clutch (you’ll need to know about the clutch) and the transmission and driveshaft. More on those later.”

I sat next to him, shoulder-to-shoulder; his pencil became an extension of his voice. “But back to the combustion chamber …” I soaked it up the way kids do when their brains are soft and supple and curious. By the time the night was done, I had learned all the basics of the way an automobile drove down the road.

The next morning, Saturday, we ate breakfast with everybody the way we did every Saturday morning while we stayed through a winter and summer at Friendly Crossways. My mother and father, my sister, Winnie and Barry cooking and gossiping and serving as one two-mouthed, four-armed, four-legged creature, joined at the crossroads of their lives in a sauce of sweet-natured harmony and discordant mutual annoyance, all packed into one chubby Quaker couple.

My father drove us into the field between the gateposts that punctuated a crumbling Yankee stone wall. The farm had ceased to function long ago, but the Barretts rented out the pastures to hay and graze other farmer’s cows. The field had been hayed once that summer and a lithe second growth gleamed yellow-green in the morning sun.

My father stopped the car, a Henry J, the brainchild of Henry J. Kaiser, the WWII industrialist whose shipyards manufactured the Liberty and Victory ships that carried the troops, supplies, and weaponry across both oceans to both wars.

My old man and I traded places. I had to hold onto the steering wheel to reach the pedals. My old man propped a fruit crate behind my back and the wild rodeo began.

“Okay, now this one’s the brake and this one’s the clutch. The one you have to reach for, that’s the gas.” He held me in his left arm and braced himself against the dashboard with his right. He was ready. He guided my right arm through the shift positions, first, second, third, with neutral in between and reverse way off in some weird position. I followed the shaft gate, silent, my mouth dry. My heart pounded.

I had pestered by old man to teach me to drive for over a month. I had discovered cars at the same time I had discovered girls — in sixth grade. It might seem an odd juxtaposition but my cultural instincts must have been hormone-sensitized. Girls and sex and cars had merged in the rambunctious, post-WWII American mythology and I had apparently been sucked along by the current.

I insisted. I wanted to drive. I didn’t care. My friend Roger lived on a farm and he drove tractors and everything. My old man never resisted. I think he was delighted that I was interested in one of the entry ports to his own world of science and engineering. I had spent most of my eleventh year listening to the Top 40 and desperately trying to train my hair.

“Okay,” my old man said. “Push down on the clutch.”

I stretched my leg and pushed the clutch with my left foot. It felt stiff.

“Harder!”

I pushed harder.

“Farther!”

I pushed deeper.

“Press it up and down. Get the feel of it. When you engage it, you put pressure on the spinning plate on the engine side. It rubs the spinning plate on the transmission side, the two plates grab each other, the gears in the transmission begin to turn the driveshaft and the driveshaft turns more gears in the differential to make the spinning take a right or left turn, depending on which wheel bears the most weight at the time, and…” He wrestled with my neck. “You begin to move.”

“Press it up and down. Get the feel of it. When you engage it, you put pressure on the spinning plate on the engine side. It rubs the spinning plate on the transmission side, the two plates grab each other, the gears in the transmission begin to turn the driveshaft and the driveshaft turns more gears in the differential to make the spinning take a right or left turn, depending on which wheel bears the most weight at the time, and…” He wrestled with my neck. “You begin to move.”

“Yeah!” I knew that. We had finished our lesson the night before with more sketches of the transmission and drive train. I never even stopped to question how I had absorbed so much but now, I could picture every moving part he described, high on his words and sketches. I was very excited!

He slid the gearshift into neutral. “Now turn the key,” he said. “Then press the gas.”

I did. The engine caught and roared, revving high.

“Enough, enough,” he said, “let the throttle…”

“The what?” Engine still roaring.

“The gas, leggo of the gas,” he said, laughing.

I took my foot of the pedal, the engine dropped to an idle. “Hey!” I said, and revved the throttle a few times.

“Don’t over-rev it, you’ll float the valves,” he said.

“Huh?”

“We’ll get to that later.” He shifted into ready-for-action mode, right hand on the dashboard.

“So now,” he said, “push in the clutch…”

I pushed in the clutch.

“Shift UP into first”

I pulled the lever up.

“Okay, now let the clutch out a little. Just a lit…”

I dumped the clutch and the Henry J stalled.

“Okay, too fast. The clutch plate has to slide against the transmission plate smooooooth.” He made a circular motion with his hands, then resumed the protective cover of his arm around my shoulder. “Are you in neutral?”

“Okay, too fast. The clutch plate has to slide against the transmission plate smooooooth.” He made a circular motion with his hands, then resumed the protective cover of his arm around my shoulder. “Are you in neutral?”

I took a deep breath and pulled down the gear shift. “Neutral,” I said.

“Okay,” he said. “You know what to do.”

I started the engine, revved it once…

“Naah!”

… and let it slow.

Push in the clutch.

I pushed in the clutch.

“Push the gear lever UP into first.”

I pushed up the lever. A terrible grinding sound began.

“Arggggh. Push the clutch deeper!”

I pushed and the lever slid into gear.

“No grinding,” I grinned.

“Grinding no good,” he said. “Now goose it just a little…”

“Huh?”

“Give it a little gas,” he said. “Just a little.” He laughed again. “Let’s go.”

I revved the gas a little.

“Let out the cluuutch. Slow. Smooooth.”

It was all I could do to let the clutch out slowly, the springy pressure pushing against my leg. The car began to move forward. Wow! I had the steering wheel in my hand, the engine revved and the Henry J began to swish through the tender grass. I was moving! I was driving! I looked through the windshield at the open field ahead. The car began to buck.

“Whoa!” My old man said.

When the car slowed, my foot would hit the gas pedal.The car leapt forward, my foot pulled away, the car slowed, my foot hit the gas, back and forth, back and forth.

“Whoa, buddy!” My old man was laughing. “Whoooa.”

“I can’t stop it!”

He pulled my body up under my arms. I still weighed less than one hundred pounds at eleven.

The car slowed and gently rolled into a stone wall, the engine stalled. In the silence, a single stone, placed there ages ago by some long-gone farmer, tumbled off the wall.

My old man put his arm around me. “Okay, Charlie,” he said. “You just learned how to drive.”

# # #

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

Wow, what a wild ride for an eleven-year-old! I love it that your father wanted to teach you all the details about how an engine worked before he taught you to drive. That was a terrific two-day driver’s ed course: classroom on Friday night, behind-the-wheel on Saturday morning. No doubt you’ve been driving ever since. And what an amazing looking car that Henry J is. Great story, Charlie, thanks for sharing it with us!

Yes, it was a crazy time to learn, but in the country, lots of kids (the boys only, of course, ca mid-fifties) learned how to drive on the farm. I did spend a fair amount of time after that, pre-license, roaring around farms with my friends. The stone walls kept popping up and hitting us, though. Very annoying!

Fantastic, Charlie! You just taught all of us how to drive a manual transmission. Wish I still had a soft and supple brain. Love that your father taught you all about internal combustion and how the engine and gears worked before you set foot in the car and you were just ELEVEN for Pete’s sake. And yes, I agree that driving, sex and hormones are all linked in the culture (anyone besides me ever have sex in a car?). We gained our independence by having wheels and, particularly growing up in Detroit and the ‘burbs, going “Woodwarding” (cruising along M-1, a major, straight road, rather like in “American Graffiti”) was a major pass time. Ah, the glories of driving.

Learning to drive with my father became one of those signature moments that we recall with great clarity. I wish I had those drawings he made so long ago, but I can still see them clearly. And yes, I did have a fair number of intimate moments parked beside those ever-present New England stone walls. Driving, especially on long road trips, has become a meditation for me and — for a short time — a lifestyle. Gypsy truckers, we were. Way back then, I also became obsessed with 1950s hot rods and European sports cars. You may recall my stories here regarding my long love affair with the internal combustion engine. “Serafina” and “The Lotus and the Schoolboy.”

I love your vivid description throughout this story. The details are wonderful and your father was so patient and wise. Having learned to drive on a manual transmission car, I loved revisiting how that all worked. Plus I learned a bit about the mechanics. Very interesting.

Thanks, Laurie! I’m happy you enjoyed this driving tale. My declassé obsession with cars grew in the hothouse environment of farm country. Later, when I was living on rural collectives in California and Colorado, my mechanical knowledge kept me out of trouble on plenty of occasions. You might enjoy perusing two other Retro stories I wrote about my car-crazy days. “Serafina” and “The Lotus and the Schoolboy.”

Charles, this is the ultimate learning to drive a manual transmission story. Your father sounds wonderful.

Hi, Marian. Yeah, I was aware that I was close to writing an instruction manual. But the experience has remained so clear in my recollections. I wish I had kept those engine drawings my old man sketched! I recall them just as clearly but drawings fell victim to my feckless gypsy ways. Cars remained an obsession well into adulthood!