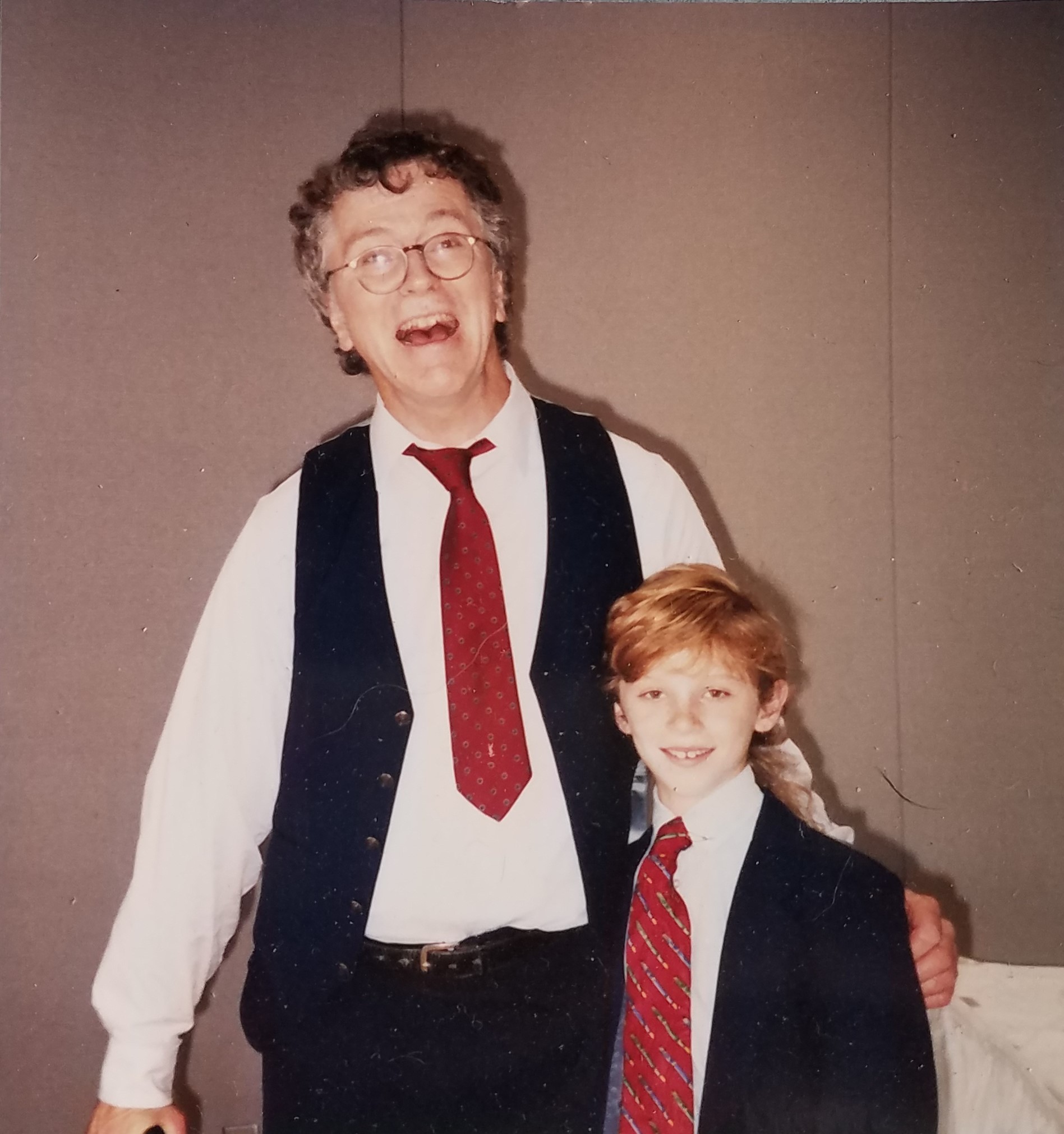

Barry with Ben at Sabrina’s bat mitzvah, 1997 – already pretty shaky at that point

When my grandfather died, I was not allowed to go to the funeral. It was 1962, I was eleven years old, and he had been the most important person in my life. In those days it was not considered appropriate for children to go to funerals. I think it would have helped me process his death if I could have gone. See my earlier story, No Way To Say Goodbye, for more details.

As an adult, I have given public final farewells for three important people in my life: my father, my mother, and my ex-husband.

As an adult, I have had the occasion to give public final farewells for three important people in my life: my father, my mother, and my ex-husband.

When my father died in May 1995 in Florida, at age 85, my New York sister flew down to be with my mother, for emotional support and to help her with all the details that needed to be taken care of, but the family didn’t assemble. I had actually been there three weeks earlier with my husband and children. My mother had told us we had better come for spring break because he probably wouldn’t still be alive by summer, and of course she was right. In August, when the whole extended family gathered for our annual family reunion, we held a memorial service at my sister’s synagogue in Brooklyn, with a reception afterwards at her house. I wrote my remarks on a napkin on the airplane as we were flying cross-country. Afterwards my mother asked me if I could type them up for her, but I don’t think I ever did.

When my mother died in February 2017, also in Florida, at age 95, my two sisters were there with her but I was not. I had been with her for the full week before that, and then had gone home, planning to come back again in a couple of weeks, but she didn’t last that long. When my sisters called to say she had taken a sudden turn for the worse, I asked if I should come back. They said I could if it would be meaningful to me, but she was already at the point where she wouldn’t know whether I was there or not. So I didn’t. Each of us ended up holding some kind of service in our own cities. Mine was a shloshim service, held thirty days after her death, at my house in Sacramento, with my rabbi and cantor officiating, and a few dozen friends in attendance. My remarks, beyond thanking everyone for coming, consisted primarily of reading a Retrospect story I had written about her.

Almost halfway between the deaths of my two parents was the death of my ex-husband Barry in June 2003. In his case, even though I wasn’t married to him any more, I was the only responsible adult around. It fell to me to identify the body, write the obituary notice for our local paper, and plan the funeral. The funeral was held a week after his death, in the chapel of the cemetery where his father was buried and he was also going to be buried. The casket was present (but not an open casket, I’ve seen a few of those and found them horrifying), and there was a procession out to the gravesite after the service, where we watched the coffin being lowered into the ground, and threw handfuls of dirt on top of it, according to the Jewish custom. I wrote about his death and telling the children he had died in No Way to Say Goodbye, part two.

Here is my description of the service in my earlier story, in case you don’t want to read the whole story:

It was a beautiful service. I spoke, Barry’s brother spoke, and even Sabrina decided to speak. Many of Barry’s friends and colleagues were there, and shared their memories of him. They generally directed their comments to the kids: “Sabrina and Ben, you probably didn’t know this about your father . . . .” The memories everyone shared, as well as the songs and prayers, and the ancient ritual of Kaddish, were really good for them, and helped immensely with the healing process.

And here is my eulogy, which I amazingly just found in an old computer file. Explanatory notes are in brackets and italics. Don’t feel obliged to read the whole thing, I included it here in case my children ever want to know what I said at their father’s funeral. Read the first paragraph, but then you can skip down to the end if you like.

- * * *

It’s really amazing to be standing here and looking out at all of you dear friends. I am so touched and honored that you came here for Barry. I have talked to a number of you over the past week, and we have shared some wonderful memories. If I had even had an inkling, 6 months or a year ago, that he was this close to the end, I would have called you all then, and we could have had a gathering like this when he could have enjoyed it. Barry was always one to appreciate a good party, and I know he is glad we are all here today because of him, but I wish he could be here to see you all too. I hope that many of you will come up here and share a memory or two with all of us.

[What I really wanted to say was: “I’m so mad at you for turning up now to say how much you loved him, when it’s too late for him to hear you. Where were you when he needed you for support? He called many of you asking you to take him home, or help him function, when the Parkinson’s made him frozen, and you were always too busy. Even just to come over and hang out with him when he was alone would have been great, but you never had time for that.” I knew I couldn’t say those things, so I settled on the sentence about how I should have called them 6 months or a year ago. I don’t know if anyone got the unstated message or not.]

Barry and I had 2 different stories about how we met – – I said we met in a bar, and he said we met in church, and both were true. Our first meeting was in the bar at Harlow’s, on J Street, an “accidental” meeting arranged by our mutual friend Janet Robinson, who thought we had a lot in common and should get together. Our second meeting was a week or so later at a church, where we were both attending the first rehearsal of the season for the Sacramento Symphony Chorus, which we had coincidentally both just joined. We were two lawyers who had more of a passion for singing than for law, we were both tall, into suntanning and drove little European convertible sportscars. What more could one ask for?

Barry and I were together for only a decade, from 1980 to 1990, but it was a very significant decade for us. We were together when we heard the news that John Lennon had been shot, and we worked together to get John van de Kamp elected Attorney General. We watched with dismay as Governor Jerry Brown was replaced by George Deukmejian, and Barry left his beloved Office of Planning and Research [a high-level state think tank] for the Sacramento County Counsel’s Office. During much of that decade, he played saxophone and sang in a rock and roll band called the Chain Gang, later called Chain Reaction, and sometimes they even let me sing backup vocals. We had a wonderful wedding in Old Sacramento, which many of you attended, and we went to Kenya on safari for our honeymoon. Then, came the most important events of our decade, the birth of our two children, Sabrina and Benjamin. They are both here with me today, and most of you probably remember them as babies. But if you haven’t had a chance to meet or talk with them in a while, I urge you to do so, because they are remarkable people. Sabrina will be going to Wells College in upstate New York in the fall, and Ben will be a sophomore at McClatchy High School, where he plays trombone in the band. Barry was very proud of them, as am I.

That decade also brought the first diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. It was in 1984, when I was pregnant with Sabrina, that we first went to Columbia University Hospital in New York for a consultation. At that time, he had noticed a small amount of shaking in his hands, mainly when he was holding his music folder to sing in the Symphony Chorus. The doctors said that it might be Parkinson’s, but it might not, and to keep seeing his doctor at home and come back in a couple of years. So we went back in 1986, and the doctors still weren’t sure, but they said here is some medicine for Parkinson’s – – if it helps decrease your shaking, that means you have Parkinson’s, if it doesn’t then we will have to look for something else. The good news was that the shaking stopped when he took the medicine. The bad news was that he did indeed have Parkinson’s.

He didn’t want anyone to know he had Parkinson’s, and I was not allowed to talk about it. But gradually the symptoms increased, and after a while you all knew something was wrong, even if you didn’t know what it was. Eventually though, people began asking directly, and he had to admit to himself and to you that he really did have Parkinson’s.

There was so much work being done on Parkinson’s that he was sure that he would be cured. Three years ago he had surgery in which pacemakers were inserted in his chest to stimulate his brain, and we all thought this would bring back the old Barry. Unfortunately, it didn’t seem to do much good. And in the last year, it was not only his body but his brain that was being affected by the disease. It was only in the last couple of weeks, though, that it became apparent that he was reaching the end of the line. Something happened in his brain, which the doctor compared to a stroke, although it wasn’t technically a stroke, and after that Barry was mentally gone. His body lasted a little longer, but he was refusing to eat, and so it seemed that he just didn’t want to keep fighting any more. A feeding tube could have been inserted to keep him alive, but he had made it clear that he did not want that, and so we had to let him go. At the end, he just slipped away, last Friday night, while we were at Sabrina’s high school graduation.

[My notes say “not sure about this paragraph” so I don’t know if I delivered the following sentences or not.]

Those of you who may have been around him in the early 90s may have heard him say negative things about me, because our breakup was not easy and he was very angry for a while. But I want you to know that we did get along well in the later years, held together by a bond much stronger than marriage, our mutual love and concern for our children. I subsequently remarried, and Barry got along well with Ed. Indeed, Ed was often called upon to help Barry when he was physically stuck, and so they developed a certain closeness whether they wanted to or not. Barry was also very fond of Ed’s and my daughter Molly, who just turned 7, and is also here with us today.

Finally, I just want to thank you again for being here and telling your stories. It means a lot.

- * * *

Whenever I go to a funeral or memorial service — and there have been many in recent years — I have the same reaction listening to the eulogies that I had at Barry’s. It is such a shame that the person being discussed doesn’t get to hear what everyone is saying! If I end up with an illness where I know I am going to die, I want to assemble all my relatives and friends and have the equivalent of a memorial service while I am still alive. That way I can hear all the stories they are telling about me, and enjoy them along with everyone else.

Brava Suzy, the story of Barry’s funeral is both funny and very moving!

As for your wish to be at your own memorial service – when you hit 120 we’ll consider it!

I’ll hold you to that, Dana!

Your story about Barry is incredibly moving. In part, I say that because my father also died of Parkinson’s, albeit when he was 90 years old, so it was a very different, and less shocking, ending. But more because of both the moving words of your actual eulogy and your inclusion of what you were thinking if not saying. It reminds me of O’Neill’s “Strange Interlude,” which included just such “soliloquies” of the speaker’s actual thoughts. It is an incredibly effective technique, particularly in the context of a eulogy, where we are all schooled never to speak ill of the dead — or anyone else, for that matter.

And I fully agree with your last paragraph of wanting to hear one’s own eulogies. Of course, if I ever did with mine, I’d be inclined to think, “Well that’s all very nice, but what did you really think of me?”

Thanks so much for sharing this, Suzy.

Well, I guess I’ll have to read “Strange Interlude” now, since I never have, although I’ve read a lot of O’Neill plays. I need to find out whose technique I am using here. As to your comment about hearing your own eulogies, I’m sure nobody would have anything bad that they were really thinking about you!

Here’s the Wikipedia entry on “Strange Interlude,” including an explanation of the soliloquies: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strange_Interlude Interestingly, as I thought about it more, I realized that I had first learned about the play in Mad Magazine, where it did a “What they said” vs. “What they were thinking” satire of some sort.

And I plan not to ask anyone who thinks badly of me to give a eulogy at my funeral.

Lots of depth and complexity here, Suzy. You really stepped up in your helping Barry at the end, and with the eulogy. Echoing John, you are very forthcoming about what you thought but didn’t say directly. I applaud you.

Thanks, Marian. I appreciate the applause.

Suzy, the notion of being able to attend one’s own funeral and hear about how you touched people’s lives is a common fantasy. You were right to be thinking about how people come to funerals but not to visit when someone is very sick and craving company. That is so true. I hope you did read that paragraph about how he accepted Ed and Molly. That was truly a beautiful thing.

Thanks for your comment about that final paragraph of my eulogy. I wish I remembered whether I said it or not.

Suzy, this is a moving account of meaningful deaths in your family, but particularly that of your first husband’s, how you coped and helped his (your) two children cope with it and what words you chose to share at his funeral to help the children and others mourn.

Parkinson’s is a cruel disease. My Vineyard neighbor died from it. He had a much younger wife who cared for him to the end, even when his children couldn’t bear to see him. Knowing we would be kind, Mara had us over for dinner and we would jabber away, even though he couldn’t respond, which is just what she wanted.

Your idea of having a celebration before death so we can hear what people think of us is great. I second (or third) other’s favorable reactions.

Thanks, Betsy. Great that you spent time with your Vineyard neighbor (the judge, right?) when others couldn’t do it. It’s hard to get people to do that when the person is no longer his old, fun, healthy self.

Love the parentheticals here. Oh, what I wish I could say! As my sister was dying she was inundated with cards and letters from friends near and far, telling her how much they loved her and sharing some memories and photos. At one point, she said, “I guess I really am awesome!” And I responded by telling her that you can’t believe everything you read–cracking both of us up! Sisters–what can I say? Enjoyed reading these pieces, Suzy. You did right by your ex, for sure.

Thanks, Risa. It’s wonderful that people were writing to your sister to tell her how much they loved her, and sharing memories and photos. Of course you had to tease when she said she was awesome, but I’m so glad she got that message while she was still alive.

Oh, Suzy, to survive the loss of a loved one to that most horrible of afflictions! What strength that took! I was moved by the complexity of the cross-currents you described, so many elements when children are involved. For me, your italicized comments created such power and honesty. What if we all did that as part of the farewell ritual in some way that was accepted, not by softening the words, but by embracing those thoughts and feelings as part of our reality. A sad and moving piece, it is, one that creates a clear window into your strength and stability. Thank you!

Thanks for your comment, Charlie. It took more strength to deal with the last ten years of his life than it did to deal with his death. By the time he died it was kind of a relief.

I know how that feels. But the relief only comes after the conditional mix of love, anguish, and anger.

Oh, Suzy, what a powerful story with so many facets and dimensions and emotions. How terrible to lose oneself piece by piece and at a relatively young age. Our high school friend Sally (of those Woodstock photos) has had Parkinson’s for 20 years, and she struggles just to get through each day. The fact that we can just live normal ordinary lives has to be some kind of miracle. I’m glad you included the eulogy (and the commentary).

How terrible that you weren’t allowed to attend your grandfather’s funeral, especially when he was the most important person in your life. What were the adults thinking? I guess the mentality was to “spare” kids the sadness, and yet it deprived you of saying that final good-bye along with rest of your family. An eleven-year-old is not a child, and can certainly grieve just as deeply as adults, perhaps more, since they did not have as much time with the person they lost.

I think it would be interesting to hear what our friends would say about us after we pass. Many years ago, I had an acquaintance who’d had a child with a friend of hers. When he was given less than a year to live, they decided to get married for the sake of their child (now six years old) and also for inheritance purposes. Although the groom was losing weight quickly from cancer and looked frail, they planned a enormous wedding with hundreds of people. Before I could even ask why, she said that their friends would either attend the wedding or all come together for his funeral. It made sense to me, and the groom got to enjoy his final send-off.

As always, thank you, a moving and engaging story.

Joan, thank you for this beautiful comment! You really “got” every aspect of my story. And I love hearing about the enormous wedding held because the groom had only a short time to live, so that friends would come together for a wedding instead of a funeral. That’s perfect!