During the Vietnam War, I was one of the fortunate young men of draft age who saw through the lies and hypocrisy that surrounded the violence against a small, agrarian nation. Vietnam wanted— after centuries of occupation by the Chinese, the French, the Japanese, the French reprised, and the Americans — to determine its own destiny through democratic means.

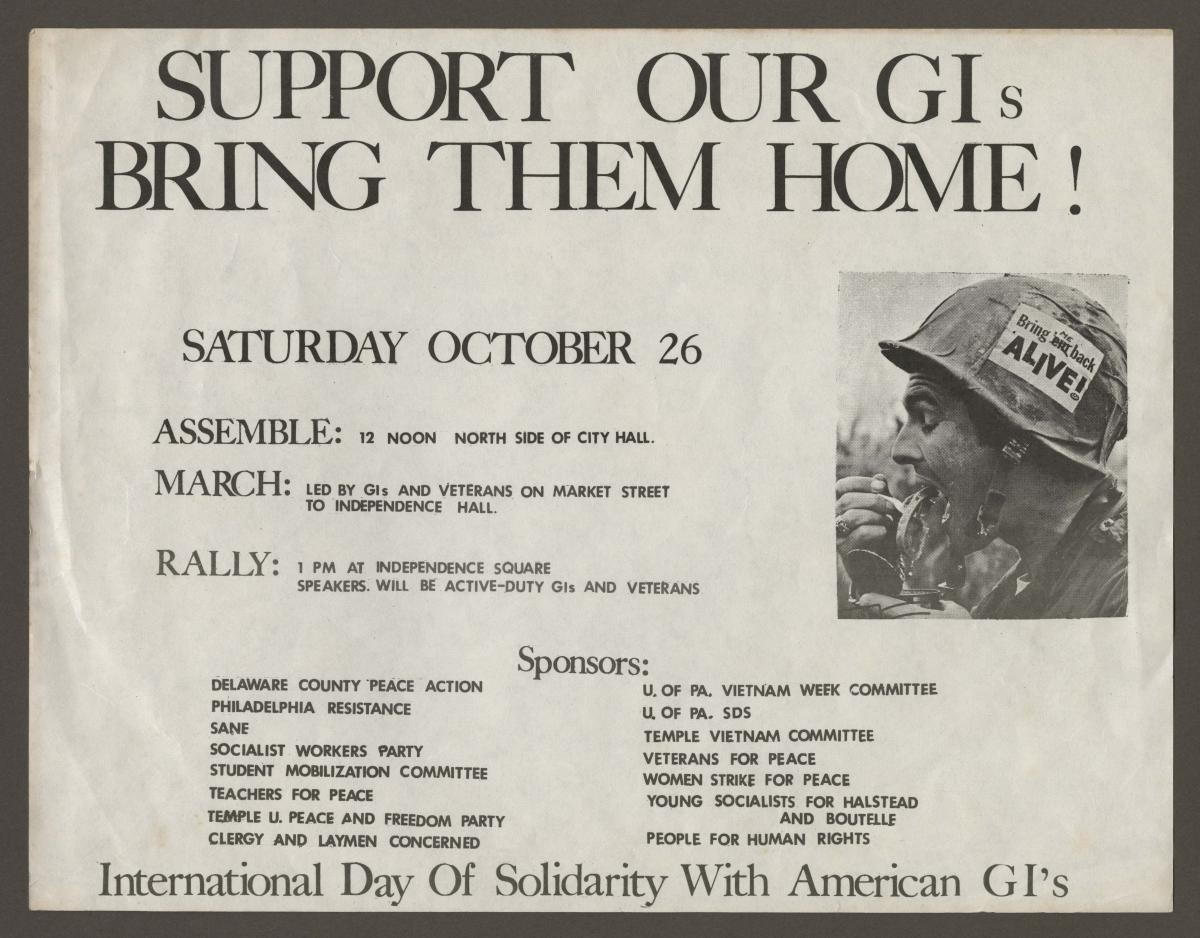

Support Our Troops / Bring Them Home

The Vietnamese, after so many battles for independence, called our twisted invasion simply “The American War.” Back home, many young men mistook the Vietnam war as a struggle similar to the “good war” our parents had fought against fascism in Europe, Africa, and the Pacific.

During the Vietnam war, all men between the ages of 18 and 26 were required to register with the Selective Service and were subject to recruitment into the U.S. army. Once drafted, we would be trained and stamped as G.I.s, short for “Government Issue.”

There were plenty of exceptions, but the draft hung over most males during the war years. As the war grew, anti-war protest grew. Many of us refused to go through the military induction process that stamped us as “Government Issue — GIs — as if we were pieces of meat, trained to kill.

As the war cycled through recruits and draftees, soldiers who had fought in Vietnam began to return home. Amidst the growing protests, war-weary soldiers often disembarked at American airports to be greeted by their friends, families and — so the myth goes — antiwar protesters who spat on the veterans and called them “baby killers.”

Bullshit.

The spitting myth flies in the face of the deep understanding that most of our generation shared — that a large percentage of returning veterans had been drafted into the war against their will, their beliefs, and their everyday lives.

Contrary to the implications of the spitting, baby-killer myth, support for the troops in Vietnam became a powerful position in the antiwar movement. “Support the troops Bring them home” became a familiar slogan, sign, and bumper sticker.

Contrary to the implications of the spitting, baby-killer myth, support for the troops in Vietnam became a powerful position in the antiwar movement. “Support the troops Bring them home” became a familiar slogan, sign, and bumper sticker.

One Vietnam vet, a sociology professor named Jerry Lembcke began to research the spit myth. As a returning vet, he had never experienced any negative sentiment from antiwar protestors and could find no credible instances of anti-war activists spitting on veterans. Instead, he found what we activists already knew, that a supportive, empathetic relationship grew quickly and deeply between veterans and anti-war forces. Together, protestors and vets exposed government and military leaders as the real villains, not the returning “grunts,” as Vietnam-era soldiers were called.

G.I. coffee houses sprung up outside military bases, refuges where soldiers could relax, meet antiwar activists and returned veterans, leaf through the proliferation of underground newspapers, and just hang out.

In 1971, while the war was in full swing, hundreds of Vietnam veterans gathered outside Nixon’s White House, and threw their medals over the walls and gates that had been erected to protect the war’s perpetrators from angry protesters. These vets did not want to be rewarded for what they had done in Vietnam.

In 1971, while the war was in full swing, hundreds of Vietnam veterans gathered outside Nixon’s White House, and threw their medals over the walls and gates that had been erected to protect the war’s perpetrators from angry protesters. These vets did not want to be rewarded for what they had done in Vietnam.

In 1998, Lembke published The Spitting Image, where he reported his findings. The Spitting Image also describes the Nixon administration’s perpetration of the spitting myth as a tool to drive a wedge between military service members and the anti-war movement by portraying democratic dissent as a betrayal of the troops.

So, let’s not simply celebrate the “service” of the U.S. military as a force for extending American policy abroad, to increase our “national security” — whatever that is. A military presence anywhere can protect and serve or create horrendous violence and injustice. And in the spirit of Veterans Day, let’s respect the reality that military action and service can wreak terrible damage on the men and women who enforce our presence in the world.

# # #

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

Thanx Chas for your compelling story, as always I learned much I hadn’t contemplated before.

During Vietnam our friend Ron was a conscientious objector, other friends served, and others did all they could to avoid conscription. We respected them all.

Thanks, Dana. Vets and peaceniks did merge. It was an important and fruitful partnership thru the war, the protests, and the aftermath.

I turned eighteen in 1974, so the war and the draft wound down just in time for me. But I had several years before that when it seemed like the insane meat grinder would go on forever. I gave much thought to finding a way to stay the hell out of it. Even my pretty conservative, WW-II, Purple-hearted-receiving vet father knew that the war was a scam and was completely behind me staying out. Jail was not an option. I didn’t want to go into exile in Canada not knowing f I could ever come home. My plan was to join the Navy; if you weren’t a pilot, the odds of getting killed by the VC or a SAM were pretty slim.

But I knew even then that the spitting and “baby killer” bullshit was just that.

Love the “insane meat grinder” description. Interesting to know that your father’s WWII experience did not blind him to the Vietnam fiasco. Your contemplation of alternatives sounds very, very familiar. So many similar conversations everywhere, back in them days.

Thank you for enlightening us and dispelling the myth of the spit-upon returning vet. I just finished reading Heather Cox Richardson’s interesting book, which takes us back to Nixon’s time (among other moments) and reveals many times he lied (including deliberately NOT ending the much hated Vietnam War so he wouldn’t lose the election; a fact recently revealed). So this new piece of data does not surprise me. And of course, most people who serve in a war (including WWII, however justified that was) come back with some form of PTSD, though it wasn’t called that back then.

Thanks for reading, Betsy. It’s been a thorny issue for me. The disparity between the New Left activists and hippies created yet another gap, along with Leary’s obnoxious “turn on,tune in, drop out” also offering a do-nothing recipe in the counterculture. The yellow ribbon movement also served, during the Iraq fiasco, to create a rift between activists’ support of troops and the general public confusion. t does go on…

Thanks, Betsy. I thought Lembke’s analysis of the Nixon use of the spitting myth to drive a wedge between military people and the anti-war movement by portraying democratic dissent as a betrayal of the troops was infuriating. And then there was that nauseating “tie a yellow ribbon” was deja vu all over again for Desert Storm, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Ugh.

I remember the rage — one of many waves — at realizing (in real time) that one of Nixon’s many motives for continuing the war involved his suck-ass re-election. Gawd, woman, will it ever stop???

Thanks for bringing to readers’ attention that book that very carefully searched out evidence about the “spitting on soldiers.” (And found none.).

Like you, I observed only respect and solidarity among the radical factions of the antiwar movement and the military ranks. (As for colonels and generals, that’s a different story.).

There were some “peace activists” of a more moderate/liberal bent who did try to heap guilt on the shoulders of the rank-and-file GI as well as the rank-and-file workers in defense plants. But even in so doing, they did not engage in spitting–only in misdirected (in my opinion) guilt-tripping.

For the benefit of our vast pool of readers, I will mention the movie FTA, produced by Jane Fonda, the title translates either as Free the Army or F—- the Army. It had a lot of great documentation of those coffee houses outside Army bases during the war. In fact, now that I’m thinking of it, I would enjoy watching it again if it’s streaming somewhere,

Wow! I knew the FTA people well. After the split in NYC, many of the Newsreel people came west and worked out of the SF Mime Troupe studios. I would love to see it again too.

P.S. It appears that a restored version of the movie FTA is available on Netflix and I will be watching it soon.

Great, Dale! I look forward to it. Have several friends in cast who migrated to SFMime Troupe. Good flick, for its time and often after. Thanks!

Thanks for bringing those memories back so clearly, and especially for the debunking of the spitting story. Talking about the draft reminded me of the scene in “across the universe” when Max gets drafted to the tune of “she’s so heavy”—if you haven’t seen it you might like it.

Thanks, Khati. I know Julie Taymor’s work well from her theater beginnings. She worked with Peter Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theater for years and LOVED “Across the Universe.” Much of its conception carries noticeable derivations from Bread and Puppet if you know their work. We in the SF Mime Troupe often broke bread with Bread and Puppet and in 1968, we hosted a radical theater festival with them and Luis Valdez’ Teatro Campesino.

Great memories of wonderful theatre groups you have! I wasn’t familiar with Bread and Puppet, but do know the Teatro Campesino through association with the UFW. All brilliant and good stuff. I have to assume there are current groups also embodying the anguish of our present time with love and humor, but I am out of that loop.

Thanks for busting the myth of people spitting on and denigrating returning Vietnam soldiers. Even then, Nixon knew how to divide and conquer.

Thanks, Laurie. All of which begs the question of how long the courts will tolerate the orange, spray-tanned monster spitting his s#*t over the public forum.

One of the thorniest questions of the Vietnam era for Americans at home was whether you could show support for the soldiers fighting the war while, at the same time, protest the war itself as immoral (as if morality and the savage ravages of war even belong in the same breath). In an intellectual and abstract sense, it was logical to do so: support the individual troops but not their mission. Where the rubber met the road that those soldiers walked, however, such a mantra often came across as disingenuous and condescending. Some combatants saw it as an arm around the shoulders, but with the uttered message being, “I’m afraid you’re engaged in — and risking your life for — a dangerous folly … Hope you make it back.” For the protesters, the key issue was the principle of peace; for the soldier, it was staying alive, hoping your sacrifice was doing some good, and living with the memories of buddies who died. Such are the realities of fighting a war and of the legitimate protest of war itself.

Thanks, Jim, for this articulate and thoughtful expansion of my single-issue look at Vietnam and the contradictions of protest. As we can see clearly and violently, with much nausea and heartbreak in Gaza, there is no simple position and no simple answer to the complexities that lead up to, and engulf organized violence. Of course, the underlying question of our involvement in Vietnam still remains unanswered: what were we doing there in the first place?