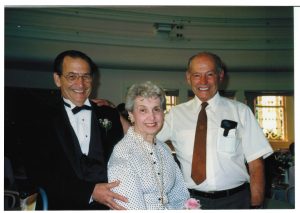

Rollie, 1992. In front of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.

My Aunt Rosalyn is tiny, just barely five feet. She’s formidable, shrewd, as tough as a general on a battlefield. I love her, despite her inflexibility and bossy nature.

She isn’t happy when her brothers marry non-Jewish women, and predictably takes a dim view of her son Donald’s tall, blonde girlfriend Sallie. One afternoon Sallie serves meat loaf, mashed potatoes and a simple green salad. Rollie is polite during the meal, but when Donald and Sally leave the room she asks me, "So what’d you think of that?” “Oh, it was fine,” I answer. "I call that Shiksa food,” she says.

I love her when she takes time to sit with me and ask me the questions that no one else does. I love her when she sends her annual birthday card with a check for five dollars inside — long past the point when five dollars means anything. I love her when I get older and realize how crafty, autocratic and manipulative she is.

I even love her after she’s horrible to my mother Roberta and refuses, during a decade-long estrangement, to consider that her own vanity has fueled her foolish grudge.

My brothers and I call her Rollie, at her request, and in my first four and a half years, before our family moves from Chicago to California, Rollie is a frequent, indelible presence in our lives. I remember thinking very early that my mother, grandmother and Rollie were a female triumvirate, each one vital and significant. I thought everyone had a Rollie.

She was born Rosalyn Lina Guthmann in 1903, the oldest of three children and my father’s senior by 11 years. Her father David Raphael Guthmann, was a harsh, short-tempered bully who ran the household like a dictator, keeping my grandma Sadie on a short financial leash. By her own admission, Rosalyn takes after her father far more than she does her mother.

In addition to my dad Marvin there’s another brother, Dave. Three years Rollie’s junior, he’s the black sheep of the family, a loner and misfit. Marvin is her adored pet for the rest of her life: Even when he battles with my brothers and me and unleashes horrible flashes of violent temper, she remains blind to his flaws.

At 25, Rollie marries Dick Harris, a man 10 years her senior and so acquiescent to her wishes and expectations that, for all I know, they never fight. “He had the most wonderful disposition of anybody I ever met,” she enthuses several years after his death. “That man never said anything not nice about anybody.”

In the 1930s and ‘40s, the Harrises operate a radio-repair shop called Radio Doctors. Soft-spoken Uncle Dick is ostensibly the co-proprietor, but everyone who steps foot in the establishment knows instantly who’s the boss. Rollie keeps the books and the payroll, stands behind the technicians while they fix the radios and decides when, if ever, employees get a raise.

Rollie and her husband Dick Harris at the Chicago World’s Fair, 1933. “He had the most wonderful disposition of anyone I ever met.”

“I was the one that had to fight,” she remembers. “Fight with the suppliers, fight with the customers. Dick would just say, ‘Wait, I’ll call the boss’s daughter.’ That was me, ‘the boss’s daughter.’ ”

“She was so tight with the buck,” my dad recalls, “that your Uncle Dick used to steal a couple o’ bucks out of the till when she wasn’t looking.”

Rollie has two sons, and both take after her far more than they do their father. She’s the disciplinarian: “If the boys were naughty Dick told me, ‘You ought to punish them.’ He never did. So I would go in the bathroom and sit on the toilet seat and spank them. Then I’d go in my room and cry.”

Bob, her first and favorite, dutifully calls his mother every day of his life. Donald, her second, shares her apartment throughout his forties and fifties. Most nights he sleeps at his girlfriend Sallie’s place, but comes home for breakfast, goes to work and is back at Rollie’s for dinner. The bonds are fierce.

Rosalyn is a man’s woman and much tougher on women than she is on men. Her siblings and children are all men and the women they marry are subject to a high grade of scrutiny. She sees herself as having a man’s competence and self-reliance and considers most women weak, overly emotional and untrustworthy.

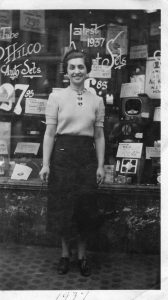

Rollie, 1937. At Radio Doctors, the radio repair shop she operated in Chicago. “I was always a businesswoman.”

“I’m so glad I was born a woman,” she tells me once in a typically unedited moment, “so I didn’t have to marry one.”

She isn’t happy when her brothers marry non-Jewish women, and predictably takes a dim view of Donald’s tall, blonde girlfriend Sallie. One afternoon at Donald’s house in suburban Chicago, Sallie serves meat loaf, mashed potatoes and a simple green salad. Rollie is polite during the meal, but when Donald and Sallie leave the room there’s a disapproving sneer on her face. “So what’d you think of that?” she asks. “Oh, it was fine,” I answer, cautiously noncommittal. “I call that Shiksa food,” she says, her upper lip curled in disgust.

And here’s another thing about Rollie: she is frugal to an extreme. Pathologically parsimonious. She never buys furniture or household items, but brings stuff home from the thrift store where she volunteers. Her sofa and chairs are covered in plastic. Even the arrangement of plastic grapes on the coffee table is shielded against dust by a plastic tea cozy. Rollie doesn’t travel, rarely buys nice clothes for herself and never dines in expensive restaurants.

Once during a visit to Chicago, I need to call the California hospital where my mother has just had hip surgery. Rollie instantly orders me to charge the call to my home phone number. “All right,” I say, “but I need to call directory assistance to get the number.” (The Internet is still pre-natal.) “Well,” she counters, “that costs money, too.” So I charge the 50-cent directory assistance call to my home number.

When her son Bobby takes her out for dinner, she orders enough for two, barely touches her food and takes the rest home in doggie bags to last through the week. This is all perfectly loony, because in fact Rollie has tons of money – far more, we later discover, than anyone suspects. And she has it precisely because she never spends it.

“You’re a wealthy woman,” my dad tells her. “Why don’t you enjoy it?”

“I don’t know how,” she answers, a bit mournfully.

During her annual visits to California, Rollie initiates a game called “Store.” Out comes the card table, which represents a sales counter in a retail establishment. My brothers and I gather random items from around the house, arrange them on the sales counter with price tags, and await our first customer.

The door opens and Mrs. Harris enters with great dignity — posture erect, carrying a purse full of Monopoly money. “Hello, young man,” she intones with efficient formality. “May I see your merchandise?” This is our cue to describe the items on the table and their designated price. Bartering may ensue, then an exchange of money – here we learn to carefully make change — and in the end our satisfied customer brings her commerce to a close. Purse snapped shut, head held high, she bids us a gracious good day. An impeccable performance.

Thrift, caution and the prudent budgeting and investment of money are everything. “You don’t pay any attention to finance, Eddie,” she says with grave concern when I’m in my forties. “You should. Finance is very important – it has to do with almost everything. The reason Hitler got so strong is he was a sharp guy and he figured, ‘The Jews have the money and I’m going to get their money.’ Why do you think he wanted to kill all those Jews? He was envious. He wanted what they had and baby, he got it.”

I have a soft spot for Rollie, because we have a mutual affection society and because she is so dramatically unlike anyone I’ve ever known. In my adult years, I visit her periodically and in 1987 bring a video camera to interview her about her life. She speaks with warm affection of her four grandparents, all of whom were living in Chicago when she was young, cries when remembering my dad as a baby and again when she describes my grandmother, so undervalued by her husband, as “a lady.”

On another visit, I videotape Rollie at the Michael Reese Service League Thrift Shop, where she’s volunteered every Saturday since 1953, and record her busting the store manager’s balls and skillfully mesmerizing her favorite customer into another purchase (“She buys a lot of stuff,” Rollie confides in a stage whisper).

We drop by the Field Museum of Natural History where Bushman, a taxidermied gorilla and former star attraction at the Lincoln Park Zoo, is preserved inside a large plexiglass cube. Bushman, not coincidentally, was my mother’s pet when he was a baby in Cameroun. She was a missionary’s daughter and born in Cameroun — but that’s another story.

After paying homage to Bushman, Rollie and I are resting on a bench. “Look over there,” I observe. “They’ve got an American Indian exhibit.” “Oh, I don’t like Indians,” she replies. “They all want something for nothing.”

Later the same year, Rollie flies to Seattle for my brother Dave’s wedding, where the incident occurs that frosts her against my mother. As the wedding is about to begin, my parents are seated in the front pew with Mom’s sisters, Esther and Winifred. Seeing that my Uncle Dave is in the second row with his family, Mom suggests Rosalyn sit with them. Seems logical. Rollie complies, but considers this an outrageous affrontery – as the family matriarch, she expects the ultimate in deference — and seethes with resentment.

When they are finally in the same room several years later, Mom approaches to hug Rollie, who stiffens and steps back. “I see you have a very short memory,” she sniffs. My dad spends years trying to reason her out of her grudge, and when Rollie complains to me about her perceived slight I remind her that my mother – a Guthmann by marriage only — visited Grandma every day in the nursing home where she died. “Can’t you let that guide your opinion of my mother?” I argue. “She treated Grandma as if she were her own mother.”

It’s useless: there is no dissuading Rollie from a fixed position, especially as she ages and becomes correspondingly more rigid. Everyone in the family is afraid of her. If she ever entertains doubts regarding her intellect, competence and superior judgment, I never see them.

I didn’t see Rollie the last five years of her life. I’m told she is greatly diminished, and when I call my cousin Bobby he discourages my visiting. She has a series of live-in caretakers, but her kvetching and demands are so harsh that one by one the workers quit. Eventually, the agency refuses to send anyone.

Rollie dies in 1999, having seen nearly the entire 20th century. A month later a letter from Donald arrives in the mail. I assume it’s an inheritance check — Rollie always promised me I’d be remembered in her will — but when I open the envelope I’m disappointed that my bequest is just $10,000. I’m embarrassed to say I expected much more, even hoped it would expedite my retirement. Soon I see this as a life lesson: Never, ever adjust your life in expectation of a gift. That’s the poison of greed.

When she dies, everyone is astonished at the size of her estate. We’ve always known Rollie invested wisely and hoarded her money with a miserly rigor — but $30 million? Seventy percent of it goes to the IRS because she didn’t shelter it, the rest to her sons and grandchildren. There’s also a generous gift to the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago, which displays its gratitude by posthumously naming a baby gorilla “Rollie.”

I think of Rollie often. I miss her unconditional love; the tender way she shared stories about my forebears; her exasperating, proud and imperious, take-no-prisoners way of walking through life.

Edward, it was delightful to meet your Aunt Rollie through this beautifully-written story. She sounds like an amazing woman. And the pictures make it even better. I had to laugh at her comment about shiksa food – that sounds like something my grandmother, or even my mother, would have said. Thank you for sharing her with us.

Thanks!

This was a great read, Edward, and I felt like I knew Rollie and your family. Yes, loved the part about the shiksa food. It’s always fascinating to read about someone so unforgettable!

Thanks!

Thanks a lot!

Wow Edward, your aunt Rollie was quite the character and certainly made a big impression on you!

Her comment about shiksa food was funny. I was once at the other end of a comment like that.

In my early cooking days when my repertoire was even smaller than the slim one it is now, an Italian friend was coming to.dinner. I told her that in her honor I was making pasta, but when she saw my meatballs and spaghetti she said, , “Oh, Jewish pasta”.

Thanks for the kind words. Ouch, that “Jewish pasta” line had to sting.

What a lovely and well written profile of a unique and formidable woman! I remember when you interviewed Rollie and made the short film about her. I also remember being impressed by her long tenure at the hospital thrift shop. I guess what stands out for me in your story is how, despite her abrasiveness, she was always tender and kind towards you. I wonder if she saw something in you that drew you to her, a vulnerability that perhaps neither of your brothers had. I get the sense that you and Rollie were kindred spirits, even though your personality is very different than hers. It’s wonderful to have a relative with whom you have a special affection, and who can teach you something about life…and finance! 🙂

well done, E!

Thanks, Carol! I think what bonded us is a strong interest in each other. That and

a blood connection.

Edward, what a fascinating study of your Aunt Rollie. You really summed her up in your title, so I was anxious to read about such a complex woman (particularly the Prussian general part). You did not disappoint, but took us through, step by step, her life story and your interaction with her. Though my mother wasn’t nearly as accomplished, she was just as rigid and unfiltered (a year before she died, far along with dementia, I begged the folks in her nursing home not let her vote in 2008, but it was too late. A proud FDR liberal her whole life, she told me she’d voted for McCain because she wouldn’t vote for the “Schwarze”, not understanding a thing about what either of the candidates stood for). My mother also was frugal and left a nice inheritance (not $30 million…my goodness!) when she died.

You paint a vivid portrait of Rollie. It is good that she was tender with you, even if she couldn’t be with too many others. You have those good memories. Thank you for sharing them with us.

Thank you, Betsy!