I’ve worn glasses since I was a kid. I was a vain and insecure adolescent, but I didn’t much give a damn for wearing glasses. They gradually become a fact of life, like zits. Nobody called me four-eyes or kicked sand in my face. Besides, I liked to see the world clearly after a year of pre-prescription blur.

I didn’t much give a damn for wearing glasses.

I tried hard contacts when they first came out, but I kept losing them under chairs and tables or dust would get under them, so I’d pop them out and stick them in the watch pocket of my Levis. When I needed to see again, I’d swish them around in my mouth and slide them back onto my eyeballs. That kind of ocular abuse didn’t seem viable in the long run, so I reverted to glasses.

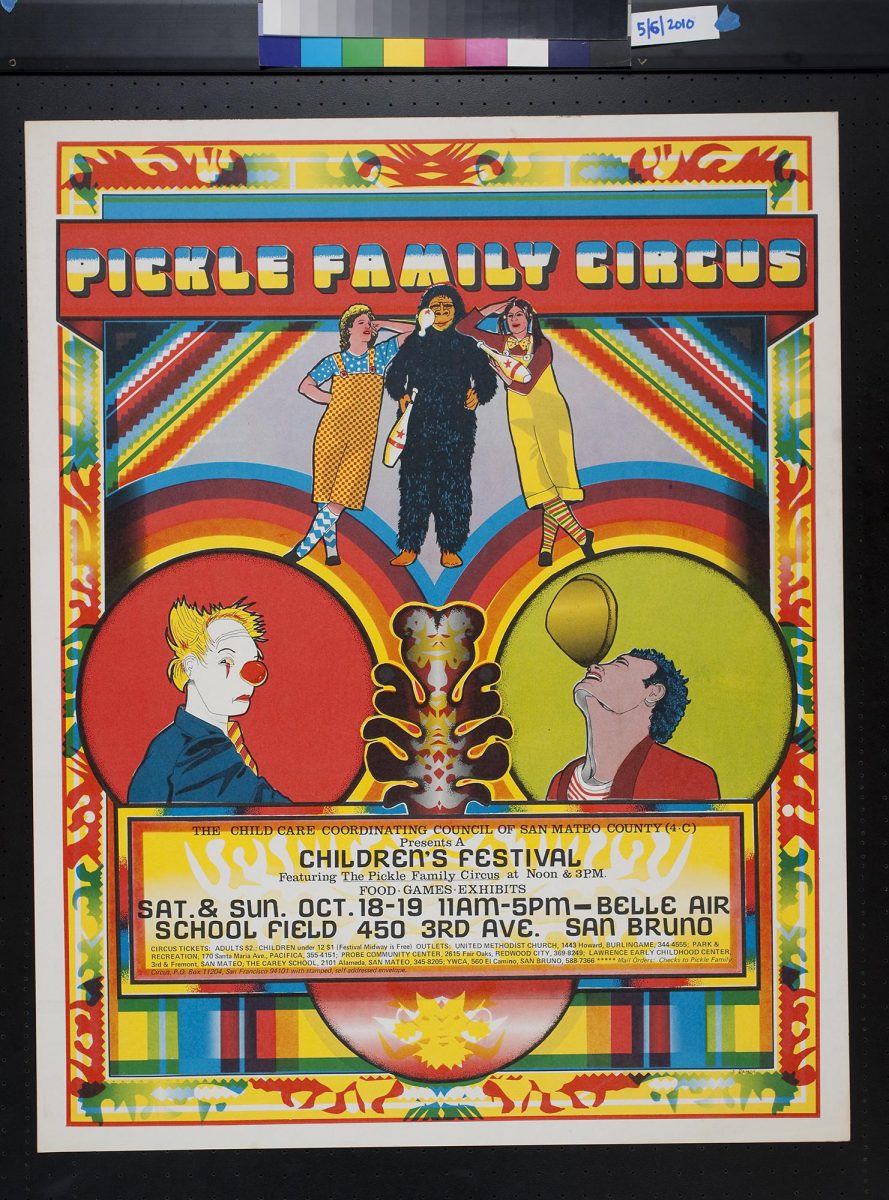

When I toured with the Pickle Family Circus, we’d be on the road for six to eight weeks, traveling in a vehicle caravan up and down the coast from town-to-town. I had an old Chevy station wagon that accommodated a tidy, solo futon, a cooler, a duffel bag and, of course, my axe. A musician never lets his axe out of sight. My amplifier and costume rode in the truck with the rest of the circus gear.

When I toured with the Pickle Family Circus, we’d be on the road for six to eight weeks, traveling in a vehicle caravan up and down the coast from town-to-town. I had an old Chevy station wagon that accommodated a tidy, solo futon, a cooler, a duffel bag and, of course, my axe. A musician never lets his axe out of sight. My amplifier and costume rode in the truck with the rest of the circus gear.

We’d pull into town on a Thursday, drive to a pre-determined spot (we had an advance person), assemble the bleachers rack-by-rack with boisterous teamwork, lay down a bright blue canvas floor with a big red star, circle the one-ring stage, rig the trapeze and backdrop, and assemble the bandstand hopefully under the shade of a tree. We’d surrounded the whole spinning cirque de Pickle Family with a red-and-yellow canvas wall — they don’t call it a circus for nothing — and call it a night.

Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, we’d unleash our unique brand of circus on unsuspecting but respective audiences. Sunday night, we’d strike the circus rig. The band might play in a local joint, or we’d hunker down for the evening at the now-empty circus site. The next morning we’d take off to visit nearby friends or head to the nearest national park to camp, relax, and explore.

When I lost my glasses on the second week out, there wasn’t much I could do about it. We didn’t stand still long enough for me to acquire another pair, even if I had a prescription.

When I lost my glasses on the second week out, there wasn’t much I could do about it. We didn’t stand still long enough for me to acquire another pair, even if I had a prescription.

At first, I panicked. From my underwater POV, reality became indecipherable, from the cars and semis whooshing past, to the road signs, the audience’s faces, to the notations on my music charts. But it’s difficult to stay uptight when you’re traveling around with a bunch of talented, hard-working freaks who improvise around impossible circumstances as a way of life.

I could make out the performers easily enough. They did their acts underwater in my own personal sea, but I knew the characters and their routines. If I didn’t know a tune, I’d just slide up close to my music stand and squint. I knew all my fellow performers by their clothes, hair, voice, and body language, so recognition wasn’t a problem.

Touring by nature assaults you with too much information about your fellow artists. Accordingly, my undersea myopia forced me into a blissful ignorance. If only I couldn’t hear, I thought. But then I couldn’t play, so I had to settle for the myopia.

All went well until one Sunday night after we’d played the weekend in a Corvallis, Oregon fairground. It had been a full moon weekend. When you are in the theater, you become aware of phenomena that might explain the ever-changing mysteries of performance. Granted you’re performing off a script or, in this case, a tightly choreographed 90 minutes of circus acts with music. So, when shit happens you look for why. We took the waxing moon as an explanation.

The whole weekend had been weird. The audience felt unpredictable and restless. Props broke. A juggler twisted an ankle. A drunk caused trouble on the midway, a rare circumstance when the midway consisted of fund-raising booths for daycare centers, organic farmers, and environmental groups.

The whole weekend had been weird. The audience felt unpredictable and restless. Props broke. A juggler twisted an ankle. A drunk caused trouble on the midway, a rare circumstance when the midway consisted of fund-raising booths for daycare centers, organic farmers, and environmental groups.

Regardless, the weekend ended, and a small group of us started out for Humbug Mountain State Park, and a beautiful spot I had discovered the year before. We began climbing into the foothills, four cars in caravan, me in the lead, squinting my way along the path to Humbug’s sublime alpine, creek bed Nirvana. Even with the north country’s long summer days, darkness descended as the canyons steepened around us.

Once away from the flatlands, the road signs thinned but I zero’d in on the familiar park signs that flared in the headlights. I became so intent on using my mole-like sniff-and-recall navigation technique that I failed to notice that the headlights behind me had disappeared.

Once away from the flatlands, the road signs thinned but I zero’d in on the familiar park signs that flared in the headlights. I became so intent on using my mole-like sniff-and-recall navigation technique that I failed to notice that the headlights behind me had disappeared.

I pulled off onto a gravel turnout and waited. Had one of my compatriots broken down? Had I driven blithely uphill, numb to the horns and flashing lights that might have signaled distress? Had they turned left when I had taken a right fork? Had I taken the wrong fork? Beset by doubts, I turned around. I knew they hadn’t driven past me.

I groped my way down the dark mountain, my headlights the only sign of life. I had passed a roadside bar, the last commercial establishment before the Humbug National Forest imposed its wilderness on the world. Maybe they had stopped there.

Not a car had passed me going up the grade. Gliding downhill through the darkness, my mind began playing tricks on me. I had been abandoned on the mountainside like Oedipus. Had I been abandoned to prevent me from sleeping with my mother? I didn’t want to sleep with my mother.

Had they all driven over the side of the mountain, like three blind mice, following one another’s taillights into oblivion? Like Oedipus, I was blind. Besides, losing one’s glasses doesn’t compare to sleeping with mom or gouging out your eyes. I had to get a grip.

Through a stand of pines, I caught a glimpse of a large, orange fireball, floating in the distance. Was I hallucinating? Had the nuclear holocaust begun? Was I being tracked by aliens who could prey on my sightless condition to kidnap and dissect me?

The glowing orange ball disappeared behind a ridgetop. As I squinted after it, searching through the haze of my naked vision, I nearly sideswiped the bright yellow VW bug owned, driven, and lived-in by the vivacious roustabout, Zoe. And there they were, the tiny caravan of compatriots, gathered along the rail of an uphill turnout, oohing and aahing at the fuzzy orange moon.

So caught up were they in their moonlight reverie, it hadn’t registered on them that I had disappeared.

So caught up were they in their moonlight reverie, it hadn’t registered on them that I had disappeared.

Bathed in the bright light of the full June moon, all was forgiven. Reunited, we made our way into Humbug, past the padlocked ranger’s gatehouse and on to my creek side campground, empty but for us. We pulled up, lit a barbecue pit, ate, drank, laughed and tumbled into our various makeshift mobile beds.

From that point on, I resolved never to drive blind again at night. I never did sleep with my mother, but I did discover that — after weeks without glasses — my vision had sharpened considerably to the point where my subsequent visit to the optometrist felt like surrender. Glasses. Never leave home without them. Humbug.

# # #

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

As always Charles you spin a great tale from your adventurous past.

Thanx for taking us with you on that blind ride up the mountain!

Thanks for reading, Dana. Myopia can be a good thing, given the right circumstances. Given the wrong circumstances, myopia sucks.

Wow! As someone who has been horrifically nearsighted for most of my life, I am blown away by the idea that you functioned for several weeks – and even DROVE A CAR – without your glasses. This is quite a tale! And the moral seems to be that it’s okay to forget (or lose) the things that you think you can’t leave home without.

Thanks, Suzy. Jeez, and I thought the moral was “don’t sleep with your mom or you’ll go blind on a mountain.”

Wow, Charles, nevertheless you persisted. I would have been terrified to drive like that, but I love your story. I was farsighted until my cataracts kicked in, so most of my life I could drive without a problem. Now that I think about it, several years ago the cataract in my right eye bloomed very suddenly, and because I was caring for my partner during his long illness, I hadn’t realized it until I had to go home from the ER at 1 AM. The freeway was a blur, the lights were halos, and thank goodness for a very distinctive lighted sign near Great America to guide me.

Night driving was impossible. The rest was a blur. Regardless, we had a great tour.

I’m with Marian. Terrified feels like the appropriate word for this blind mouse. I’ve worn glasses since the age of 8, hard lenses at 13 (yes, I did the spit on them routine, but NEVER put them in my pocket, unprotected…good grief Charlie!), then my eyes dried out in 1990 (while nursing an 8 month old in January and my father had just died; I assumed it would be temporary, alas, it was not). I moved to gas-permeable lenses, then soft lenses, then saved them for going out at night. Then, when all hope failed, I had PRK surgery (a fore-runner of LASIK), which worked OK, but no one told me that I ALSO had astigmatism, which was not yet legal to correct for. Damn. And of course, I lost all my up-close vision (i was already wearing reading glasses over the contacts – my vision is just horrible). I can’t really thread a needle, reading gets more and more problematic and my eyes are more and more dry.

But driving as you did in the dark with no glasses! I am stupefied, but that red moon does sound entrancing. Please don’t leave home without your glasses (or sleep with your mother).

Thanks, Betsy. I really didn’t have a choice but to proceed with the tour, and my sight did improve. Re lens abuse, ‘Good grief, Charlie’ indeed! I think of that carelessness as originating from the same sense of impermanence and immortality that is keeping teenagers from getting vaxed. But the stakes are so different. Scratched lenses versus death. I won’t sleep with my mother.

This was another of your great stories, Charles. I thoroughly enjoyed it although the thought of driving in your condition is terrifying.

Thanks, Laurie. Sightless driving, yes, terrifying but I was immortal and insane at that age. Besides, I had no choice. The show must go on. And go on, it did!

Thanks for this story about the Pickles–I saw them (you?) and enjoyed the show many times, including so early in their career they were just a couple of jugglers in Golden Gate Park working on a routine (was it Peggy and the guy?). Of course you would improvise when life handed you a challenge (like not able to see), Oedipal or not. I love that you all headed to the campgrounds after shows. That big orange moon–maybe it was just the atmosphere but hey, maybe it was a lunar eclipse! Glad you all found each other and story ended well, and you told the tale.

I was there at the beginning, so yeah, we probably occupied the same spot on the space/time continuum for a coupla rounds. You were watching Peggy Snider and Larry Pisoni, both of whom were in the Mime Troupe with me a few years earlier. They are both remarkable people, and were then. Both their offspring have carried on the tradition in the most far-out and creative ways — Lorenzo Pisoni is an actor and physical comic, does everything from TV to his own one-man show, Humor Abuse. Peggy’s daughter, Gypsy created and runs Les Sept Doights theater company out of Montreal.

Those tours were wonderful. Just as we had burnt out our performing chops, away we’d go to the wilderness and just as we bored of the countryside, we were off down the mountain to the next town.

What a great story from a vantage point — running away with the circus — that I have only imagined. And you unwound it beautifully, and suspensefully to a delightful happy ending. That said, as others have noted, I can’t think of a “can’t leave home without it” object more essential than glasses to a nearsighted (I assume) driver. Please assure me that, being gracefully mature rather than recklessly young, you now always have a spare pair.

I do have a spare pair of glasses these days, John. I can’t brag about running away to the circus because I helped found it, ‘way back when the federal CETA program funded artists as part of its massive post-Vietnam recovery programs. That was, of course, just before the pendulum began to swing away from liberal consensus and a government that, amidst its imperialism, tried to keep a social contract with its citizens. Here’s hoping the pendulum will continue its tentative moves toward a swing back!

Yes, Peggy and Larry. It must have been in the mid-seventies when I was at UCSF, when we were among the fortunate random people in the park when they did their routine. When I moved back to the Bay Area in 1980, I was amazed that they had become a whole circus. Great memories, and much joy you all have brought to people!

Yes, your timeline is right. By end of 1976 we had become a full-fledged circus with clowns, jugglers, slack wire and trapeze aerialists. The clowns were really the core of it, Larry, Geoff Hoyle, a Brit physical comic, and Bill Irwin, who went on to fame and fortune on stage, television. And the kids, Lorenzo and Gypsy became part of the act, a Japanese jazz dancer who became a gorilla, you know… everything but the tortured, imprisoned animals.+