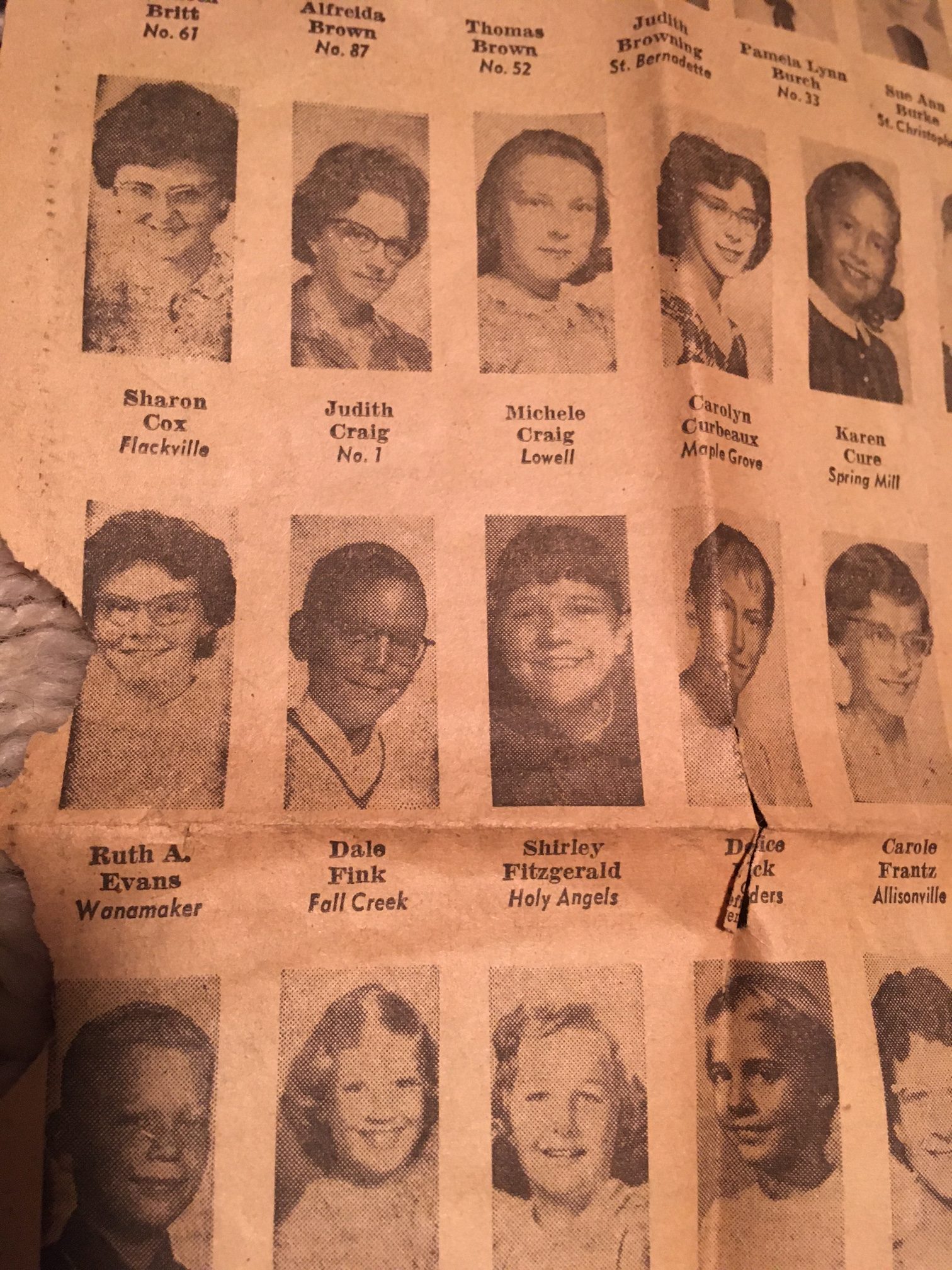

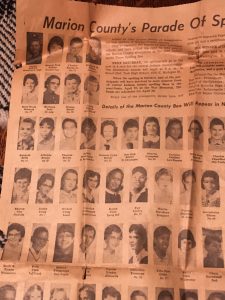

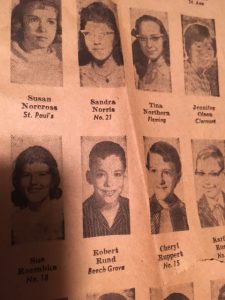

Pictured with other central Indiana contestants in the Indianapolis Times, April 9, 1961

In 2019, as I turned seventy years of age, I found myself making a list of the “top events or experiences of my life.” The very first entry was “Sixth Grade Spelling Bee.” This essay is my effort to interrogate that moment. What made the spelling bee—becoming champion of my elementary school and then participating in two rounds of a Central Indiana bee–so exciting and so memorable?

Floating somewhere unknown, however, was the fateful word gluttony, gearing up to topple me at some future moment when I might bite off more spelling splendor than I could chew.

The satisfaction of winning the spelling bee championship at my school was certainly enhanced by a buildup over a few years. Only sixth graders (the highest grade at Fall Creek School) participated, but starting in grade four, we all listened over the Public Address system to the final rounds, held in the principal’s office. Evidently, someone had decided it was important enough that teachers were instructed to drop whatever subject they were working on and have all their students sit quietly and listen to the denouement of the annual bee. Those of us in the fourth and fifth grades listened solemnly as the principal introduced us to the four to six sixth-graders remaining at the conclusion of the bee, and then proceeded to challenge them with the words that would determine the champion.

The use of the principal’s office definitely elevated the excitement level. As at most schools, students associated his office primarily with discipline, not with anything positive. I am aware now of schools where a student is invited each day to lead the Pledge of Allegiance and others where students get a turn to broadcast the daily announcements from the principal’s office. But Fall Creek pupils did not have even those rudimentary encounters with the principal’s office as a student-friendly environment. It was a forbidding place, for discipline and for important business that involved teachers being summoned there from time to time.

The prospect of earning my way to a seat in this mystery-laden, off-limits realm was no doubt part of what enchanted me about winning the spelling bee. As I listened to the final rounds of the bee in the years prior to my own eligibility, I built up a desire to win one of those coveted spots.

It is hard for me to say what made me a good speller, other than the fact that I was always more interested than many of my peers in words. For instance, my mother regaled me in later years with the story of the day I came home excitedly from first grade, telling her, she thought, that I had a new tooth. What I actually was conveying was that “we got a new too today!” That is, we already knew about the word to, as in “Dick and Jane go to school.” And we already had learned about the number two. But this day Miss Peterson had taught us another word with the exact same sound and its own distinct spelling: too.

About that same year, I was having a conversation with a friend and he made an assertion that I questioned, and, drawing on the vocabulary I was building through literature, I said, “I dopt it.” “What do you mean, you dopt it? You mean you doubt it?” “No,” I explained. “It’s a word that means almost the same as dout but it has a b in it: d-o-u-b-t. I dopt it.” He told me, “that’s how you spell dout! With a b in it.” I didn’t believe him but I was able to confirm it later.

There were three sixth-grade classes at Fall Creek School, located in a township north of the city of Indianapolis. The annual spelling bee was the only event I can remember for which the teachers crowded all 65 to 70 students into one of the three classrooms. I guess the custodian brought in folding chairs to (just barely) accommodate everyone. Wanting to emerge as number one in something from that entire cohort must have been another part of my motivation. I was nearly a straight-A student—but report cards were mostly a private matter. I wasn’t a bad athlete—but far from the best. When it came to spelling, there could be only one champ. I wanted it to be me.

It didn’t take long for the size of the population to better match the size of the room, as many students misspelled words in the very first round. Once a dozen or so kids were out, one teacher left to bring them to another room and more would file out as they missed words. I guess they were given free time to do homework, read, or draw. They probably weren’t checking their social media on their electronic devices. (That’s a joke for people who may be reading this in 2050, who may need a reminder that the world did not have portable devices, nor did the Internet exist in 1961, when this story takes place.)

I don’t remember any of the words I spelled or any of the ones that caused other students to fall by the wayside. But I do recall that Pete Whitten was the final contestant besides me, sitting in the principal’s office near a console that was capturing and broadcasting our voices. I know there were two other students who also made it there, but they didn’t last very long. Pete and I went back-and-forth, spelling a few words correctly And then he missed a word, and I spelled it accurately. And that was it: I was the champion!

I am sure I was given accolades by the sixth-grade teachers and the principal and by my classmates as well. But in my memory, the excitement of being the spelling bee champ shifts quickly in its focal point from the school to my family. For it was my mother who proceeded to help me prepare for the Regional competition, by giving me words to spell each night (I had never prepared for the bee at the school), and it was my Mom and Dad who accompanied me to the two Saturdays of competition, where I met up with all the other winners from cities and towns around central Indiana.

The parents could not sit with the spellers, of course. Family members took seats in the balcony and the rows in back, while spelling contestants were assigned seats in the front rows of an auditorium in downtown Indianapolis. We had numbers, and each contestant would walk up on stage when it was our turn and stand in front of a microphone as the reader pronounced the word. You could ask questions, widely known to the public now, as ESPN has been broadcasting the national spelling bee; the permitted questions have not changed in sixty years! “What is the definition, please?” “Can you please use it in a sentence?” “What is the derivation of the word?” “Are there any alternate pronunciations?”

I spelled four or five words correctly that first Saturday, and that was enough rounds for the contestants to be reduced from nearly 200 down to fewer than 100. Once again, I retain no recollection of words I spelled correctly. Floating somewhere unknown, however, was the fateful word gluttony, gearing up to topple me at some future moment when I might bite off more spelling splendor than I could chew.

I have scant memories of other contestants or their words, from either the first or final Central Indiana round. I do know that I was seated next to a boy named Robert Rund in the finals: as people who always loved the sounds of names, my parents remembered and repeated his name for years, even for decades afterwards. I also recall vividly one moment in the competition: a lean African-American girl wearing glasses and a plaid skirt was presented the word collegian. She spelled, “c-o-l-l-e” and then turned to the panel of judges and inquired, “gian?” It was apparent to me that she was asking if the part of the word that she had not yet spelled was pronounced gian. But the main judge heard it differently, and he rang the bell and said “that is incorrect,” which signaled for her to exit the stage and rejoin her family in the audience rather than return to her seat. But the girl stood her ground gamely and said, not angrily but quizzically, “I haven’t finished spelling the word yet.” A member of the panel, after conferring with the others, asked, “Did you say the letters G-N?” She said “No, I was just saying the rest of the word.” Miraculously, they accepted her explanation, and gave her a redo. She started over and spelled “c-o-l-l-e-g-i-a-n,” and said the word, just as required. The bell did not ring, and she resumed her seat among the contestants.

I made it through three rounds of the finals; there were still between 50 and 60 spellers in the seats when they presented me with the word gluttony. I had never encountered the word; the only question in my mind was whether or not to double the t. I asked for the definition, and then the derivation. When a judge explained that it came from the Latin glutto, I noticed that he pronounced it with a long u sound. That sound convinced me he was reading “gluto” with a single t, reasoning that if the Latin word had a double-t, he would have pronounced it with a short-u sound. “G-L-U-T-O-N-Y,” I spelled and then pronounced the word. I heard the bell and the devastating words, “that is incorrect.” It was a rapid end to a glorious dream of going all the way to Washington DC for the national competition.

On that list I generated, there is another entry that sheds light on why becoming the Spelling Bee champion was deeply meaningful to me. I wrote, “going to lunch at Duke’s with my parents, in conjunction with the spelling bee.” I was the second brother in the family, and a “middle child.” There wasn’t much as a kid I ever got to do outside the house with Mom and Dad that didn’t involve my older brother Leon. The spelling bee was one of those rare opportunities. It wasn’t just that they (mostly my mom) helped intensively with the one-on-one preparation, and that they set aside their usual weekend plans—which, for my Dad, meant cancelling his usual Saturday half-day at the law office. It was also “lunch at Duke’s.”

I don’t remember a thing about the contents or quality of that meal—I have a vague recollection that it was something of an old-fashioned diner–but I knew that Duke’s was one of the places my Dad would go to lunch during the work day. And that made being taken there by my Mom and Dad as awesome as getting to be in the Central Indiana finals of the Spelling Bee itself.

My sister was a second-grader when I was in sixth grade, and she remembers that she also got to go to Duke’s, as they had brought her along to attend the Bee. Leon, who was in junior high, must have made plans of his own. (Hugh and Laurel weren’t yet born.) So Elaine was there, but she wasn’t the reason we were having lunch at Duke’s. I was the reason. I was the champion of Fall Creek School. I was being taken to eat at one of my dad’s lunch spots. It didn’t matter what we ate, or how much. I could never get too much of that kind of memory.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Well, I would certainly not have recognized you from that picture! This is a lovely story, starting with the list of the top events or experiences of your life. I hope we will get to hear about more of them on future prompts.

I love the detailed description of how the spelling bee was conducted at Fall Creek School, including your feelings about the principal’s office. Also your earlier word history with “too” and “doubt.” The excitement of winning the school bee, then going on to the regional bee, and then . . . being felled by gluttony. Your logic about the Latin word was well thought out, but only by rules of English pronunciation, because there is no short u in Latin. Oh well, you’ll always have Duke’s.

Thanks for the comments on the various details and for your explanation about the Latin pronunciation. I tried to find a picture of Duke’s but it seems to not exist anymore–except in my memory. And I guess that’s what you meant anyway.

I love all of the detailed description in your story, Dale. It evokes that time before social media when things were simpler and a child could be delighted by lunch at Duke’s in his honor.

I especially enjoyed your description of the principal’s office, Dale, and what that meant for school children of that time. Altogether a more innocent time, at that, and you must have felt very good about your mom giving you words to prepare, and that special lunch at Duke’s.

Wonderful recollections of the elaborate machinations we all went through in learning how to speak first and write second. Loved the acrobatics you performed over the word “dou[b]t.”

Dale, a rich and fond recounting of that special period in your life. I love the moment when you came home with a new “too”. Very sweet. I, also, remember listening to events of note on the PA system in my elementary school (like John Glenn’s flight…we were all transfixed).

But your spelling bee finals were an annual event and you give us “you were there” details, so we can picture it too. You were on a mission and your hard work was rewarded. You got to the state-level championship in Indianapolis. Bravo for you! Despite encountering GLUTTONY, what makes this recollection even better was the lunch at Duke’s with your family. That’s a memory to treasure.

A rather belated CONGRATS on the spelling bee Dale!

And bravo on your amazing power of recall. I can’t even name all my grade school teachers!