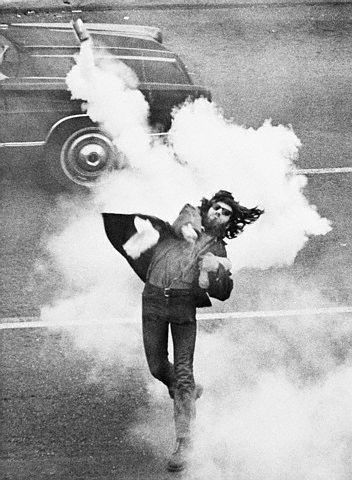

05 May 1970, Berkeley, California, USA — An anti-war demonstrator at the University of California, Berkeley throws a tear gas cannister at police during a student strike to protest the killing of 4 students at Kent State University. The Berkeley student demonstration is one of many across the nation in direct response to the killing of four Kent State University students by National Guardsmen during a Vietnam War demonstration the previous day. — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

My antiwar writing began in a theater. I was working on a new play and the antiwar movement of the 1960s came up in conversation. Several of the actors expressed amazement that there had been a determined movement to stop the war. One actor said something like “Wow! We just thought that all you guys did was smoke dope, get laid, and, like, drop out.” I felt my jaw clench and the veins on my neck popped into high relief.

I had already read much of the powerful library of fiction that came from Vietnamese and American soldiers who had fought each other and lived to tell the tale. But what about the war against the war? There was very little literature about the resistance.

I was aware that the accomplishments of the antiwar movement had been eroded by a booming corporate culture that had no time for the past and no room for resistance. And the actors’ ignorance about the antiwar movement reflected a long-term de-education of recent history. The Vietnam war demanded less each year in the nation’s history texts and television empowered law and order. Still, I was shocked by their response to the most powerful liberation movement in U.S. history. They didn’t even know it had happened! I decided to set the record straight.

I wanted to write about the resistance’s impact on the war, about the triumphs of feminism and environmentalism. We had broken the stranglehold on what was being taught at universities, demanded black and Chicano studies programs, womens’ studies. We had redefined the contemporary university as research and profit factories where students and faculty served as workers. With most of the rank and file faculty at our side, we had changed the curriculum!

I wanted to talk about all of that… and more! And so I sat down to write Gates of Eden, an episodic novel named after Bob Dylan’s stark song of corruption and decay. I felt that the resistance chose to stand outside the gates of Eden in defiance of a materialistic nation that called itself paradise while millions of Americans lived in poverty and while our leaders bombed a nation of farmers back to the Stone Age.

I wanted to portray the antiwar movement through the novel’s characters — their actions, their struggles, hopes and fears. Although there was plenty of sex, drugs, and rock and roll in those days, I didn’t set the story at rock concerts, or smoke-ins, or orgies. Nothing wrong with any of those things, but I drew from my friends’ and my own experiences as we became aware of two Americas — the gap between poverty and wealth, the connection between racism, the economy, and who was drafted to fight the Vietnam war.

Gates’ characters I modeled on those who planned and marched at gigantic protests and demonstrations. They devoured life in bedrooms and ratty movement offices connected by FBI-tapped phones and stinking of mimeograph ink. They gathered in universities, collectives, communes, on city streets, and broadcast their positions in underground newspapers. They weren’t hippies, rock stars, or dropouts. They were artists, writers, street fighters, Viet vets, free thinkers, strategists, lost kids, people who took a look at what was going down and picked up the gauntlet to resist. To rebel. And, of course, to love. They told a different story.

I also wanted to counter misconceptions about the antiwar movement promulgated by popular culture. I think most people knew about the 1960s from films. “Easy Rider,” “Running on Empty,” “The Big Chill”… These were made by people who were building their careers, not fighting The Man.

Granted, many of these artists were talented and well-positioned to make their films. But without having been there — in the streets, in the ratty Movement offices, in the jails, in the free stores, on the communes and collectives with nothing but spaghetti to eat — their stories lacked authenticity. Often – like “Running on Empty” — they echoed the mission of the establishment — to revise, belittle, and to render impotent the real power and success of the antiwar movement.

Gates’ first outline included everything from the origins of the civil rights movement to the Cuban Revolution to People’s Park and every person, place, and anecdote in between. I knew I had to narrow the field. But I had become re-obsessed with the huge tapestry of the 60s, with my own recollections and the people, places, and events of the time. I had to turn this historical laundry list into a human, character-driven drama, get rid of my own, preachy didacticism and let my characters tell their stories. And I had to tell it like it really was, not like the mainstream portrayals.

At the same time, a lot of people didn’t know much about the war, the antiwar movement, and its impact. I couldn’t just ignore history. Instead, I set out to carry it through the characters’ actions, words, and conflicts. I also added “Masters of War” chapters where readers get to spy on the power brokers, the men who made the decisions to continue the colonial war in Vietnam, to escalate it, and make it look like a war worth waging.

None of these characters are me. Or any of my friends. They’re all hybrids whose characters grew as I wrote. Some faded while others wouldn’t shut up. Madeline, for example, a young Greenwich Village poetess, jumped out of a Weegee photograph I was using to set a folk music scene in Washington Square Park. She just wouldn’t sit still and she wouldn’t shut up, so she became one of Gates’ major protagonists. I invented other characters because I wanted to represent the diversity of the movement, from returning, radicalized vets to COINTELPRO spies and conservative parents.

None of these characters are me. Or any of my friends. They’re all hybrids whose characters grew as I wrote. Some faded while others wouldn’t shut up. Madeline, for example, a young Greenwich Village poetess, jumped out of a Weegee photograph I was using to set a folk music scene in Washington Square Park. She just wouldn’t sit still and she wouldn’t shut up, so she became one of Gates’ major protagonists. I invented other characters because I wanted to represent the diversity of the movement, from returning, radicalized vets to COINTELPRO spies and conservative parents.

As I wrote, I hoped Gates would be an exciting book. Certainly, a lot of love, research, imagination, and hard work went into telling a largely untold tale. And, as with all novels, I hoped Gates would transport its readers into a different landscape so gripping and powerful and so delicious that they would make the journey from beginning to end.

# # #

*Adapted from an interview conducted on Pacifica Radio.

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

Thanks for giving us this fascinating story behind the story. I read Gates of Eden shortly after I first learned about it on Retrospect more than two years ago. I loved it! I gave it to my daughter to read before she took a college class on the Sixties. I had my book group read it, and discovered, much to my dismay, that since they are all younger than I, they didn’t know that many of the events in the book had actually happened. It was an eye-opener for them, as I’m sure it is for many people.

Madeline was my favorite character, so I’m glad to hear about her. I love that she jumped out of a photograph and wouldn’t sit down or shut up! Sounds a little like me at that age. 🙂 Maybe that’s why I liked her so much.

Thanks, Suzy. I’m glad to hear that you introduced this novel to generations. It seems that, after 50 years of history that war keeps rejoining the present.

Thank you for that point of view, Charlie. You were THERE and you speak with authenticity and time and place, about the beginning of the Movement and not the Hollywood version of it. We appreciate that clarity.

Thanks, Betsy. I had plenty of motivation to talk about the people, places, and events involved and probably a great deal to explore and resolve about my own position between war and resistance.

“Tapestry” is the perfect word for the richness of your novel, which weaves multiple characters, stories, and layers into a fine, unified fabric. Reminder to readers: You can order Gates of Eden by following the Amazon link at the top right corner of this web page.

Thanks, John. Coincidentally, Carole King’s “Tapestry” was one of three albums I had when living high in the Rockies of Colorado. No electricity, but a battery-powered phonograph brought music to the cabin.

Your timing (for me) is perfect, Charles. For whatever reason, I have been wanting to revisit the 60’s anti-war movement, but not in a purely historical fashion. And from the perspective of a contemporary who lived through it, not via a glossy, idealized popular movie. (Ironically, M*A*S*H may be the best anti-Vietnam movie out there,)

Finally, I continue to be in awe of those who, unlike me, actually write books, rather than just think about doing it. I always want to know from where they get their inspiration, both for characters and stories. All I know for sure is that there is no one way. So I particularly loved how your Retro story explained why and how you wrote “Gates of Eden” and what I would call your “multi-disciplinary” approach. I’ve just downloaded it to my Kindle (i.e., the check is in the mail) and I look forward to meeting Madeline, et al.

John, I’m delighted in your interest re: Gates of Eden! I kinda wrote it for us but I’ve also gotten good responses from Gen Xers on down. Gen Xers seem to fall into two categories. The ‘jeez, my big brother was into all that and I hated that I missed it,’ to ‘you guys were bums who ruined stuff for everybody.’

My students seem interested in the abstract, altho a remarkable number of them don’t know that anything of significance took place circa 60s.

Enjoy the read and would love to chat w/you during or after. Thanks again for your kind words.

Absolutely, Charles. I’m not sure exactly when I will read it — I tend to be fairly anal about reading my Kindle books in a FIFO manner (comes from working in accounting firms) — but definitely will.