J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the FBI from 1935 to 1972

The thing that troubles me, even though it is now 50 years in the past, is this: What was it like for my neighbors to have an FBI agent knock on their doors in December 1970 and ask questions about me? I’m less concerned about the several employers he contacted, or the teachers at my high school and other people whom I had listed as references in seeking work. But my neighbors?

What was it like for my neighbors to have an FBI agent knock on their doors in December 1970 and ask questions about me.

Most employers are used to answering questions about former employees. Although not necessarily Mrs. Romer. It seems like a stretch that the agent thought he would get valuable information from the woman at the Indianapolis Hebrew Congregation (IHC) who put me in charge of the audio-visual equipment at Sunday School during one semester when I was in high school.

They did not interview the supervisor of the Adams House kitchen at Harvard College, where I worked throughout my freshman (1967-68) and sophomore (1968-69) years. I used my social security number and paid taxes at that job, just as I did when I worked at the Post Office in Indianapolis in the summers of 1967, 1968, and 1969. They did interview the supervisors of the various postal stations where I worked. Wouldn’t it have been obvious to an investigator working for the federal government and with access to government records that I was the same person? And couldn’t one gain a better insight on my 1970 point of view and trustworthiness from speaking with the more recent employer, rather than the one from high school?

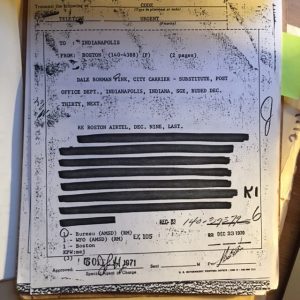

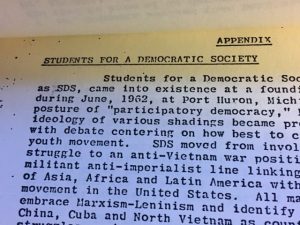

But there is this memo entered into the files on December 9, 1970, by the Indianapolis Bureau of the FBI: “Investigation conducted at Indianapolis, Indiana, has failed to identify the employee as being identical with one DALE B. FINK known as an active member in the Harvard-Radcliffe SDS group as referenced in Boston file number 100-35472. Indianapolis indices fail to reflect any information identifiable with employee. City, county, and state law enforcement agencies fail to reflect any information identifiable with DALE BORMAN FINK.” Remarkably, they were not unaware of this “other” Dale Fink; they just were not able to pinpoint that he was the same person.

Eight days later (Dec. 17), there is another memo that indicates they did overcome that gap in information, ”determined that FINK attended Harvard College, Cambridge, Massachusetts. In spring, 1970, he was engaged in SDS activities at Harvard involving sit in demonstrations. As a result of his participation he had been suspended from the University for a period of one year.” A memo called an AIRTEL, resembling a telegram, announces they are “converting case to full field investigation…Indianapolis will ensure that all background information contained in Indianapolis report…is directed to all interested offices expeditiously.”

Even in this “full field investigation,” the Boston bureau seemed to keep its agents on a tight leash. They checked with law enforcement in Boston and Cambridge, and also examined credit records (where I was missing in action) but as for Harvard, all their documented information came through various offices that kept records, but not from any personal interviews. They knew my major and my housing assignment but made no reference to any employment or classes or professors.

Of the employers they did interview, only one was brave enough to tell my father about it. Sam Chernin (whose name the FBI consistently misspelled in the file as Chuerrin) imported toys from Asia and sold them to U.S. retailers. His son Dave was at Yale while my brother Leon and I were at Harvard and Dave had for many years been one of Leon’s best friends. Our families both belonged to IHC and were close enough that they had lent me their old beat-up Volvo for a whole summer to get myself to work at the post office. More recently, I had needed work for a couple of weeks while waiting to be rehired at the Post Office for the summer of 1969, and Sam had generously offered me work in his warehouse. The job turned out to require a ton of heavy lifting, but paid a fair wage. According to the notes from Special Agent in Charge (SAC) Philip William Cook, Sam stated he had known our family for 20 years and that “Dale has always associated with only a high caliber of individuals” and that he would recommend me “for a position of trust with the federal government.”

Why was it brave for Sam Chernin to disclose to my dad that the FBI had come to see him? Because Mr. Cook told him it was illegal for him to disclose anything related to the investigation and that there would be consequences if he did so. It was scary to hear that. It meant there were others who were being questioned about me, but who had not risked violating the instructions from the agent. Who were the others? I would not find out—with one exception–until I obtained my file under a Freedom of Information Request in 1979.

The exception was Rabbi Saltzman. Special Agent Cook divided his reports on the people he interviewed into sections with subtitles; Neighborhood, References, Education, Employment. Saltzman was one of the References.

Under education, there were communications with the assistant principal of my high school, an English teacher I had my senior year and a French teacher I had for three years. Oh, to know what went through the mind of Mr. Goacher, who loved not only the French language but the theatre, arts, cuisine, and wines of France. He acknowledged that he had met my family and visited my home, and crowed to the agent that I was an outstanding student who had mastered the French language, and moreover that I had earned my way into the Indiana University Honors Program for Students in Foreign Languages and spent the summer of 1966 in St. Brieuc (which the report misspelled as St. Brieu). While answering questions about me and my family, did Monsieur Goacher pause to wonder what would happen if an FBI agent went around at some future time asking questions about him? Investigating and potentially disturbing his contented life as a closeted gay teacher? If he did, I bet he was smiling on the inside as he spoke to the agent.

The interview with Rabbi Saltzman was in the section called “References,” along with reports from three other men I had listed in applying for various jobs: a lawyer who shared offices and secretarial support with my dad, another lawyer who had been one of my dad’s best friends since I was born, and a Jewish builder who lived nearby, had boys the age of my brother and me, and had built our house. Rabbi Murray Saltzman (which the file misspelled repeatedly as Saltsman) had taken the pulpit at IHC during my high school years and was still there in 1970. Like Sam Chernin, he dared to defy the instructions of the agent and tell our family that he had been contacted.

In addition to being unafraid to tell us the FBI was investigating me, Rabbi Saltzman appears to have been the most loquacious of those interviewed—judging by the half-page required by the persistently succinct Agent Cook to write up what he said. I can imagine the rabbi welcoming the opportunity for discourse not only about me but about the state of the world and the need to repair it. He said he had visited our home on many occasions. However, in FBI parlance, nobody ever says or even states anything; they advise, as in “he advised that he has visited the Fink residence on numerous occasions.” Here is a further excerpt; just imagine the rabbinic inflection and the use of hand gestures for emphasis:

“He described Dale Fink as being an individual who is faced with the problems of maturing into adulthood. Dale Fink has shown a great desire to help the cause of mankind. Dale advised Rabbi Saltsman (sic) that he had participated in sit-in demonstrations of the President’s office at Harvard University. As a result of this participation, he was expelled from school… he was definitely opposed to violence…Fink stated there should be changes made in the present structure of the United States and that the students who are concerned with the future of America should be active in politics… Dale Fink has always shown a high degree of moral convictions…he could be entrusted with a position of trust in the federal government.”

For the record, Harvard did not expel (or require to withdraw for a specified period of time) anyone for a sit-in at the President’s office. My own requirement to withdraw for two semesters (with one suspended, but I stayed away the full year anyway) was for participation in an obstructive picket line outside University Hall, impeding access by administrators to their offices. I don’t know if the erroneous characterization came from the rabbi, or from the same agent who was unable to accurately capture the names of his informants.

To all these employers, educators, and other references who were approached by Agent Cook, I am deeply grateful. Each of them attested to my character and trustworthiness to hold a position in the federal government. I believe that each of them was able to endure such an interview with aplomb and with minimal stress. Rabbi Saltzman probably even enjoyed it and perhaps wished he could have preached a sermon about it.

But my neighbors? Larry and Jim’s father? Richard’s mother? Mrs. Schwomeyer? I still feel bad they had to answer that knock on the door.

Earl Ferguson was my neighbor right across the street. I always imagined it was his North Dakota roots that made him so economical in his oral communication. His work involved something to do with heating and cooling systems; it must have been on the engineering side of the business, not in sales. At the dinners our two families sometimes shared, or in neighborly interactions, a very few words from Earl went a long way. You could narrate a string of sentences to him about what you were up to lately, and he would nod his head in acknowledgement, cast a glance at your nearby pet and declare, “Keeko is a good dog.”

Did Earl Ferguson invite Special Agent Cook in to sit down? He must have done so, because he had an old-fashioned sense of politeness. I still remember the first time he wore blue jeans at the Thanksgiving table, and that was a big deal. Once they sat down, though, I am guessing it was not a lengthy conversation. Earl told the FBI on December 14, 1970, that I had always shown “the highest degree of moral standards. Mr. Ferguson advised that he has two children who have been close associates of DALE FINK…His loyalty and reputation are outstanding…he would favorably recommend Dale for any position with the federal government.”

On the very same day, the agent interviewed Peggy Toffolo, who lived right next door to the Fergusons. Her son Richard was in my grade but went to Catholic school until his final high school years; I barely saw him after going away to college, and their family did not spend social time with mine as did the Fergusons. (For a Retrospect story that centers on Richard and also includes Larry and Jim Ferguson, see “Richard to the Rescue.” https://www.myretrospect.com/stories/richard-to-the-rescue/) Peggy seemed always to be busy and stressed, even though she was a stay-at-home mom–either doing things with her four kids or working on various crafts and projects, such as sewing clothes and constructing really cool holiday displays. I can’t imagine she was eager to give a stranger in a coat-and-tie more than a few minutes of her precious time. Although she hadn’t seen much of me in the few years leading up to 1970, she attested that “Dale Fink has visited her residence on several occasions. She stated that she would favorably recommend Dale for a position of trust with the federal government. She did not have any knowledge of any derogatory information concerning Dale Fink or his family.”

In the next house down lived Marzelle Schwomeyer; the Special Agent in Charge evidently found her at home that same day (and, counter-intuitively, spelled her name correctly). She was about 20 years older than my parents or the Ferguson or Toffolo parents. She was a hardy and friendly woman with a small-town Indiana background who had lost her husband either before I was born or during my very early years. She gave me the first paying job I can remember: taking care of her dog Rusty while she went away on a trip for several days. I recall what a powerful sense of responsibility and wonderment I felt, at age nine or so, to be given the keys to enter her garage, then open the door into the kitchen, and replace the water and food in Rusty’s bowls, and let him run outside for a few minutes. I can still recapture the distinct, musty smell of her kitchen that was different from ours.

She led an active life for one who had become widowed at a relatively young age. I don’t think she was a lonely woman. I hope nevertheless that she appreciated the unexpected company for a little while on a Monday afternoon in December. Mrs. Schwomeyer apparently did not disclose to the SAC that she and I had once had a financial relationship. “Mrs. Schwomeyer stated that Mr. Irving Fink is her Legal Counsel. Dale Fink has visited [her] on numerous occasions and she stated he possesses a high moral character. During her discussions with Dale Fink, he expressed the opinion that he was definitely against the war in Vietnam and also appeared to be very liberal in his ideas…Mrs. Schwomeyer would recommend Dale for a position of trust with the government.”

There must have been a lot of people away from home that Monday, because the only other neighbor Mr. Cook visited was a man whose name I knew but who hardly knew me at all, who lived about six houses away. The only things I knew about him were that he worked in a factory and was a Democrat. My Dad was active in the Democratic Party, and I recall him saying that J. Engle was the only other registered Democrat on our street. Mr. Engle told SAC Cook that his “knowledge of Dale Fink was rather limited” but that he has “known of no derogatory information” and “he would recommend Dale Fink for a position with the government.”

The federal government position for which they were examining me was that of “sub carrier,” that is, a letter carrier who would be substituting for the permanently assigned carriers as they took days off or called in sick. The wage was $3.51 per hour. I had started the position in September, and I gather they were trying to vet me before the end of my probationary period. I believe they must have run a brief check on every new employee, but most of them were not converted to a “full field investigation.”

All the time I held my job that fall and winter, including while this investigation was taking place, I was clocking in at 4:30 am six days a week in order to make the very first postal run in Indianapolis, using a half-ton mail truck. The task was to deliver sacks of mail to the Governor’s office and the state Capitol building, so that staff in those locations could sort the mail before these public officials arrived to start their day. It was such a critical responsibility and at such an early hour that the backup plan if I were ever sick or unable to come in was not to call the boss, because there was no one on duty before 4:30 am. Instead, I was given the home phone number of the more experienced carrier who had trained me. I was to phone him by 3:30 am.

Once I turned in notice that I was resigning, there seemed to be an unjustified amount of hoop-la. A teletype memo was sent from Indianapolis not only to Boston but also to the Washington Field Office, and to New York City, Alexandria, Baltimore, and St. Louis, advising (yes, that word again) that “Dale Borman Fink officially gave his resignation effective Jan. eighth, next. Employee stated that he was intending to travel to California. Report follows.” Why did all those other offices need to know? I am without a hypothesis.

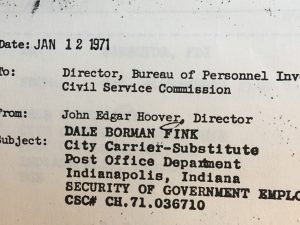

Even that much reviled personage, “John Edgar Hoover, Director,” piled on at the end. Under his name a memo went forth dated Jan. 12, 1971, addressing the Bureau of Personnel Investigations of the Civil Service Commission. It states in bold type that “captioned employee resigned his position effective January 8, 1971. In view of the above, no further investigation will be conducted.”

No further investigation was conducted. But hadn’t they done enough already? I regret the anxiety that any of those interviewed had to experience on my account—especially the people whose bond was simply living in the same neighborhood with my family and me. But without the FBI, where could I turn to find such a compendium of witnesses from different walks of life, who knew me at age 21, and who believed in me?

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Hey, Dale. I’m guessing that your neighbors’ testimonies as to your “high moral character” was a bit of a disappointment to these hard-working agents. They were probably looking for something a little juicier. Back in the ’70s had a few run-ins with the Bureau myself, both announced-as-such and not. I’ll tell you about them sometime.

I think I assumed when I received the files in 1979 that they were “out to get me” if they could as you suggest, Jim. But reading the files now at age 71, I am thinking maybe some of these agents were happy enough (this one anyway) to find out that a young man could be an antiwar activist and still have the respect of his neighbors and his employers and the admiration of his rabbi. Maybe the agent had a son in Viet Nam and he was hoping we could bring an end to the war and get him home safely. i’m still dreaming.

Dale, I’m sure there are fine people at the Bureau. I’m especially inclined to think so nowadays, grateful as I am to the Deep State, aka “the Rule of Law.” I ran into a less sympathetic and less law-abiding group back in the 1970s. I promise to tell the story soon.

Wow, Dale, that’s quite an investigation for a postal employee. Definitely attests to the paranoia and mindset of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. I agree with you that it’s a mystery that the agents talked with so many neighbors, but I love the way you describe what their interviews must have been like. Their personalities shine through. The only experience I’ve had that was even remotely like yours was about 15 years after your investigation, when I lived in a triplex in Sunnyvale, California, which was near a major Lockheed facility. Apparently one of the three young guys in the unit next to mine worked there and applied for a security clearance, and late one afternoon a uniformed woman knocked at my door and asked me questions about him, mostly if there had been any wild parties, which there hadn’t been. I assume he got the clearance, so no drama, and I’m sure no Hoover.

Brilliantly played! You take us through this whole major investigation, which surely must be for some high level job with a top security clearance . . . and then only near the end do we find out it is for a substitute letter carrier. Not even a full-time permanent letter carrier, just a substitute. Unbelievable! Surprised that your documented student radicalism didn’t disqualify you for the job. I guess all the witnesses who said you were trustworthy made up for it. Great story, Dale.

Thanks for commenting on the structure of the story–my decision to I withhold the nature of the secure federal position I was seeking. I was hoping that would add to the drama.

Wow Dale I didn’t realize we had such a radical guy in our midst! But the misspellings by all the agents investigating you doesn’t engender much confidence in our FBI.

And it’s counter-intuitive indeed that they got Mrs Schowomeyer right. Thanx for your fun story!

Worse than the misspellings, I thought, was the fact that they had a hard time determining if the Dale Fink at Harvard and involved in SDS was the same or a different person from the guy in Indianapolis! As mentioned, all it took was looking at my social security number. They talked about how “no one could connect the dots” after 9/11/2001 happened. By then, they had decades of practice in “not connecting the dots.”

Not a happy thought Dale!

But at least we know on your watch the mail came through!

Fascinating that the FBI would investigate a low-level postal employee so thoroughly, Dale, even if you had been a member of SDS. Seems like a huge waste of resources to me, but you do give us vivid descriptions of all the family friends and neighbors who testified on your behalf. I wonder if Louis DeJoy got nearly as much screening this year for the pleasure of royally screwing up our mail! Somehow, I doubt it.

I’ve had that same thought, Betsy, about someone like DeJoy! It was hard to believe the amount of time and correspondence going back and forth regarding someone who was ALREADY dropping off sacks every day at the Governor of Indiana’s office with no glitches. And why did they need to notify NYC and ST. Louis and those other places when I quit my job (I’m not sure I want to know)! BTW, I was also collecting mail from the mailbox in front of the Indianapolis FBI Building every day in one of my later runs.

Very interesting story. It makes me wonder if there is something in the FBI files about me.

In the spring of 1969 or the fall of 1970, I was walking up Garden Street across from Cambridge Common when I noticed a group of protestors marching and chanting “Smash ROTC, No Expansion” and similar statements outside Radcliffe Yard. I walked into one of the buildings in the Yard where most of the activity seemed to be located, climbed the stairs, and found myself in the Radcliffe President’s office, which had been occupied by the protestors. I looked around for a few seconds, and then walked back out and on up the street to the Radcliffe Quad.

That evening, back in Winthrop House, the phone rang in our room. My dad was on the line, furious at me. He asked me if I was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party, and whether my trip to Maine the previous weekend had been to attend a Communist Party rally. As it turned out, he was watching the news that evening, and they had a story about the takeover of the Radcliffe President’s office. They had picked out the most radical-looking person in the crowd of students, which, with my long hair and beard, happened to be me. My brothers yelled out “That’s Jeff!”

I assured Dad that I was not a card-carrying member of the Communist Party and that the trip to Maine was just to hang out with some friends at the beach. (I did not tell him about our ingestion of certain substances at said beach.) He then demanded that I get my hair cut. I pointed out to him that he was 800 miles away and could not force me to get my hair cut, and that ended the conversation.

After graduating, my draft number came up and I was called to an Army base in Columbus to take a physical. At one point, I was asked if I had ever advocated for the overthrow of the United States government, to which I replied “Yes, every four years.”

So I wonder what I might find if I filed a FOIA request for my own file, if it exists.

This is quite a tale, Dale. Amazing that the forces of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI were required for you to be a substitute letter carrier. Wonder how much investigations like these cost us taxpayers? At least you got excellent reviews!

Amazing story, Dale, even though I knew a fair bit about your activist past. To continue on the baseball theme of my own story, your story of interviews by the FBI — even involving J. Edgar himself — sure made mine about a summer legal position seem completely minor league.

Great details in the story. And we can all find humor in this now, with the benefit of time. But stilll…. And, like others, I was particularly amused by the way you withheld the position that you were being investigated for; I was assuming it had to be an ambassadorship at the least. That said, it might have been nice if the current Postmaster General had been subject to a bit more scrutiny before he was picked for this plum of a job.