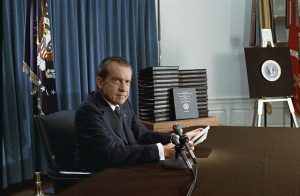

A surreal moment: My favorite photo of Richard Nixon. Public domain.

As psychology students, Patti and I spent the summer of 1974 in the U.K. working on a psychological research study in collaboration with a British Ob/Gyn named Katharina Dalton. Kitty, as she was called, was famous for first describing (and naming) premenstrual syndrome. Her preferred treatment for PMS was to administer the female hormone progesterone. In fact, it was her preferred treatment for almost everything, including depression and the pregnancy complication known as toxemia. She had prescribed progesterone to many of her own patients back in the ‘50s, resulting in a cohort of kids who had been exposed to it prenatally. They were now teenagers, and our task was to interview and test them—along with a control group whose mothers had not received the drug—and find out if and how it had affected them.

Nixon's address would go down at 3:00 in the morning, London time. But this was history and we were not going to miss it.

It was a great project and we loved interviewing the kids. (The mums always offered us tea and biscuits—that’s where we became tea rather than coffee drinkers—and we could hardly refuse, so we’d often have two or three servings a day.) The problem was getting to them, which turned out to be a slog. For some reason, Kitty booked a us flat in East Acton, a working-class suburb on the east side of London, while most of our subjects lived in or around Hampstead in the north. So each afternoon we’d walk ten minutes into East Acton, past the bank, the bakery, and the reeking butcher shop to the tube station, take the train into the city, transfer at Bond Street or Tottenham Court to a northbound train, and finally take a bus (or two) to wherever they lived—about an hour and a half each way. We ended up knowing London quite well below ground, but not nearly as well above. We passed the time reading or playing the word game Jotto until, incredibly, we both picked the same secret word: subway. (At that point we switched to Botticelli.) On weekends and days when we couldn’t arrange an interview, we made time to take in the sights: Parliament, Westminster, Windsor Castle, Hampton Court.

Meanwhile, the Watergate investigation was escalating. We both disdained President Nixon, so we had followed the events with relish bordering on glee, but at home it had seemed like an endless process. We think of it now as a series of revelatory bombshells—the White House tapes, the 18-minute gap, the Saturday Night Massacre—but at the time they trickled out like molasses. The Senate Watergate hearings—how quaint that Congress actually took its job seriously—were televised, but as they stretched to more than 300 hours you couldn’t watch them continuously and have a life. Patti called it the original reality TV. We would tune in occasionally (on the 14” color Sony my grandfather insisted on buying us for the exorbitant price of $399 when he first visited us after our marriage), but neither of us had time to really focus as the Senate committee called witness after witness. Erlichmann, Haldeman, Mitchell, Dean: It was hard to tell the players without a scorecard. We kept up by watching the 11:00 o’clock news and reading the San Francisco Chronicle the next morning. What did Nixon know and when did he know it? It was taking forever to find out.

In London, as the investigation built to a climax, it was even tougher to follow. Watergate was not topic A in the London papers and we had no TV in our flat. When we could find the International Herald Tribune, we’d read it on the train to keep current.

It took us five weeks—until the end of July—to interview all the study subjects in the London area. At that point we gave up our flat, hired a car, and braved left-side driving to find another half dozen subjects scattered across southern England. We stayed in a run-down B&B in Surrey with sagging floors and a single 40-watt bulb hanging from the ceiling, and a luxe country inn in the New Forest where we ached to spend a whole week. We subsisted on hearty English breakfasts and rich sweet-cream pastries that we picked up in bakeries in towns like Bagshot—the best English food we’d had on the trip. We visited Stonehenge, Salisbury Cathedral, and the old Roman baths at, well, Bath. And we largely lost track of Watergate.

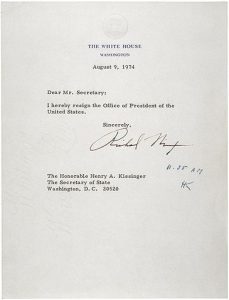

On returning to London we checked into a small hotel in Bloomsbury for a final week as tourists. And then the “Smoking Gun Tape” was released. The crisis accelerated, and a few days later, on August 8, we learned that Nixon would be giving a televised address, rumored to be his swan song. It would go down at 3:00 o’clock in the morning, London time.

This was history and we were not going to miss it. We set our alarm for 2:30 am. With no TV in the room, we pulled on our clothes and straggled down to the lobby. By 3:00, about twenty bleary guests, mostly Americans, had gathered in front of the telly.

The speech was short. We watched in groggy, relieved silence; no heckling or catcalls. But at the word resign, we all cheered and applauded. (Americans who travel abroad have a decidedly liberal bias.) Then we all returned to our rooms to sleep out the night.

We would complete the summer with two weeks in Ireland (where we interviewed two last subjects), France, and Sweden. It felt like a pall had lifted. Our long national nightmare, as President Ford put it, was finally over.

Until it wasn’t. Let the flashbacks begin.

John Unger Zussman is a creative and corporate storyteller and a co-founder of Retrospect.

I love your detailed description of the food and accommodations as you traveled the English countryside, and the interesting research you did (just this past weekend I was talking with a neonatologist at my brother’s birthday party who is hiring bio-geneticists. I asked him what they did and how that affected his work. He said they look at how, for example, progesterone affects the on-set of labor, which is a mystery in humans. Quite interesting, really.)

But being abroad kept you out of the Watergate loop, so interesting to hear how you learned about the impending resignation and got up early to hear the actual speech. These historic moments are worth getting up for. Let’s hope for another one soon!

Wonderful story, John! Your research sounds fascinating. These little fragments of your post-college life are part of the appeal of Retrospect. Love your account of getting up at 2:30 am to watch Nixon’s speech with other bleary Americans in London. And that picture of Nixon with Elvis. . . !