Everett Greene and Anita Hall, jazz vocalists

I was very excited to see Bob Hope perform his standup comedy during the opening of a new performance venue called Clowes Hall on the campus of Butler University in 1963. His opening sarcastic line has stuck with me: “It’s a great honor to be here at Clowes Hall…even though it is second night.”

A local jazz singer had called and asked if she might come and sing at Dad's bedside. Would he like that? And would it be all right if she brought along a male vocalist she had in mind?

A few years later, for my 17th birthday, I brought a date—Leslie, who had been part of a summer in France with me and 30 other Hoosiers–to that same venue to see the Lovin’ Spoonful and The Association. “Hot town, summer in the city. Back of my neck gettin’ dirty and gritty.” Pure eloquence.

A performance I found mesmerizing—that I attended solo at Symphony Hall in Boston when I was in my twenties–was the National Steel Symphony of Trinidad and Tobago, I had first encountered the celestial sounds of the steel drum on the Cambridge Common: just a few random West Indian guys having fun. It was amazing to see and hear what an entire orchestra could do with those instruments.

Jump to about 1988. An ex-girlfriend was in town. I wasn’t sure if we would be able to (or would dare) communicate very well or honestly, given the bitterness that had accompanied our breakup over 10 years earlier, the distance that had accrued between us and the fact she was now married and living in another state. I figured attending a show would be a good diversion; a friend told me that “Buster Poindexter and his Banshees of Blue” were going to be in town, at a local club near Central Square in Cambridge. My interactions with Mimi ended up being inconsequential and forgettable, but that concert—wow, it was unforgettable! Buster, the stage name of David Johansen, formerly of the New York Dolls, put on one of the most energetic and captivating performances I’ve ever seen, mixing funny narrative in between his songs.

When I think, however, about a performance that will remain in my mind and heart as the most memorable of all, it was not in a theatre or hall or club, nor in an outdoor space such as the Cambridge Common. It was not even a performance, according to one of the two principals, who corresponded with me as I was writing this piece. “No performance,” she said. “I was singing the light…bringing the same reverence as when I sing in church.” This memorable event took place in my Mom and Dad’s bedroom in 2015, two nights prior to Dad’s passing on Easter Sunday of that year.

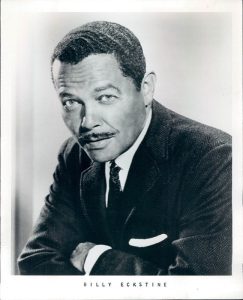

It was a Friday night, a very appropriate time on the weekly calendar for my parents to hear a jazz concert. They never stopped enjoying the musical genre that had captured the nation during their childhood and youth. Young Irv Fink had not only enjoyed the music but had taken up the clarinet as a kid, and then later the saxophone. He played the sax around the house when we were kids, and then for his 70th birthday, Mom got him a new clarinet, as he had decided to reclaim his chops on that instrument. The two of them continued listening to and acquiring albums (and then CDs) of Sarah Vaughan, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and Billy Eckstine.

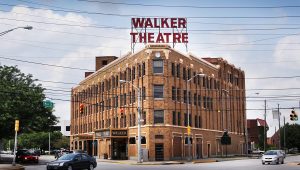

They had for many years attended concerts at the Walker Center in downtown Indianapolis, a venue named for and originally endowed by Madam CJ Walker, an Indianapolis woman who became the first self-made female millionaire in the USA, with her line of hair-care products designed with Black women in mind. Mom and Dad invited me to join them once, during my years in graduate school in Illinois in the 1990s. I saw their enjoyment of the music and the venue and noticed that they were among the few people there who were not African American. Yet they were not at all isolated; there were frequent and friendly interactions between them and other nearby patrons, some of whom clearly knew or recognized them. Some recognized them as regulars at “Jazz on the Avenue,” but occasionally someone would also recognize Irv Fink as their lawyer, even from several decades in the past.

On that Friday in April, my wife and son (aged 14) and I had flown to Indianapolis for the second time in two months, both in connection with my father’s decline.

In February, after being on a breathing tube, Dad had rallied and was able to be discharged and go home. We had arrived for that first visit during the time he was using the breathing tube. In the ICU when we arrived, he let us hug him gently, and then as he lay in his hospital bed he wrote a note, expressing appreciation for our having traveled to see him, and penned, “especially knowing that today is Jacob’s birthday.” As indeed it was! What a wonderful grandfather, to see past his own quite urgent troubles and acknowledge an important day in the life of a young adolescent. Later that day, Uncle Leon would take Jacob out for a birthday adventure–a Climbing Wall he had located.

By the time of our return in April, we no longer had the high hopes we carried in February, Dad was not having issues with breathing. But he had recently learned that he had rapidly spreading and previously undiagnosed bladder cancer to compound all the other problems he had faced for several months, He had resolved not to wait around for the cancer to spread further; he would bring his life to an end at a more rapid pace of his own choosing.

In a somewhat prophetic conversation with my sister Elaine the previous December, he had told her that he had experienced a remarkably high quality of life across nine decades and more. He had no interest in prolonging his life if at any point the quality was going to decline. At the time of that conversation, there was no reason to imagine he would be challenged any time soon by such dire problems. But now they had arrived. A few days before that Friday, he had let Elaine know that he wasn’t going to eat anymore. He called his sister and a number of other friends and relatives, to converse with them for one last time and say good-bye. During this period, Mom remained by his side and provided loving support and understood he was in his last days. She could not grasp all the details of what was happening, as her Parkinson’s disease had increasingly caused her to experience dementia.

On that Friday in April when we arrived, Dad was remaining in bed. He was growing weak on the fourth or fifth day of his fast. He had completed the phone calls. This man who could recite many lines of Shakespeare and all 80-plus lines of Rudyard Kipling’s “Gunga Din” from memory, and who could sing scores of songs of his own creation, was barely speaking anymore.

A local jazz singer, Anita Hall, had called Elaine and asked if she might come and sing at Irv’s bedside. Would he like that? And would it be all right if she brought along a male vocalist she had in mind someone who was also an admirer of our dad? Elaine checked with Dad and Mom, and they looked at each other and said yes. Anita’s mother, Delilah, had been one of Dad’s clients for more than a generation. Anita had grown up knowing of him not only as her mom’s lawyer but as someone who went to bat for all the right people. “Humanitarian, poet and good fight fighter,“ she called him in recent correspondence.

Before us, my siblings had arrived from Los Angeles, Cincinnati, and Germany, along with spouses and some of the grandkids. Anita showed up first, and the other vocalist arrived later and turned out to be Everett Greene—a regional legend in the jazz world whom my parents had heard perform many times. His voice has often been compared to that of Billy Eckstine. He is 88 as I write this narrative, and still touring, so he was 81 in April of 2015.

My sister ushered Anita and later Everett into the room, where Dad was lying alone on his side of the bed he shared with Mom. Mom, Elaine, my brother Leon and his wife Sue (and perhaps others) sat in chairs. Several of us stood inside the door and beyond, into the hallway, watching and listening to this private concert.

I don’t remember what songs they performed, but Anita tells me that one of the songs Everett sang was “Summer Time.” And also that when she sang, “The Impossible Dream,” Dad mouthed some of the words with her, and tears wetted his eyes. Elaine remembers that the two vocalists together sang, “When the Saints Go Marchin’ In,” and that several members of the family chimed in on some of the lyrics.

While writing this narrative, I have been listening to an interview that Everett Greene recorded with the Indianapolis NPR affiliate in 2016. His vocals are played throughout the interview, and each time I hear another one, I think, “That one sounds familiar. It must be one that he sang at Dad’s bedside.” I felt that way, for instance, in hearing Mr. Greene’s rendition of “Everything I have is yours,” a song recorded by both Billie Holiday and Billy Eckstine in the 1950s. I could easily imagine him singing it to Dad, knowing of Irv’s love for Bea, who was still there beside him after 69 years of marriage. Here is a YouTube clip of that song, from one of Greene’s albums. I know Dad would have loved the musicianship and embraced the spirit of this song.

The concert lasted well over a half-hour. When Anita and Everett finished and were saying good-bye, Dad was able to thank them effusively, pulling himself nearly fully upright in bed as he held out his hand. It was the most forceful gesture I saw him make in those final days, a powerful statement of the importance he placed on music and his admiration for those who performed it, even as his light was fading.

A boy discovers the rhythm and wonder of jazz and poetry and song and continues to derive pleasure from these sources throughout his long life of 95 years. Two talented people come to serenade him in the final days before he expires. Anita did not think of it as a performance. But what a glorious send off.

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Thank you Dale for sharing the unusual and incredibly moving story of the intimate jazz performance held for your dying father at his bedside.

I did have to smile however at your mention of Madam C J Walker. I was librarian at a vocational high school where cosmetology was among the trades we taught, and our library had many copies of Walker’s fascinating biography.

Glad to know the legend of Ms. Walker has spread far and wide. Maybe some day you can attend “Jazz on the Avenue.”

Thank you for sharing this poignant story, Dale. It is a true testament to your father’s love of jazz, his ability to connect with people and their admiration for him. It must have truly been something to witness, both the performance and your father’s strength at the end to rise up and thank these old friends for that wonderful send-off. Truly remarkable.

That’s an extraordinary–and extraordinarily moving–story, Dale. As a fellow jazz fan, I commend you on your choice (ahem) of parents; it’s important to keep the fan-line intact and thriving. (I suppose a classical-music fan who is the child of classical-music lovers could say the same thing. But that’s okay: music is music, etc.) The idea of having a couple of well-known jazz singers show up at the end is an occasion for joy, as your father clearly knew. We should all be so lucky.

Dale, the story you shared about your father’s final concert was the definition of a memorable performance for me. I know people in hospice care often respond to music when other things have shut down. I’m sure that concert brought your father much joy and comfort.

You’re right about music enduring to the end. The last time Dad was out of bed (the day before I got there), Elaine brought him to the living room because the cantor from our Reform synagogue came for a visit, and my sister was amazed as he sang her many of his own songs, especially the ones he wrote over the years for the Jewish holidays (much better songs than the ones they taught us in “sunday school”),

Your story brought tears to my eyes, Dale. A tribute to your father’s life, the power of music, and the dignity, sorrow, and joy of his passing.

What a happy-sad story. Your wonderful dad going out on his own terms, but the loss palpable. The concert sounds like the perfect thing he would enjoy, and what better way to celebrate the end of a long and worthy life. They say hearing is one of the senses that endures to the end, and the music gave him the strength to share his thanks. It gave you this great memory as well. Thanks for sharing it.

Beautiful.

You start out describing several concerts by performers we all might have seen, which were great. But then you move to that incredible final performance for your dying father by two talented people who had a personal connection to him. Wonderful that your whole family was there to hear it with him, and to see him pull himself up to thank them. Very moving!