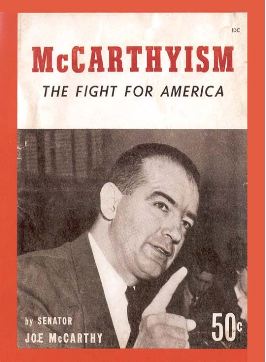

During the McCarthy Era, my old man was blacklisted for having been a member of the Communist Party. In the 1930s, the Communist Party stood as a platform for change. Joining the party ran parallel to my generation’s drive to join the Peace Corps or Students for a Democratic Society.

"Welcome to the American Dream, old man. Not so fast…"

Prior to the depression, my old man had earned a Merit Scholarship to M.I.T. for his boy-genius experiments in electronics. However, by that time, he was an orphan, taken sanctimoniously under the wing of the famous — or notorious, depending on your POV — Scripps family of newspaper fame.

“College is for sissies,” the Scripps Calvinists told my old man, then a lost and impressionable lad of 17. “You’re going to Seattle to learn the newspaper business from the ground up.”

So, my old man threw over the M.I.T. option for the Scripps family’s Horatio Alger bullshit and headed for Seattle. What the hell, he thought, I want to be a writer, too, and off he went. He was always a terrible strategist, my old man.

He lasted at the Seattle Scripps paper for about six months until he realized that the Scripps’ “ground up” had no ladder out. He jumped the Scripps ship and surfaced again as a teen radio operator on Japanese fishing boats that plied the waters of the Northwest in search of tuna.

The depression hit, and my old man never did get to M.I.T. Instead, he remained at sea, working his way through the merchant marine, sailing the oceans, taking better positions on larger ships as “Sparks,” the radio officer.

The depression hit, and my old man never did get to M.I.T. Instead, he remained at sea, working his way through the merchant marine, sailing the oceans, taking better positions on larger ships as “Sparks,” the radio officer.

In those lean days, my old man was glad for the officer’s salary but working conditions for most seamen were deplorable. My dad became a union organizer for the National Maritime Union and joined the Communist Party — until the Hitler-Stalin Pact divided them in 1939.

During the war, my father served in the merchant marine, making death-defying convoy runs on freighters, carrying war supplies to the Allies across the North Atlantic. He survived and went ashore for good in New York. Despite his lack of formal education, he was hired by a company doing early electronic experiments with sonar.

What does this have to do with money?

The war over, my old man and a buddy decided to start an electronic research and development company in what would become the Silicon Valley of the 1950s — Massachusetts’ own Route 128. My old man would supply the electronic genius while his pal, once crowned the world’s fastest typist, would raise the money and finesse the business end. So here comes the money part.

Problem was, all of the money for electronic r&d came in the form of government contracts and the government didn’t give out contracts to commies. From that moment out, making a living became a nerve-wracking scuffle for my old man, especially since he had spurned a university education.

By the early 1950s, he was making a no-guarantee living covertly attached to research funding at Boston University. Scientists in the biology department recognized his brilliance and ingenuity but the grants came and went. We were broke most of the time.

In addition to his lack of a college education and the Cold War blacklist, my father carried a third onus: clinical depression. Given the severity of his attacks, its remarkable he was able to function at all. He increasingly spent time away from us in the hospital, his disappearance always unannounced and only vaguely explained. My mother, although an independent woman and a radical herself, seemed oddly tongue-tied when my sister and I queried her about our father’s disappearances.

This perilous journey through The American Dream had an impact upon my own attitude toward money. By 12, I was working on nearby farms, baling hay, picking corn and digging potatoes, plucking apples in the crisp autumn air, high in the boughs above rolling Massachusetts hills. Beautiful memories.

This perilous journey through The American Dream had an impact upon my own attitude toward money. By 12, I was working on nearby farms, baling hay, picking corn and digging potatoes, plucking apples in the crisp autumn air, high in the boughs above rolling Massachusetts hills. Beautiful memories.

By 15, I was working in a machine shop, learning how to weld, run lathes, drill presses, and grinders. It didn’t seem like child labor. The machine shop was run by my pal’s dad. We built Serafina there. I got high on the whole production busy-ness, the sounds of machinery, banging, swearing, spitting.

Or I would work in tandem with a school pal on his parent’s farm. But there lay the difference: for these kids, farm chores and field labor were family responsibilities. For me…?

My parents were mystified: they certainly hadn’t ordered their kids to join the labor force. They knew what the struggle had been to end child labor. What, they asked, then did this work and its rock-bottom wages do for me? Was I saving for college at 12?

I couldn’t answer them. I had no idea why I was working and saving while other kids hung out at the beach. I continued working nights and Saturdays through most of my high school career.

My father never made it into the revolution, which he would have loved! He died at his own hand in 1964, months before the FDA approved lithium as an anti-depressant. Days earlier, he had also learned that decision makers in a large electronics corporation rejected a concerted effort by well-placed scientists to ease my father into the private sector.

This job would have — for the first time since the blacklist began in 1947 — given my father steady work with benefits and a salary commensurate with his talent, skills, and experience. Welcome to the American Dream, old man. Not so fast…

The turmoil of the 1960s turned all my poverty paranoia upside down. By 1967, everyone I knew was living on nothing — you don’t get paid to foment a revolution. And I learned that it’s easier to get through times of no money than to get through times of no dope.

The turmoil of the 1960s turned all my poverty paranoia upside down. By 1967, everyone I knew was living on nothing — you don’t get paid to foment a revolution. And I learned that it’s easier to get through times of no money than to get through times of no dope.

Decades later, I began to understand the roots of my adolescent labor obsession. By working as a kid, I had been dealing with the triple jeopardy of my old man’s health, education, and economic welfare. I had to prove I could take care of myself financially. For me, money was meant to be saved in a personal and political system that seemed perennially eager to deliver a rainy day.

Today, what I most value about money is my ability to give it away to others, but I’m getting pretty damned good at throwing some of what I have over myself, my friends, and loved ones. What the hell, there’s always something new to learn.

# # #

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

Charles,

I wonder if your father ever knew Emma Goldman and some of the other anarchists and communists of that time. I am so sorry that there was so little compassion for him. As usual, I enjoyed your rush of words whizzing by on the page.

Emma Goldman was quite a bit ahead of my father’s time, although she was a powerful influence until her death in 1940. Thanks for your observation: it sometimes seems as if the world had little room for communists or depressives, regardless of their intents.

A rich story of the roots of your attitude toward money. It also explains your empathy for and zeal to help the working man. I was sorry to read how your father died, a victim of the blacklist and the not-quite-in-the-nick-of-time arrival of suitable medication.

Thanks, John. The zeal for the working man is part of a larger class consciousness, largely imparted at dinner table conversations where my father — and mother — taught us much about history and politics with great humor, irony, and good company. We also had a lot of funny, articulate fellow travelers for family friends. It kinda soaks in.

Beautifully written, but oh so sad story of your father’s trials and tribulations, and their effect on you. Loved your transition to the turmoil of the late ’60s, and especially the lesson that “it’s easier to get through times of no money than to get through times of no dope.” After all of your history, you seem to have arrived at a current attitude toward money that sounds very healthy.

Thanks, Suzy. Oh so sad. However, this Retro post enabled me miss him; recalling my old man often finds me shadow boxing at my recollections.

Tough story told with compassion and zest, Chas. There is untreated mental illness in my family too, though it was my grandmother, who died before I was born, so I didn’t observe it first-hand. Your father sounds so brilliant, and so much a victim of circumstances and internal chemistry. You are his legacy.

Thanks for the good words, Betsy. And you’re spot-on: I am his legacy, as much to be admired as feared. And the circumstances — talk about a perfect storm of the personal (mental illness) and the political (the blacklist).

Hmmm….What a story, Hope my last comment was not out of line. You seemed to have learned a lot about life, in your family setting and I am sorry that your father suffered so much.

Your comment was not at all out of line, Rosie.