©Digger Archives

Baking Digger bread had only one stipulation — you had to give it away for free.

I graduated Harvard in 1967 and never looked back. The previous year, I had auditioned for the San Francisco Mime Troupe (pronounced ‘meem,’ not ‘myme’ — a long story in itself) and had been invited to join this wild radical theater company that performed free shows in the parks of the city.

Caught up in San Francisco’s free-city anarchy and resistance, seduced by its poets and folksingers and revolutionaries, I had been eager to turn my back on the red-brick traditions of Harvard. To hell with the diploma; I was gonna make radical theater.

The Mime Troupe’s director, R.G. Davis, a theater visionary with a penchant for rebellious thinking, got wind of my intentions. He kicked me down the stairs of the Troupe’s second-story studio and told me ‘don’t come back until you graduate.’ I thought it odd that the radical R.G. was so adamant about a college degree. Wasn’t this the ‘hip’ thing to do? I argued. Turn on, tune in, and drop out?

My question enraged R.G. That’s media bullshit, he growled. Drop out and you disappear. Turning on is irrelevant. Get high, don’t get high, just don’t forget to bring the ammunition. We commit, he continued. We engage. We breathe the fresh air of the parks and give free shows to the people. Drop out and you won’t be good for anything but smoking dope and playing guitars. We got plenty of that. We need thinkers. So get the hell out of here and learn how to think.

Can I come back after I graduate? I asked from the bottom of the stairs.

Yeah, yeah, Harvard, Davis replied. Come on back… next year. If there is one. Things were feeling pretty apocalyptic in those days, with napalm news clips coming back from Vietnam and American cities burning with uprising.

I finished my final year at Harvard, glowing with the expectation of joining the Troupe when I returned. I gave no thought to grad school or the draft. There was a war to stop and they could put me in jail before I’d kill farmers in a third-world country. Hell no. I was headed back to that rag-tag group of actors and poets, anarchists and carpenters, communists and comics who had set out to change the world with theater. A tough job, but somebody’s gotta do it.

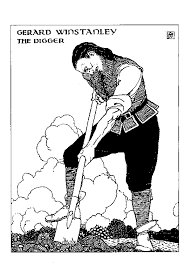

At the dawn of the vastly over-publicized Summer of Love, I trucked back to San Francisco in a rattling red GMC pickup that consumed more oil than gas. I rejoined the Troupe and landed in a Digger household in Diamond Heights. The Diggers were a loose collection of wanderers, free spirits, and anarchists who took their name from a movement in Cromwellian England. The English Diggers had believed in economic justice, an egalitarian contract with the flora and fauna of the planet, and open sexuality. The English Diggers lived largely in rural, utopian communes and developed a self-sustaining livelihood.

In the 1700s, the landed aristocracy descended upon the Diggers when the utopians “liberated” English common land originally granted to the underclass for grazing and gardening. As Europe collapsed and Guy Fawkes rose to prominence, the aristocracy clamped down on the poor. The Diggers were attacked and executed for their liberating behavior. Three hundred years before the Summer of Love, the English Diggers had opened the door for my San Francisco brothers and sisters to liberate San Francisco.

In the 1700s, the landed aristocracy descended upon the Diggers when the utopians “liberated” English common land originally granted to the underclass for grazing and gardening. As Europe collapsed and Guy Fawkes rose to prominence, the aristocracy clamped down on the poor. The Diggers were attacked and executed for their liberating behavior. Three hundred years before the Summer of Love, the English Diggers had opened the door for my San Francisco brothers and sisters to liberate San Francisco.

So the Diggers re-birthed themselves in San Francisco, this time in urban communes, largely in the Haight Ashbury. They had taken the name, spirit, and philosophy from their British forebears. The latter-day Diggers launched a contemporary assault on the bastions of private property, conventional thinking, and repressed libidos. Armed with the slogan “one percent free” they set out to create alternatives to the rules, regulations, and expectations of a big American city at the pinnacle — or nadir, if you will — of post-war hegemony.

As the ranks of dreamy hippies descended on San Francisco, the kids found that life was not as Timothy Leary or the Beatles had described. They descended by the tens of thousands and found themselves at the mercy of city and a culture that was simultaneously amazed by and terrified of the roaming youngsters who were looking for the Yellow Submarine.

In resistance to the still-expanding consumer culture, Diggers maintained they could create an alternative society that would depend on neither profit nor war. They set up a Free Store to distribute contributed clothing, blankets, appliances, and abandoned furniture. Need a change of clothes after escaping Kansas City? Head for the Free Store. They set up a Free Clinic, a coterie of Free Presses, helped spawn the Mime Troupe’s free shows in the parks and…

… the Diggers launched a Free Bakery.

Ecstatic with my post-graduate work, studying mime and movement, building shows from scratch, stomping on the boards of a commedia stage before a lawn full of laughing freaks, I lived happily on Mime Troupe wages — twenty-five dollars a week, raised by passing the hat after the show. The Troupe worked nonstop at the gritty warehouse studio leaving no time for a job and no money for food or clothing. No matter, I dropped by the Free Store to exchange one blue-jeaned, plaid-shirted uniform for another. I fought off several bouts of social disease thanks to the ministrations of the Free Clinic, and broke my bread free of charge in the Golden Gate Panhandle, thanks to the Digger Free Bakery.

The first Digger bakery began in the basement of a church on Waller Street. To make Digger bread for free, you need to scavenge free but healthy ingredients and tools. Baking bread for free took ingenuity and the Diggers were long on ingenuity. The church lent its ovens to the endeavor and Digger bakers hustled free whole wheat flour from a Hunters Point wholesaler who gave them damaged sacks. Whole wheat Digger bread broke the mold [sic]: at that time, whole wheat flour and organic foods were largely a thing of the future.

The most ingenious characteristic of Digger Bread was its shape. With no money to buy large baking pans — bakery brothers and sisters collected one- and two-pound coffee cans. They’d grease the cans with vegetable oil and mix flour and salt in warm water to nurture the yeast. The yeast they kept in cultures so they wouldn’t have to buy more. They’d add sugar, honey, molasses, anything sweet, even dried fruit that they collected on their early- morning runs to the city’s sprawling produce market.

The most ingenious characteristic of Digger Bread was its shape. With no money to buy large baking pans — bakery brothers and sisters collected one- and two-pound coffee cans. They’d grease the cans with vegetable oil and mix flour and salt in warm water to nurture the yeast. The yeast they kept in cultures so they wouldn’t have to buy more. They’d add sugar, honey, molasses, anything sweet, even dried fruit that they collected on their early- morning runs to the city’s sprawling produce market.

The wholesalers looked forward to visits from the Digger scavengers. They began to applaud the one-percent-free Digger mission. After all, the wholesale workers shared common purpose with the colorful diplomats from the Haight-Ashbury — to feed the hungry.

The market workers set aside fruits, vegetables, and grains that quietly dropped off the market’s loading docks and found themselves joining bubbling soups and stews in the cauldrons that Digger cooks brewed, lading out a bowl to anybody hungry, daily in the parks.

In the beginning, you had to slice the first Digger bread by hitting it with a hammer. Some folks claimed that Digger Bread could also be used to build retaining walls and walkways. Nonetheless, it was free and for many that meant sustenance where none other was to be had.

Gradually, the Digger bakers improved their technique and Digger bakeries opened up, six or seven of them around Northern California. Anyone could become a Digger baker. The only stipulation? You had to give it away.

In the spirit of their ingenious determination to create a free society, Diggers brought food to the Americas, those who had been spit from the belly of the beast and those who chose to walk away from the American Dream. Digger bread was tough, nourishing, went down warm, smelled of molasses, and it was one hundred percent free.

# # #

Charles Degelman has written two novels set in the anti-war and counterculture movements of the 1960s and ’70s. Both are available through the usual suspects.

Writer, editor, and educator based in Los Angeles. He's also played a lot of music. Degelman teaches writing at California State University, Los Angeles.

Degelman lives in the hills of Hollywood with his companion on the road of life, four cats, assorted dogs, and a coterie of communard brothers and sisters.

Your story evokes not only memories of those times but the feel of them. I had heard of the Diggers but didn’t really know who they were or what they did, let alone their 18th-century provenance. Why was their slogan “1% Free?” It sounds like the bread and the clinics were 100% free.

Thanks for your response re: Diggers and ‘Digger Bread.’ Regarding 1% Free… In response to the growing rip-off of San Francisco’s utopian ‘Free City’ culture via head shops, poster stores, hippie clothing and gear warehouses, the Diggers began a 1% Free campaign to convince the new merchants to contribute 1% of their profits to SF’s utopian free stores, clinic, bakery. The sticker imprinted with the two characters from Chinatown’s tong societies advocated for the 1% Free movement and was posted in the windows of participating merchants.

That was really fascinating about the original Diggers. Thanks. I had forgotten about the movement of free stuff. In my town we had a Jesus Free Store for a while and a food co-op that lasted much longer. It must have been a blast to be in that theater troupe, really exhilarating. Are you glad that guy sent you back to Harvard to complete the degree?

Thanks for reading, Constance. I’m glad you enjoyed the story. I was glad I returned to Harvard for my final year although I didn’t use my diploma for decades. After graduating I jumped right back into the radical theater scene that mushroomed in San Francisco in the late 60s. And the hits just kept coming.

I finally dragged out the diploma to land my first steady job 25 years later when I took a job as a writer, editor for a non-profit educational organization. And of course, on my re-entry into academia, only recently, my diploma served me very well, thanks.

Most important, I was glad I finished Harvard… mission accomplished. If you’d like to read more about that time, see my two ‘resistance’ novels, Gates of Eden (set in the anti-war movement) and A Bowl Full of Nails, set in the radical utiopian counterculture as represented in “Digger Bread” and my newer contribution to Retrospect, “Can’t Bust ‘Ems.”

Really enjoyed reading this. I also knew only vaguely about the Diggers, and was happy to learn more. I will definitely look for your novels, Charles.

Regardless of our paths, degrees of separation often converged during those times. It became an expectation, rather than a surprise, a good thing. How did you know of the Diggers. I’m guessing I knew who you knew ;-). That was the way, then. Were you ever at Black Bear, on Lost Coast, California?

Loved this, Charles! You capture the idealism, laced with astonishment and ingenuity, of that unique time in SF. It made me yearn for those times when 100% free was a noble goal.

Delighted to hear you are/were a fellow traveller!