This prompt led me back to several dark caves.

My sometimes vigilant parents rushed to the television button a couple of beats too late to protect me from this grim portal on life and death.

Starting with my earliest television memory, of a bundled family of Hungarian refugees crossing to freedom over a rickety suspension bridge during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, being shot dead by Russian soldiers. The family crumpled in a pile, including dead children who reminded me of myself. My sometimes vigilant parents rushed to the television button a couple of beats too late to protect me from this grim portal on life and death. As seen on The Today Show, with Dave Garroway. “Peace” he used to sign off with.

Which led me to google for a photograph of this Hungarian bridge-crossing. I found raw scenes (see below) from the short-lived Hungarian Revolution (a democratic uprising against Soviet control, which was crushed in a few days by the overwhelming might of the Russian army, suggestive of current Russian intentions toward Ukraine, suggestive of how tribes have settled scores since the beginning), but no photograph found of the aborted bridge-crossing.

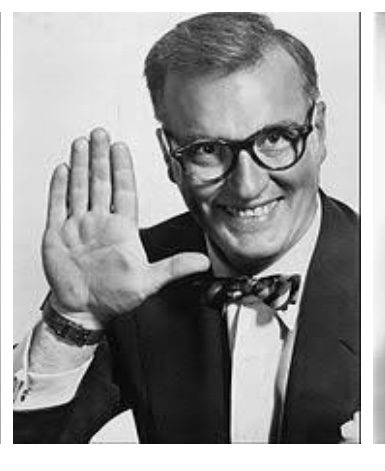

I did find photographs of Dave Garroway. I chose one of these, of Dave making his “Peace” sign, for my featured image. His remains a familiar and reassuring face after all these years. An icon from my childhood. I also read what I already knew, that Dave shot himself to death in 1982. As recited in Wikipedia, “His easygoing and relaxing style belied a lifelong battle with depression.”

The peaceful surface belies the underlying turmoil. Hmmm. I try to remember what they taught me about history in grammar school. They inserted “under God” into the Pledge of Allegiance. They praised the Indians for their cooperation in making Thanksgiving such a successful holiday. We studied the Middle Ages, and I got to thinking how crappy it would have been to be a serf in the Middle Ages, with all those la-di-da lords and ladies living large, with the power to make me eat dirt if it so pleased them. Where can I go for refuge?

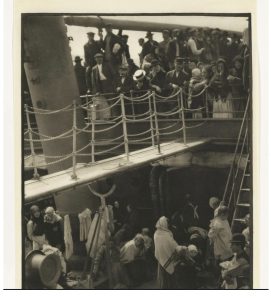

There is a famous 1907 photograph by Alfred Stieglitz, titled “The Steerage” (see below). There are several prints of it on museum walls around the world. I saw it at the Whitney Museum of American Art. It shows people crowded together on two decks. At first glance it looks like these are people arriving to America for refuge (under the banner of New York harbor’s Statue of Liberty, and the stirring words of Emma Lazarus, “…Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free…”). But the story line digresses. The people huddled in the photograph are returning to Europe from America. That fact gave me pause as I studied the photograph. The text writers come up with various positive spins for why the people are returning home, but for me there is the hollow feeling that America failed them. No refuge here.

Indeed, there wasn’t much refuge here for a lot of people following the Immigration Act of 1924 which established a national origins quota system. I don’t remember much grammar school class time spent studying this national origins quota system.

One final (for now) dark cave of my acquaintance. I’ve been told that on average it takes an immigrant family three generations to adjust to the new place, with reactive emotional strains and fissures impeding, distracting, and defeating the process from the first step off the gangplank. I don’t have an explanation for poor results after the third generation.

Here is what I said about myself on the back page of my 2020 humor/drama/politico novel "The Debutante (and the Bomb Factory)" (edited here, for clarity):

"Jonathan Canter Is a retIred attorney; widower; devoted father and grandfather (sounds like my obit); lifelong resident of Greater Boston; graduate of Harvard College (where he was an editor of The Harvard Lampoon); fan of waves and wolves; sporadic writer of dry and sometimes dark humor (see "Lucky Leonardo" (Sourcebooks, 2004), funny to the edge of tears); gamesman (see "A Crapshooter’s Companion"(2019), existential thriller and life manual); and part-time student of various ephemeral things."

The Deb and Lucky are available on Amazon. The Crapshooter is available by request to the author in exchange for a dinner invitation.

You have beautifully expressed our schizophrenic approach to immigration, Jon. I was struck by your final paragraph about the three-generation adjustment, since my grandparents were immigrants/refugees, depending on how that’s defined, and I’ve felt somewhat “different” from people whose ancestors have been here longer.

Marian,

Thank you for your positive response to my story. Immigration often confronts the haves against the have nots. And justice is generally is the eye of the beholder. As to the three generation filtration equation, it seems to take time to adapt, and to come to terms with what is left behind in the country of origin. The historic beauty of America has been a begrudging willingness (sometimes with pitchforks) to incorporate newcomers, but I sense that willingness is in shorter supply these days.

Thanx Jonathan for reminding us of the inconvenient truths and the dark chapters in the history of our so-called civilized world..

And how do parents – like your sometimes vigilant pair – explain to their kids the TV footage from Ukraine?

In retrospect, I might have been better prepared for launching into the world had I lived in a more transparent cocoon in my formative stages. And seen more, and expressed more. I think, for example, awareness of mortality (taking a bite from the Tree of Truth, or was it the Tree of Life, or whichever was taboo at the time) struck me where I lived, and might have been assuaged by some external assistance..

Wow, Jon, seeing that Hungarian bridge scene on television must have been traumatic. Unless your parents were able to convince you that it was just a TV drama. After all, we grew up watching people killed on TV all the time, and knew it was make-believe.

Thank you for showing me “The Steerage.” I have been researching it ever since I read your story, trying to find a positive interpretation. I think you are right that America failed them, probably by turning them away at Ellis Island. You should read Marian’s story “Bypassing Ellis Island,” which she wrote in 2017 on the Immigrants prompt.

The spin on the Stieg is that some returnees were skilled craftsmen who had done what they could to elevate American barbarism (an ailment common to high falluting elephants 🐘), and chose to return to an aesthetic environment better able and inclined to appreciate their skills; and others were returning to pick up their share of the family jewels which their duchess grandmother was distributing at that time; and still others enjoyed the briny salt air of an ocean voyage.

I do remember the Hungarian refugees coming here and knew they were fleeing repression, but was thankfully spared the details you saw of television. During WWII, Jewish refugees fleeing the Holocaust were sent back to die. We had our quotas by then. For a long time, many in our country have feared “the other.” Our unwillingness to help refugees fleeing for their lives continues at our southern border.

I consider the news clip I saw on TV of Hungarian refugees shot not as a trauma to me, but as an eye opener. My “sometimes vigilant” parents may, in retrospect, have misdirected their vigilance. Better to have protected me from the shock and violence of Disney animation and Barbar (dead mothers, orphaned animals) than from the grim truths of the real world (mortality, immorality, impermanence, plus dead mothers and orphaned animals).

Dark caves indeed, Jon. You describe them well. I even recognized the cheery face of Dave Garroway even before I read your story, and, of course, the contrast with the Hungarian bridge-crossing and the steerage ocean-crossing is indeed enormous and unsettling. Thank you for reminding us of the very much darker sides of immigration.

You also reminded me of my own observations on TV of the Hungarian revolution, probably also by watching the Today Show. And then it was briefly brought to reality because a Hungarian professor and his family were temporarily housed in the home of a Yale professor who lived in our town and the two sons, my age and my brother’s age, were enrolled in our school for several weeks. They barely spoke English — and, of course, seven and nine-year old American kids certainly didn’t speak any Hungarian — but I remember the message imparted not only on my brother and me but a lot of our classmates:: “Just be kind to them.” I think we were, and they moved shortly to New York when there father got a position at Columbia, but I can still recall the incredibly sad — indeed, shellshocked — look on both boys’ faces almost the entire time they were in our school.

John, I appreciate your comments. Looking backwards—looking retrospectively—reminds us of many sweet and good things, but it is important I think to stay in touch w things we would sooner forget,like the Russians crushing the Hungarian Revolution, so that we might try to learn from history and improve the future.

The history of immigration is deeply emotional, for the trials, failures, and successes all. If you have never been to the Ellis Island exhibit, it is worth a visit, as it spells out the history of immigration to the US, including the poor treatment of the successive waves, and the changing demographics over time. You would think that, with so many people having experienced the traumas of immigration in their own families, that we would be more welcoming to others. When we can be kind, always good to take the opportunity. In terms of being protected from seeing evil in the world, in Disney movies or newsreels, that is a deep subject. Children need to learn the truth but also how to be resilient, and that is not so easy.

I would like to visit Ellis Island. As to protecting children from seeing evil, I agree, that is a deep subject.

Your parent’s reaction reminded me of my father, who would suddenly remember that he needed something in another room and send me to fetch it whenever a Tampax commercial came on the TV. despite their never being a mention in the ad on what the product actually was.

But typically, violence was considered just fine for kids.

I can see how a European with a skill set that could earn a good living there would go back, considering the myriad bad aspects of American culture. Sad how badly returning to Europe in the 20s rebounded on so many people starting in around 1933.

Thank you, Jonathan. (Poor Dave Garroway, I didn’t know.)

I’ve known several people who came to the U.S. after the Hungarian Revolution. Your story brings up memories of them, so thank you.

I don’t think that returning to one’s homeland necessarily signals a failure on the part of the States or any other host country…I know of several migrants from South America who saved enough money to return and live in prosperity with or near their families. Homesickness is a thing, ahe pace of life in America perhaps may not be to everyone’s taste. I’ve had trouble just adjusting to life in different parts of the U.S.!

Yes, returning to one’s homeland may have many explanations, as many as there are for leaving one’s homeland in the first place. As I look at the Stieglitz photo, however, I feel sadness for those who invested so much of themselves in coming to America, and then turn around. Perhaps some of this sadness is due to the wisdom of hindsight, that so many people in Europe, including those who returned there, suffered bad fates in mid 20th century, while so many (certainly not all) of those who came to America and stayed, flourished.

I, too, recognized Dave Garroway, but did not know he had committed suicide, Jon. The rest of your story is profound and unsettling. Laurie references the Jews trying to escape Nazi Germany, but were turned away. They were on the St. Louis and that tale is horrifying and legendary. Ken Burns will share another of his epic documentaries in the autumn, this one covering the Holocaust (he previewed it at the end of “Ben Franklin” a few weeks ago; he said it was the most difficult but important piece he’s ever done).

Your examples, from the Russians putting down the Hungarian revolt, to the Stieglitz photograph, remind us of the harshness with which the spirit of freedom is often met.

Harshness abounds. Amazing (call it a miracle) that the “spirit of freedom” still flickers.