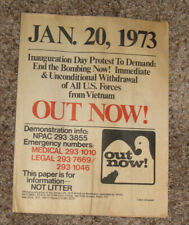

How did people manage to meet up, amidst a crowd of 100,000 protesters, in an era without cellphones? That is perhaps what amazes me the most as I think back almost a half-century to my participation in the huge demonstration against Richard Nixon’s second Inauguration on January 20, 1973. I had arrived on one of dozens of buses that departed Cambridge and Boston, along with my friend Claudio. My sister Elaine traveled in a two-car caravan from Ann Arbor, Michigan. Our brother Leon and his companion Sue (not yet my sister-in-law) drove from New York City. We were all part of a gigantic land-based flotilla composed mostly of hundreds of charter buses coming from all over the East Coast and the Midwest.

The night before the Inauguration, as we awaited the midnight bus to DC, my friend Nancy and I hung around Loretta Lynn’s private bus outside Boston’s Symphony Hall–and finally got to tell her we were fans and thought she was a great feminist.

I marvel at the significance of having an elected official there to register his dissent against a sitting President from his own party.

How did we find each other? We spoke on our landlines the day before, selected an intersection and a time, and crossed our fingers. If we missed that connection, there was no backup plan, except—keep your eyes open and hope to find one another!

The departure schedules for the buses for all those marches on Washington—and for many of the drivers of cars as well—were determined by working backwards. You wanted to be proximate to the Mall where the speeches and rallies would take place between 8:00 and 9:00 am, which would give you at least an hour to get yourself to a bathroom, find some coffee, yogurt, and donuts (non-Jewish establishments had not yet discovered bagels), get your legs moving a bit, and locate a convenient spot to be sedentary for the next several hours. The musicians and folksingers who warmed up the crowd usually started about 10:00 am. Working backwards from the desired arrival time and building in one gas/snack/bathroom stop along the way meant leaving either Ann Arbor or Cambridge/Boston around midnight.

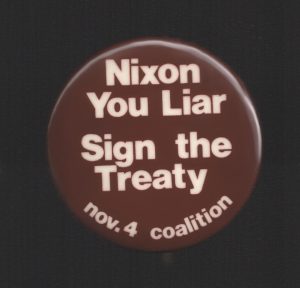

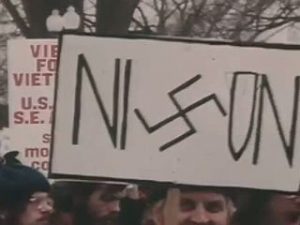

Why did so many Americans regard four more years of Richard Nixon as an abomination? One could point to almost any of his domestic or foreign policy decisions in his first term, including his efforts to overturn the legacy of the Earl Warren-led Supreme Court and to bring it under the leadership of right-wing, corporate-friendly ideologues (i.e., Lewis Powell, Warren Burger). Two of his nominees for the highest court were so blatant in their ethical lapses as well as their espousal of racial segregation that they were rejected by the U.S. Senate. But the freshest source of outrage at that time of the second Inauguration was the “Christmas bombing” of North Vietnam, The peace negotiations to end the Vietnam War were being conducted in Paris (with the government of South Vietnam, the government of North Vietnam, the United States and the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam at the table) and were all but concluded. In the effort to squeeze just a little more from the Vietnamese, Nixon and his henchman Henry Kissinger decided to “carpet-bomb” the North, just one last time. According to a 2012 BBC article (https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20719382), the “Christmas bombing” lasted from Dec. 18 to 29th, with a pause on Christmas Day. The first night’s sortie encompassed 129 B-52s, each carrying tons of explosives. Over the course of those ten days, there were 729 sorties. As an example of the level of destruction, a single sortie destroyed about 2000 homes in Kham Thien, a heavily populated Hanoi shopping district.

The result of all that? Besides forcing the population to live in the underground bunkers they had been building, thousands more Vietnamese civilians were killed, and a couple dozen more American pilots were shot down and captured. About ten days after the Inauguration, Nixon and Kissinger would announce they were signing the treaty—agreeing to the very same terms they could have had before unleashing this final demonstration of their unbounded inhumanity.

Claudio had enjoyed meeting my whole family when they all attended our Commencement the previous June of 1972. My family was readily able to find us in the procession to the outdoor Tercentenary Theatre, where the degrees were conferred, by watching for the large banner we carried as we walked along in our coats-and-ties, opting to forego the caps and gowns. The banner was a large white sheet painted with the words, “US OUT OF VIETNAM/ HARVARD OUT OF AFRICA.”

The reference to Africa on our banner stemmed from protests led by African-American students during the spring of 1972. Harvard was a major investor in Gulf Oil stock; Gulf was one of the main beneficiaries of the continuing Portuguese dictatorship in Angola. The student demand was to “Divest” from all holdings that helped to prop up companies that profited from continued African colonization. There were anti-colonial movements at that time in all the Portuguese colonies—Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau and the Cape Verde Islands. Ironically, or perhaps karmically, a group of junior Portuguese officers, veterans of the Africa wars, would start an Armed Forces Movement just a couple of years later and become the vehicle to overthrow their country’s dictatorship in 1975. The newly installed democratic government would quickly grant independence to all three colonies.

Claudio and one or two of my other friends had joined my family at dinner after Commencement at Durgin Park, a famous restaurant located in a dingy area of Boston that would blossom a few years later as the Quincy Market/Faneuil Hall redevelopment. It was famous for its slabs of roast beef that extended beyond the diameter of the plate and for its impatient and demanding waitresses who would just as soon tell you where to get off as take your order. Sadly, the redevelopment and the influx of suburban customers led eventually to the demise of the iconic restaurant.

Knowing the approximate time we would expect to arrive in DC, we set our meeting for a couple of hours later. How we selected a location, I have no recollection! It wasn’t based on examining Google Maps: the Internet was not yet even a glimmer in the military’s imagination.

Claudio and I found the designated intersection, but not with a great deal of time to spare. I was urgently in need of a bathroom, so I left him there, hopeful that he would recognize Elaine. (Leon and Sue were going to arrive later and become part of a different meetup plan.) After a few minutes of wandering, I felt fortunate to find an eatery that had a sign near the entrance pointing to basement-level restrooms. I imagined the restrooms were supposed to be for customers only, so I was happy that I could just follow the sign and slip down the stairs without having to justify my presence to any staff.

What a relief! I relaxed in my stall, until I heard the puzzling and unexpected voice of an older man, asking “can I help you out, there?”. Wait—was that voice speaking to me? Oh, man, he was up on his tiptoes and looking at me over the top of the next stall! He seemed too old to be menacing, but seated as I was on a toilet, I felt that I was in a vulnerable position. “I don’t need any help,” I said, hoping to sound a bit gruff but not wishing to start a fight. As I completed my business, he was no longer visible but still talking. “How big was it?” I ignored that, went to wash my hands without even looking around, and got out of there as efficiently as I could.

When I made my way back to the designated corner, Elaine and a couple of her friends and Claudio had found each other—the plan had worked! Naturally, I had to tell them about the unwanted encounter I had just experienced. When I contacted my sister while writing this essay, the first and strongest memory she unearthed of our entire time at the Nixon counter-inaugural was of that experience. Same for me! Most of the other details have drifted away.

Bread & Puppet Theater from Vermont, a constant presence at antiwar marches. A banner reads ‘Nixon’s the #1 war criminal.’ (Photo by David Fenton/Getty Images)

Since I’ve brought you this far into the adventure, however, I can share with you the words of one of the most eloquent speakers that day. Pete McCloskey was a Marine Corps veteran and Republican member of the House of Representatives from San Mateo County, California. He had run a quixotic campaign in the GOP primaries against Nixon, and apparently decided our event was more meaningful than the official “coronation.” It would end up being the Watergate burglary and cover-up that forced Nixon to resign two years later. But the deep anger against Nixon was grounded much more in his war crimes and crimes against humanity than in his overzealous efforts to disrupt and dispatch his political foes.

I don’t remember if I heard his words that day. But listening to a recording I found on the Web, I marvel at the significance of having an elected official there to register his dissent against a sitting President from his own party. In one part of the speech, he calls out an honor roll of those who have stood up to oppose the war: Senators Wayne Morse and Ernest Gruening (of Oregon and Alaska), the only votes against the Tonkin Gulf Resolution; Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers from his perch at the Rand Corporation; Ron Ridenhour, a soldier who disclosed what he heard about the My Lai massacre and kept it from being covered up; brothers Daniel and Philip Berrigan, Catholic priests who did so much to organize against the war.

Here is a later excerpt:

“We have to bow our heads in shame that it took a single man’s tragic decision, the 12-day Christmas carpet bombing, to finally awaken the conscience of a nation. But it’s happened.

“We meet today to do a far higher thing than to inaugurate a President. We meet to exercise a constitutional right, and I think a constitutional duty for the privilege of being an American, to peaceably assemble and for a petition for redress of grievance. We meet at a time of reflection on past insensitivity, regret over the time it has taken us to change national policy, shame over the ways that our science and technology and industry have been translated into killing and destruction, but also a quiet pride that what is best in each of us—faith and love and compassion—may at long last become the policy of a nation.”

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

Great story, Dale. It brought back a lot of memories and how upset we all were with the bombing and Nixon getting a second term. I well remember Pete McCloskey, having moved to the Bay Area just the year before these events. Hard to imagine we had some Republicans with conscience!

Fun story, Dale, and I’m sorry I missed that demonstration. I had just started a job with the federal government, but in Cambridge, not D.C., so I couldn’t manage to get there. And yes, how we found people in huge crowds before the days of cell phones is something I think about frequently.

Thanx Dale, we could sure use a few Republican legislators with some moral fiber like Pete McCloskey now.

When will we ever learn.

Thanks for sharing your memories of protesting Nixon’s second inauguration, Dale. This really transported me back in time to how many of us felt back then. Also loved the reference to Durgin-Park. We were lucky to have the experience of eating there when our son was at Harvard, although the rudeness was a bit of a shock to our midwestern sensibilities..

Thanks for this counter-inauguration narrative, Dale. At least Nixon had his comeuppance and resigned in shame. Reading McCloskey’s words, it is hard to imagine that a Republican said those – speaking of love and compassion. As Goldwater’s granddaughter put forth in the pages of the Washington Post recently, he’d be drummed out of the party today.

For my inauguration story, I decided to think outside the box. But you thought inside the stall — even more creative. And your story is a good reminder that not all preidential inaugurations were as uplifting as the one we all just witnessed.

McCloskey’s words are truly memorable. And I also recall listening to a speech by Wayne Morse at Yale Law School when I was in high school and being similarly moved.

Your pre-cell rendezvous concerns also remind me of similar ones during the 1970 March on Washington. But I think our plan then was either to stick together through everything or just see you afterwards at the apartment where we were all staying.

Thanks for a great retelling of that time. Sometimes we get so caught up in the travesties of today, we forget how truly horrible the past was. It affected all of us and where our lives went I think. Your story of meeting up reminded me of when I was a freshman and made plans to meet friends at Times Square on New Year’s Eve–which didn’t go as planned, but things worked out somehow.