You might think that when people become refugees from their own homes, are living in an improvised encampment, and focused on day-to-day survival, then “manners” would be the first thing to go. But that definitely was not true among the people of “La Po’lvora.” There, on the outskirts of the small city of Antigua, in the central highlands of Guatemala, after the destruction of most of the dwellings in town by an earthquake, I encountered some of the most polite children I have ever met in my life. And standing behind their every move and courtesy were their remarkably polite and gracious parents and extended families.

The people of "La Po’lvora," and especially the children, will always remain in my heart and mind as exemplars of the utmost courtesy and compassion in a time of dire need. They showed us something much deeper than just “good manners.”

Po’lvora means “gunpowder” in Spanish. I have not been able to figure out—even now, researching on the Internet–why the large meadow on the outskirts of Antigua carried that name. It was where the largest number of city residents relocated in the immediate aftermath of the earthquake of February 4, 1976. The quake measured 7.5 on the Richter scale; it would kill 23,000 and injure another 77,000. It covered a large area of the country and damaged most of the roads, so people weren’t thinking of traveling to another town to take shelter; they instead hurriedly made plans to sleep outdoors, wherever that was safe and feasible.

My sister Elaine, her boyfriend Bob (now her husband of over 40 years) and I had come to Antigua to study Spanish and to travel around. After collecting information through the mail, we had chosen a school called La Escuela de Lila (Lila’s School). For a very reasonable fee, we received seven hours a day of one-on-one Spanish instruction plus three daily meals and a room in someone’s private home. I was 25 at the time and was assigned to work with a long-haired and vivacious teacher named Celia (pronounced Say-lee-uh), who was about 20. The very first lesson involved her asking me, “Le gusta el coca-cola?” And I had to practice replying both “Si, me gusta el coca-cola” and also, “No me gusta el coca-cola.” It wasn’t lost on me that the language was being introduced using a North American corporate icon, even though much of the suffering of the people of Guatemala could be attributed to Yanqui imperialism. Nevertheless, I was enthralled with Celia’s lessons and I pushed those thoughts aside in order to be a diligent and devoted student.

The head of the household in which I stayed was a well-off businessman involved in the production and export of honey. Bob and Elaine were in a different home; they had preceded me by several weeks. As a result, they started out and remained considerably ahead of me in their ability to speak and understand Spanish.

In the aftermath of the earthquake, the city’s inhabitants pitched improvised tents in any area free of built structures. Everyone recognized right away that the structures that remained wholly or partially standing might come tumbling down suddenly—and many did–due to the unpredictable temblores (aftershocks) which continued for several days. Families identified every green space available to set up their temporary quarters. This included even the pretty park with a fountain in the city center where, before the terremoto, amidst the hustle and bustle of nearby tiendas (stores), the shoeshine boys, around 9 to 12 years old, used to hang around seeking customers, bearing their brushes and cloths, spray bottles, and tins of polish.

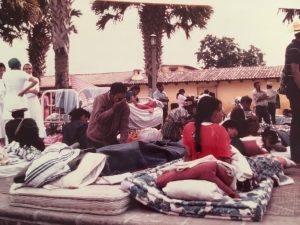

People dispersed in all directions, but the largest concentration of displaced residents from Antigua headed uphill and towards the mountains, to the large green meadow that everyone called “La Po’lvora.” Almost none of them had actual tents: they fashioned their living and sleeping quarters from bedcoverings, tablecloths, and burlap sacks propped up on sticks, poles, or pieces of lumber. Many of them were designed to accommodate upwards of six or seven family members. I never got a look inside one of them, but I did not see evidence of any of the Guatemalans rolling or unrolling sleeping bags. Most likely, they had brought bedsheets and blankets from their homes.

Except for us, all those seeking shelter on La Pol’vora were Guatemalans. Any North Americans or other tourists that were around (and we had seen a good number of them in previous weeks) seemed to have high-tailed it out of the country pretty quickly, as soon as the disaster struck. We heard later that many had contacted the American embassy for help in finding flights and returning safely home. For better or for worse, we had planned this trip for a long time and making an early exit never crossed our minds. (I’m not saying that was a good thing! Our parents, I’m sure, wished we had been a bit less intrepid in our commitment to continue our adventures.)

Unlike everyone else on La Po’lvora, we had nothing out of which to fashion a tent. We had not packed one, because this was not a camping trip. Furthermore, we knew it was not going to be the rainy season. Instead, we had high-quality sleeping bags from Eastern Mountain Sports or comparable outlets, which we could roll up neatly into compact and colorful stuff sacks. On the grounds amidst the dozens of tents, one could easily spot the nylon surface of one brown, one blue, and one orange sleeping bag.

We had slept out in the open once before when we rented a cabana in Iztapa, a beach town on the Pacific Coast. We left our belongings in the cabana and opted to lay our sleeping bags directly on the sand. But there we were not visible to anyone else, under the stars on a black-sand beach, watching the breakers with their amazing bioluminescence. In fact, the beach in Iztapa is where we were sleeping when the earthquake struck in the wee hours of the morning on February 4th. We went back to sleep for a couple of hours, and then on awakening, found out that everyone was speaking of nothing but the earthquake, and trying to find out how much destruction It had caused. We even met one long-haired American man who claimed that, since he had seen fire the day before (there had been some kind of large fire visible from the beach) and that was followed by an earthquake, that there must be a third strike coming. “If I see lava, man, I’m running for the sea,” were his apocalyptic and memorable words.

We realized our safest refuge would be back in Antigua—because at least we were familiar with the environs, and knew a few people, such as those associated with Lila’s School. And anyway, we had planned to return to Antigua after our beach trip, before plotting the remainder of our travels. It just happened that our last day in school had been Friday, Feb. 2nd; we headed off on Friday afternoon for our weekend on the beach, and then the earthquake struck on a Sunday. Travelling back from Iztapa to Antigua by bus required a change of buses in Guatemala City. The driver was getting reports from his dispatcher as we traveled and announcing what he learned to the passengers: twenty dead, thirty-five dead, fifty dead. No one could yet imagine the thousands who were in the process of perishing.

Knowing that 50 to 100 people had died, we realized, “this will make it into the news back home…we had better find a way to reassure our families.” We waited in a long line for at least two hours in the capital at one of the main post offices in order to send a telegram home to North America. We had plenty of time while waiting in line to craft the words for our message, prioritizing brevity, since we would be charged for each character. We got it down to five words (plus a period): “All’s well STOP Call the Finks” was the message we telegraphed to Bob’s parents. The two sets of parents had met one another and there was no reason to pay for two telegrams, right? (“Wrong,” would have definitely been the response of the Fink parents!)

It didn’t occur to us how much nervousness our parents would experience in trying to decipher and parse meaning from our pared-down wording. “Suppose one of them is in the hospital but recovering? They wouldn’t want us to be alarmed so they probably would still write ‘all is well,’ right?” In other words, for any member of a future generation reading this: a national calamity is not the time to be miserly with your words or your wallets. Give your family a full update of what is going on!

Bob was a medical student at the time. He volunteered to help with patients at the hospital in central Antigua, all of whom had been moved outdoors.

Once arrived back in Antigua, we were assuming we would stay at a pension, just as we had planned before the unexpected quake. There were three of them in town and they all had reasonable prices. We quickly learned, however, that two of them had been destroyed and when we went to get a room at the other one, we learned that although it was intact, it was closed due to possible structural damage—and fear of los temblores. I am not sure how we found out that the place to go, now that, like the rest of the city, we had no place to live, was to La Po’lvora. No doubt it was from conversations that Elaine had, because her Spanish fluency, built on the foundation of her previous French fluency, had advanced well beyond that of Bob or of my mere one week of Celia’s instruction.

Guatemalans—mostly the men–were making numerous round trips from their homes to La Po’lvora, to retrieve items to be saved from further damage and to make it possible to live for a few days outdoors. We had the benefit—if you want to think of it that way—of being able to carry all our possessions in a single trip in our backpacks.

We found an unoccupied patch of grass about 20 feet away from other people’s living quarters and put down our backpacks and sleeping bags in their colorful cases on La Po’lvora.

We were a community, for those few days, of at least a few hundred people. We witnessed very few idle hands. From way before sunrise, women were getting up before the other members of their families to make fires from wood, and then making tortillas. Not “making tortillas” the way I do it, opening a package from the store and heating them over the flame on my gas range; I mean they were mixing up corn flour (masa harina) and water, forming them into a circular shape, and baking them on some kind of griddle over the wood fires that they had just built.

The men were carting materials from their homes back to La Po’lvora, and they were also going back into their homes from the first day to begin making repairs. This was tricky, with the temblores, but they had to make the homes habitable so that their families wouldn’t have to sleep outdoors more than a week or so. We were still able to go into town and purchase produce and other food supplies from some of the outlets, and even to order simple meals at outdoor tables. On these expeditions, we saw how hard everyone was working. We also realized that for the first time, we could get a glimpse of the nicer homes in the city. Normally, they were completely hidden behind high walls and courtyards, but the earthquake had toppled nearly all the walls and left the houses visible to any passerby.

There were public health and medical activities taking place as well. On our second day on La Po’lvora, a municipal official made an announcement over a loudspeaker system, informing us that all of us were required to line up and get a typhoid shot, since we may be drinking contaminated water, or consuming food made using contaminated water. This was slightly terrifying. The idea of people lining up by the hundreds to receive inoculations from people that weren’t their own doctors? That sounded like something you see on a news report from a Third World country during a disaster. Wait a minute; we were in a Third World country during a disaster, and we were the gringos who had not contacted the U.S. embassy and requested help in getting out of there.

Fortunately, Bob already had his typhoid shot—perhaps because he was in medical school at the time in Chicago, where he and Elaine lived. In any case, it was only Elaine and I who had to line up for the shots, which left Bob free to play lookout. This turned out to be helpful. Closely observing the line, Bob determined that the doctors and nurses administering the shots were using the same needle for a certain standardized number of patients, then opening a brand-new syringe. He counted the people in front of us and then escorted us to a spot in line where his algorithm predicted that she and I would get the benefit of a clean needle. He was right on target.

What about the amazing politeness and graciousness that I referenced in the opening paragraph of this narrative? It was on display all the time, among everyone who interacted with us. But my most vivid memory is of our mornings. Keep in mind that we three North Americans were shrouded in darkness under the stars during the night. But as soon as the sun rose (and it rose quite early) anyone who was up could spot us in our brown, blue, and orange bags on the ground. As soon as any one of us opened our eyes, we discovered that several children in the age range of four to eight were standing respectfully about 12 to 15 feet away and watching for us to stir. As soon as one of us did, they would say, in a chorus of sweet young voices, one after the other, with smiles on their faces, “Como amaneciste?”

I had learned to say “buenos dias” for good morning or good day. But Elaine knew that the verb “amanacer” meant “to wake up.” Therefore these kids were asking, literally, “how did you wake up?” This was obviously another morning greeting that we hadn’t learned, equivalent in other cultures to asking “how did you sleep,” or just another way of saying “good morning.”

Once we had experienced this the first morning, I kept my eyes partially closed the next time I was about to awaken, and was able to discern that a small line of kids was once again standing there, just waiting for their opportunity to greet us. They seemed like the most courteous children in the world.

Once we received and reciprocated their greeting, what happened next was also part of their amazing manners. They ran back, 50 or 100 feet away, to a tent belonging to their family, and returned to give us coffee in metal cups. They did not ask how we liked our coffee; they served it black with lots of sugar. One of the mornings, they also brought us tortillas with black beans to go with our coffee.

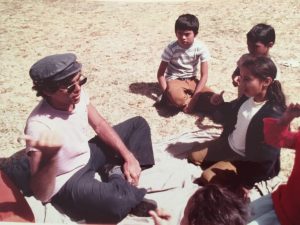

Author teaching songs with movements to some of the children. He had been working as a full-time day care teacher at the time.

The parents and extended families were the source of this international and cross-cultural good will. They were the ones encouraging the children to make the gringos feel welcome and a little less hungry. They would accept our smiles, waves, and nodding heads from a distance, but did not feel as comfortable or confident as the children in approaching us directly.

The people of La Po’lvora, and especially the children, will always remain in my heart and mind as exemplars of the utmost courtesy and compassion in a time of dire need. They showed us something much deeper than just “good manners.”

Dale Borman Fink retired in 2020 from Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, MA, where he taught courses related to research methods, early childhood education, special education, and children’s literature. Prior to that he was involved in childcare, after-school care, and support for the families of children with disabilities. Among his books are Making a Place for Kids with Disabilities (2000) Control the Climate, Not the Children: Discipline in School Age Care (1995), and a children’s book, Mr. Silver and Mrs. Gold (1980). In 2018, he edited a volume of his father's recollections, called SHOPKEEPER'S SON.

A terrific tale, Dale. I love the detail of your narrative, and I especially love the ultimate finding embodied in those children. I subscribe to the notion that compassion, real compassion, exhibits itself in demonstrations of grace under pressure. Clearly that happened here.

Amazing post, Dale! The detail that you included here, as well as the pictures, makes it easy to envision the situation that you experienced. I visited Antigua in (about?) 1980, so have some sense of the physical and social situation there, though your situation was much more “on the ground” than mine (visiting a graduate school friend who was working for Agua del Pueblo).

Thank you Dale for sharing the tale of the potentially dangerous yet awe-inspiring Guatemalan experience you shared with your sister and future brother-in-law.

And once again it’s heartwarming to see your affinity for children!

It is so moving that children who had very little, and then nothing at all after the disaster, were so well mannered and friendly. Their culture obviously valued kindness to the stranger in their midst, something many of us have sadly forgotten these days.

This was really interesting, and a well-told story–I could picture it all so well. It is a bit amazing that you just headed back to Antigua given the situation, but as a result you experienced a community pulling together to help each other out–much more than simply the week of Spanish school and trip to the beach. What a gift. Those who have little are often the most generous. The pictures were wonderful too. Thanks for sharing everything.